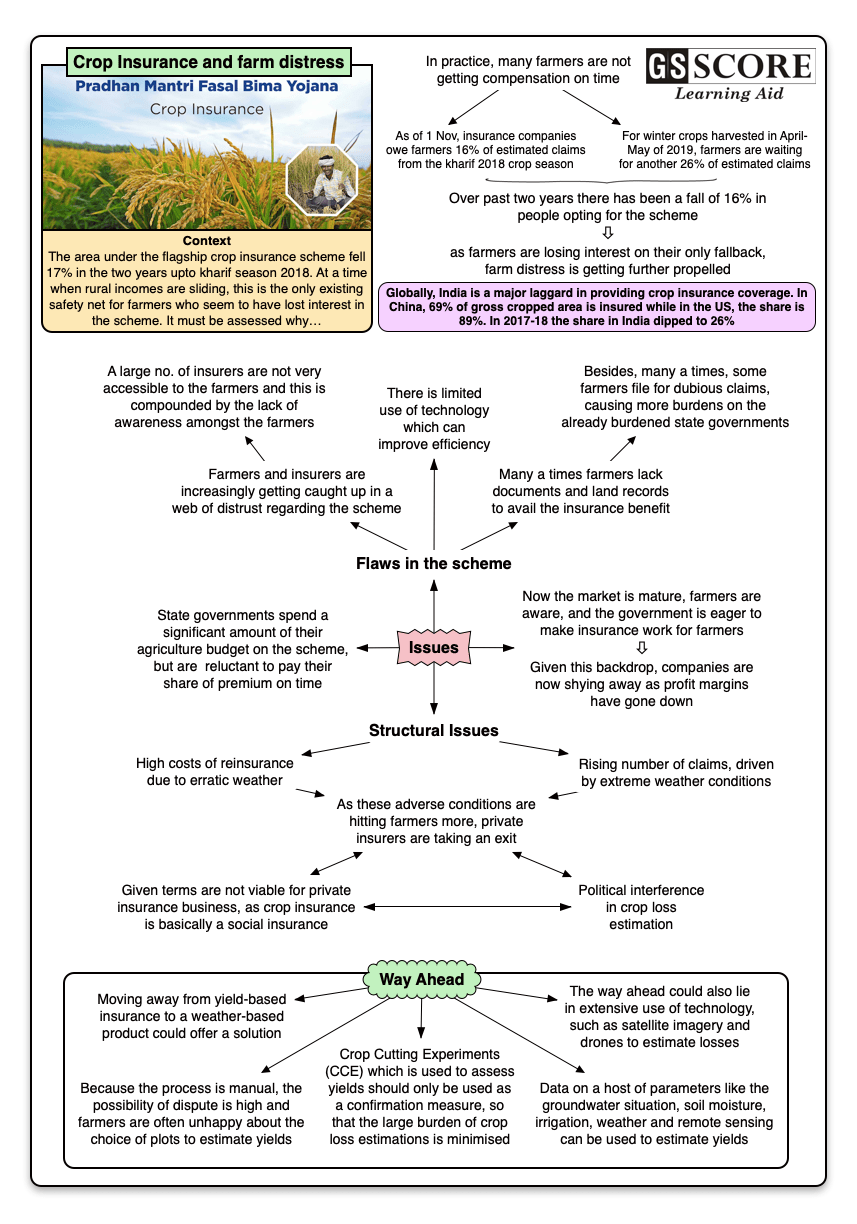

The area under the flagship crop insurance scheme fell 17% in the two years upto kharif season 2018. At a time when rural incomes are sliding, this is the only existing safety net for farmers who seem to have lost interest in the scheme. It must be assessed why.

Issue

Context

The area under the flagship crop insurance scheme fell 17% in the two years upto kharif season 2018. At a time when rural incomes are sliding, this is the only existing safety net for farmers who seem to have lost interest in the scheme. It must be assessed why.

Background:

- The Pradhan Mantri Fasal Bima Yojana (PMFBY) was launched in June 2016, and since then it has cost nearly ?1 trillion in premiums.

- But the scheme has over time shown many flaws. Over past two years there has been a fall of 16% in people opting for the scheme. And as farmers are losing interest on their only fallback, farm distress is getting further propelled.

- Theory of the Scheme: Any farmer who avails a loan will simultaneously sign up for insurance; any crop damage will be evaluated by state government officials; and the insurer would eventually pay out a compensation amount commensurate to the degree of yield loss.

- In practise, few farmers get compensation on time:

- According to estimates, as on 1 November, insurance companies owe farmers 16% of estimated claims from the kharif 2018 crop season.

- For winter crops harvested in April-May of 2019, farmers are waiting for another 26% of estimated claims.

- Many states are suffering crop losses due to heavy rains this year. In Maharashtra alone, an estimated 10 million farmers are affected. Farmer organizations are now demanding that the state be declared hit by a “wet-drought".

- Drought, for the lack of rainfall in the early months of monsoon (June-July), and wet since crops like soya bean, cotton and onion were washed away by three weeks of continuous rains in October.

- Globally, India is a major laggard in providing crop insurance coverage. In China, 69% of gross cropped area is insured while in the US, the share is 89%. In 2017-18 the share in India dipped to 26%.

Analysis

How did the farmers enlist in crop insurance?

- Many farmers got themselves covered under the crop insurance scheme without even being aware.

- Premiums were automatically deducted from their crop loan accounts held by public sector banks (without their consent).

- However, the insurance seemed like a blessing in case of any calamity; for example, in the case of flooding in Bihar by an overflowing Kosi river, where much of the paddy crop got washed away.

- But settlement of such claims is a distant reality for many farmers.

What are the issues that farmers face?

- The insurers are mostly private firms who do not have a local office. This makes it difficult for the farmers to reach out to them, and mostly it is through the banks from which they took their loans.

- Most insured farmers have no knowledge about whom to report their losses to. They do not have any details about the insurance policy, which crop was insured, or the amount of coverage (sum insured).

- The helplines of the private insurers’ do not work most of the time, and when they do; the customer executives seldom follow the local language of the farmers.

- There has also been report of cases where a private bank sold mortgage insurance to a Telangana farmer who was made to believe it was crop insurance.

- Most insurers expect farmers to intimate them within 48 hours of crop damage. But in reality, 48 hours of a calamity are critical for farmers and such an outreach to the insurer is not feasible or possible. For example, in case of Kosi flooding in Bihar, most farmers reported their homes being under water for the first 48 hours.

Flaws in the scheme

- There is limited use of technology which can improve efficiency.

- The scheme is gaping with implementation challenges.

- There is limited evidence of success of the scheme.

- Farmers and insurers are increasingly getting caught up in a web of distrust regarding the scheme.

- Many a times farmers lack documents and land records to avail the insurance benefit.

Structural Issues:

- Private exit: Lately, four private insurers did not bid for insurance clusters in the kharif 2019 crop season. As adverse weather conditions are hitting farmers more, private insurers are taking an exit. Insurance industry is also facing a slew of problems which is forcing them to exit:

- High costs of reinsurance due to erratic weather

- Rising number of claims, driven by extreme weather conditions

- Political interference in crop loss estimation

- Given terms are not viable for private insurance business, as crop insurance is basically a social insurance.

- State government reluctance: Under the crop insurance scheme, farmers pay only 2% of the premium while rest is borne equally by the Centre and state governments. State governments spend a significant amount of their agriculture budget on the scheme, but are reeling under the following issues:

- They are reluctant to pay their share of premium on time.

- There are examples like the Madhya Pradesh government limiting the maximum pay-out. To lower its financial outgo due to premiums, the state government reduced the sum assured by 25% from an earlier 100%.

- What was built as an element of protection into the scheme - state governments determining the extent of damage – has now become one of the main reasons for long delays in compensation.

- The extent of estimations to be completed within a limited time frame is also an issue. Currently more than seven million crop loss assessments are to be done every year.

- To fill in the gap left behind by private firms, public sector insurers now account for 65% of the crop insurance market. They are burdened by claims of crop loss due to heavy rains witnessed in 2019.

- It is possible that public insurers, too, may express intent to exit, unless the government covers their losses.

- Maturing Market: Until recently insurance companies had decent profit margins. This was because of the unique nature of the scheme which kept costs low by selling policies through the banking network and crop loss assessments which were mostly carried out by state governments. The heavily subsidized scheme had a lot of value for insurers.

- Now the market is mature, farmers are aware, and the government is eager to make insurance work for farmers. Given this backdrop, companies are now shying away as profit margins have gone down. Insurance companies cannot be entrusted with the scheme where so much public money is flowing.

- In order to maximise profits, insurance companies opt for various methods like:

- Choosing low-risk profitable clusters.

- Forming cartels in order to quote higher premiums during bidding.

- And finally exiting, if nothing works.

- Farmer exploitation: There is also the issue of farmers exploiting loopholes in the scheme. Many times they file for dubious claims, causing more burdens on the already burdened state governments.

Solutions to fill in the lacunae in crop insurance scheme

- Because the process is manual, the possibility of dispute is high and farmers are often unhappy about the choice of plots to estimate yields. Moving away from yield-based insurance to a weather-based product could offer a solution.

- The way ahead could also lie in extensive use of technology, such as satellite imagery and drones to estimate losses, which PMFBY has been slow to implement.

- Data on a host of parameters like the groundwater situation, soil moisture, irrigation, weather and remote sensing can be used to estimate yields.

- Crop Cutting Experiments (CCE) which is used to assess yields should only be used as a confirmation measure, so that the large burden of crop loss estimations is minimised. New technologies can be adopted for this purpose.

Conclusion

Between 1985 and 2012-13, the reach of India’s crop insurance schemes was modest. PMFBY made some progress in addressing in reducing insurance premiums and expanding the insurance coverage to include more crops and risk factors faced by farmers. However, the scheme remains behind its own target. One of the major bottlenecks in accessing PMFBY is that farmers lack documents and land records to avail insurance. Also, compensation is often delayed, inadequate, and even denied. All these result in farmers facing a severe fund shortage to start their next cycle of crops. As droughts become more frequent with climate change, the concerns in better implementation of the scheme need to be addressed at the earliest.

Learning Aid