Context

The World Economic Forum with its report, Dashboard for a New Economy Towards a New Compass for the Post-COVID Recovery, which outlines a framework for macroeconomic metrics that could fill the gaps currently left by GDP has attempted to provide a metric that looks beyond a nation’s income and considers welfare, the environment and people.

Background

- Economic growth has raised living standards around the world. However, modern economies have lost sight of the fact that the standard metric of economic growth, gross domestic product (GDP), merely measures the size of a nation’s economy and doesn’t reflect a nation’s welfare.

- GDP’s blanket use for gauging a nation’s welfare has been questioned on many occasions, even by its inventor, the US economist Simon Kuznets.

Analysis

What is GDP?

- Gross domestic product (GDP) by definition, is the total monetary or market value of all the finished goods and services produced within a country’s borders in a specific time period.

- As a broad measure of overall domestic production, it functions as a comprehensive scorecard of a given country’s economic health.

- GDP can be calculated in three ways, using expenditures, production, or incomes. It can be adjusted for inflation and population to provide deeper insights.

How GDP falls short?

- GDP by definition is an aggregate measure that includes the value of goods and services produced in an economy over a certain period of time. There is no scope for the positive or negative effects created in the process of production and development.

- For example, GDP takes a positive count of the cars we produce but does not account for the emissions they generate; it adds the value of the sugar-laced beverages we sell but fails to subtract the health problems they cause; it includes the value of building new cities but does not discount for the vital forests they replace.

- Environmental degradation is a significant externality that the measure of GDP has failed to reflect. The production of more goods adds to an economy’s GDP irrespective of the environmental damage suffered because of it. So, according to GDP, a country like India is considered to be on the growth path, even though Delhi’s winters are increasingly filled with smog and Bengaluru’s lakes are more prone to fires.

- GDP also fails to capture the distribution of income across society – something that is becoming more pertinent in today’s world with rising inequality levels in the developed and developing world alike. It cannot differentiate between an unequal and an egalitarian society if they have similar economic sizes.

- Another aspect of modern economies that makes GDP anachronistic is its disproportionate focus on what is produced. Today’s societies are increasingly driven by the growing service economy – from the grocery shopping on Amazon to the cabs booked on Ola. As the quality of experience is superseding relentless production, the notion of GDP is quickly falling out of place.

- We live in a world where social media delivers troves of information and entertainment at no price at all, the value for which cannot be encapsulated by simplistic figures. Our measure of economic growth and development also needs to adapt to these changes in order to give a more accurate picture of the modern economy.

- Modern economies need a better measure of welfare that takes these externalities into account to obtain a truer reflection of development. Broadening the scope of assessment to include externalities would help in creating a policy focus on addressing them.

- Recent years have seen several extensive and rigorous efforts to identify relevant elements of well-being and tackle different dimensions of the measurement question. These include the UNDP’s Human Development Index (1990-2020); the comprehensive review of well-being dimensions by Stiglitz, Sen and Fitoussi (2009); the OECD’s Better Life project (2018, 2020); the Bennett Institute’s Wealth Economy Project (2019); the Recoupling Dashboard (2019); and the World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Index (1979-2019), Inclusive Development Index (2015, 2017) and Social Mobility Index (2020).

Proposal of the World Economic Forum

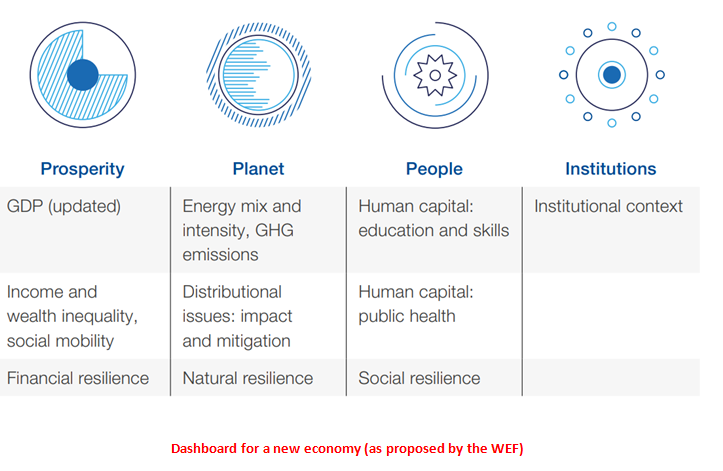

- In its new report, the Forum has proposed a scorecard made up of four dimensions that need to be brought into balance: prosperity, the planet, people and the role of institutions.

- The Forum’s ‘Prosperity’ metric includes aspects such as social mobility, income inequality and financial resilience. GDP still features within the Prosperity dimension, but updated to reflect different dynamics within the world economy.

- In high-income economies, it has to track the slowing economic growth, its impact on standards of living and an increasingly unequal income distribution with a view to facilitating effective policy countermeasures. Whereas, in emerging markets, the metric needs to account for those countries’ more evenly spread growth, which has contributed to ending poverty for millions to date.

Dashboard for a new economy (as proposed by the WEF)

- This metric weaves together the evolving energy mix and, by association, the development of greenhouse gas emissions. It also accounts for the cost of climate change and its mitigation – for example through carbon taxes.

- Human capital is the key determinator for the dashboard’s ‘People’ dimension. It incorporates metrics for tracking education and re-skilling to guide government spending toward transforming workforce skill-sets and avoiding job losses as the economy’s structural transformation continues to unfold.

- The final dimension is ‘Institutions’, with the Forum pointing to a decline in institutional quality, as evidenced by negative trends around press freedom, judicial independence and budget transparency, etc.

Finding the right balance

- While each of these four dimensions already carries inherent complexity, their interconnectedness creates further difficulties, and trade-offs will need to be made to ensure adequate balance.

- While governments may introduce a carbon tax to help abate climate change, they need to consider the impact this may have on jobs, economic and social polarization, for example.

Conclusion

- Finding a new globally acceptable tool to measure the ups and downs of our economic activity will remain a challenge – but one that must be tackled urgently to ensure the world’s economic recovery is on the right course.

- As a step in this direction, India is also beginning to focus on the ease of living of its citizens. Ease of living is the next step in the development strategy for India, following the push towards ease of doing business that the country has achieved over the last few years. The Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs has developed the Ease of Living Index to measure quality of life of its citizens across Indian cities, as well as economic ability and sustainability.