The country did successfully build 100 million toilets, but this success must be made sustainable

Issue

Context

The country did successfully build 100 million toilets, but this success must be made sustainable

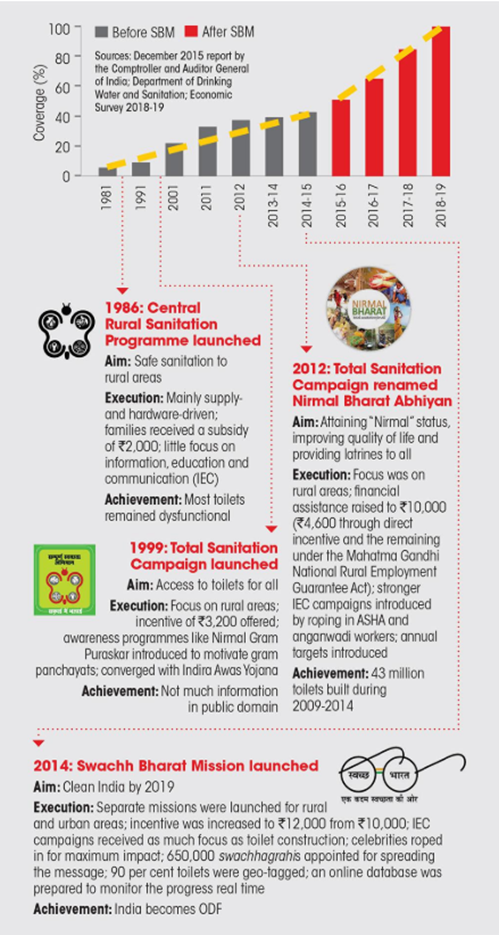

Background

- In the past four years, India has built 100 million toilets in about 0.6 million villages and another 6.3 million in cities.

- The country has been declared open defecation free (ODF) — a seemingly impossible task just some years ago.

- According to government estimates, by February 2019, over 93 per cent of the country’s rural households had access to toilets; over 96 per cent of them also used the toilets, suggesting an important change in behaviour.

- 99 per cent of the toilets were found to be well maintained, hygienic and in 100 per cent of these toilets, excreta was “safely” disposed — there was no pollution and, in fact, in 95 per cent of the villages, there was no stagnant water, no wastewater and only minimal litter.

Analysis

Current scenario

- Let’s be clear that slippages happen in all programmes. So, even if toilets are built and people have started using these, the trend can reverse in no time.

- In many districts of Uttar Pradesh an earlier laggard state there were people, particularly women, who were using toilets and wanted more.

- But in Haryana, declared ODF, people were slipping back to the old habit of open defecation; this is when it had invested in changing the behaviour of people.

- There is the issue of excreta disposal. NARSS 2018-19 uses an inadequate and erroneous definition of “safe” it defines safe disposal if the toilet is connected to a septic tank with a soak pit, single or double leach pit, or to a drain.

- There is the issue of credibility of assessments crucial to know that we are on track. At present, all the studies are commissioned by the project funders or the proponent ministries.

Swachh Bharat Mission: An outstanding achievement, but challenges remain

- Including people who still lack toilets, overcoming partial toilet use and retrofitting sustainably unsafe toilets are some of the massive tasks ahead

- The Swachh Bharat Mission-Gramin (SBM-G) was a remarkable programme. Nowhere, has there been a rural sanitation programme that has combined political priority with resources on such a big scale.

- The Mission faced the pressure of reporting both toilet coverage and behavioural change.

- The massive task is to include people who still lack toilets, overcome partial toilet use, and retrofit toilets which are not yet sustainably safe.

- There is a time bomb of rural and small town faecal sludge management as tanks and single pits fill up and are difficult to empty. But solid and liquid waste management is now receiving the much deserved attention. Children’s faeces and hand washing are in the frontier.

- Methodologies evolved like the national Swachhathon to crowd source innovations; Rapid Action Learning Workshops for lateral sharing of experiences, immersive research for ground truthing; and now CLNOB (Community Leave No One Behind) to facilitate communities to reach and support those behind people with disabilities, the old and infirm, the very poor and weak, migrants, marginalised, and others.

Haryana still defiant

- Class division seems to be derailing Swachh Bharat Mission’s (SBM) efforts in Haryana, which was declared open-defecation free (ODF) way back in 2017 and has seen a massive campaign to sensitise people.

- Problem of land to build a toilet and so the panchayat asked to use the community toilet at the village chaupal. But people from higher castes do not like people from lower castes using it.

- These community toilets are usually located about a kilometre from the houses and who would go so far every day is the question.

- Then there are those who have been left out of this toilet construction exercise and have no option but to defecate in the open.

Nilgiris sets example of community effort

- Toilets, whether mobile or in households, were a rarity till the launch of Swachh Bharat Mission (SBM), in Tamil Nadu's mountainous Nilgiris district, tucked away in the Western Ghats.

- About 72 per cent of the households in this Tamil Nadu district lacked access to toilets due to lack of knowledge, adaptation and cultural constraints

- Under previous sanitation programmes, community toilets were set up, but failed due to lack of maintenance. Most villages are scattered across the hills and are surrounded by tea and coffee plantations.

- Chances of getting attacked by a wild boar or an elephant while defecating in the open are high in such regions. So, communities came forward for individual toilets when the government offered an incentive of Rs 12,000 per household under SBM.

- Over 100,000 tribals, dalits and women formed self-help groups and raised a loan of Rs 20 crore to build toilets.

- The struggle has now instilled in the communities a new sense of judicious use of water.

Water shortage drives people in Marathwada to open fields

- Maharashtra’s rain-shadow region has had so little rain in the last four years that residents don’t have enough water to flush into toilets.

- In one of the region’s worst-hit districts, Beed, the dam that supplies water to people has nearly dried up due to lack of rain, leaving civic officials in a fix.

- It is lower class people who still do not have toilets and defecate in the open.

- But water scarcity has in a way reduced the prevalence of open defecation. Almost 70 per cent of the population now migrates to distant places like those in western Maharashtra and Karnataka in search of work.

The last push

- Call it the result of a strong political will or a multipronged assault on a nagging problem, what India is witnessing now is no less than a civilizational leap forward.

- Till five years ago, open defecation was a way of life for most in the country.

- The government was over and again pulled up at international platforms for hosting 60 per cent of the global population that defecates in the open.

- When the United Nations prepared the list of 17 sustainable development goals (SDGs) to be achieved by 2030, one of its foremost agendas required countries to “achieve access to adequate and equitable sanitation and hygiene for all and end open defecation”.

- Meeting SDG 6.2 then seemed a humongous task for India that topped the list of laggard countries and is often described as an Asian enigma by researchers.

Thirty-year journey to ODF

The fight for open defecation-free status is far from over

- Rural India is so densely settled that open defecation spreads diseases, killing and harming children.

- Open defecation still exists, especially in the multiply disadvantaged, densely populated villages of rural north India. Such was the pace that India was on in the 2015-16 Demographic and Health Survey.

- Open defecation is an important challenge in these four states: Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh.

- However, the decline in open defecation from 2014 to 2018 in these states was, according to statistical accounting, entirely due to increasing latrine ownership not to behavioural change. The fraction of latrine owners who defecate in the open did not change over these four years.

Sustaining ODF a multi-faceted process

- Bangladesh took 15 years to become ODF, while Thailand took 40.

- India has much to celebrate. Ever since the Mission started, the country has reduced open defecation at an unprecedented speed and scale.

- Many rural communities have strongly engaged with the sanitation agenda and, in a number of instances, women have been in the forefront.

- Making this progress permanent is now the key.

- The government has announced ODF Plus to ensure sustainability. To make the progress permanent and to achieve a more holistic impact on sanitation, efforts are on to educate rural communities on the management of organic waste, plastic waste, water conservation, etc.

- The World Bank is supporting Swachh Bharat Mission-Gramin (SBM-G) through a loan of $1.5 billion.

- This support incentivises states to achieve and sustain the ODF status and improve cleanliness in villages through solid and liquid waste management.

- Efforts focus on behavioural change on the ground, ensuring environmentally sustainable outcomes and building capacity of institutions for effective implementation.

Sustenance is the mantra

- Changing a habit requires time, effort and constant motivation. People need to know that the authorities, be it the sarpanch or the district administration, are with them, backing them and watching them.

- The programme has to be demand driven. Till people don’t ask for toilets, better sanitation and hygiene, it cannot be a success.

- People have to become responsible by forming self-help groups or small teams, which continuously motivate people to use toilets. This is the only way to sustain our ODF status.

- Rural areas are performing well in this, but there are problems in urban areas.

- A toilet can be maintained well when few people use it. If not for every household, toilets must be built for every two to three houses. Keys should be provided to people so that the toilets are not treated as community toilets.

- ODF can become sustainable if everybody becomes sensitive to the problem.

- The fight is much bigger than ODF. We have moved to ODF Plus. Our task is cut out. The fight is long. To sustain the achievement, we need constant effort, not interference.

Learning Aid

.png)