The State government of Karnataka has reiterated its stance on 80 percent reservation in jobs for locals (Kannadigas) in private firms.

Context

The State government of Karnataka has reiterated its stance on 80 percent reservation in jobs for locals (Kannadigas) in private firms.

Background:

- Reservation as we know has proved to be detrimental to the progress of India. While any sort of reservation was initially meant to uplift the backward and marginalised classed in the country.

- Now, increasingly states are seeking lion’s share.

- The Constitution of India does not provide for reservation in private sector, the Karnataka government seeks to overlook that and amend its Karnataka Industrial Employment (Standing Orders) Rules of 1961 to justify their means.

- Reservation for Kannadigas in the IT sector is a key area where the government wants to intervene.

- Karnataka’s reservation bill is similar to what neighboring Andhra Pradesh implemented last July.

- While countries introducing job quotas for their citizens in times of economic distress and rising unemployment to keep migrants away is common — Saudi Arabia, Oman, Qatar and Switzerland being recent examples — states within a country doing so is not as prevalent.

- The states in support of such a policy provides an argument that it is the state’s responsibility to fulfill aspirations of its people, also since the state is providing incentives, the industries should not have any problem in following its directions.

Analysis

Who are Kannadigas?

- The state government has not stated who will be considered a Kannadiga.

- But it is likely that only those who have lived in Karnataka for at least 15 years and can speak, read and write Kannada reasonably well will qualify as Kannadigas.

- This definition was used by the committee headed by former union minister Sarojini Mahishi.

- The committee, which submitted its report in 1986, recommended a slew of quotas for Kannadigas, including 65-100% in state and central government departments and public sector units, and all jobs in the private sector except in senior and skilled positions.

- At one point of time, close to 27 percent of Bengaluru’s population comprised Kannadigas, now it has dropped to nearly 21 percent.

- It also indicates that there is a drop in the number of Kannadigas getting jobs.

- A committee under Sarojini Mahishi (now the leader of the Janata Party) was appointed to look into the matter of reservation in the state of Karnataka in 1983.

- It submitted its report which sought reservation for Kannadigas in central government department for ‘Group C’ and ‘Group D’ jobs.

What is ‘Locals First’ Policy?

- The ‘locals first’ policy implies that jobs that will be created in a state will be first offered to only people who belong to that state i.e., local people.

- This policy is becoming popular due to unemployment and fear of some locals who believe that their jobs are being taken away from them and provided to the people not belonging to the state.

- However, it has been seen that such laws remain in the statute books and are not enforced.

Assessing the case for nativism:

- Nativism, the cry for job protection of locals, is rearing its head again in India.

- In 2019, the newly elected government of Andhra Pradesh passed the Andhra Pradesh Employment of Local Candidates in the Industries/Factories Bill, 2019.

As per this law, 75% of jobs in industries are to be reserved for locals. - Madhya Pradesh is mulling over a similar law. Goa and Odisha may be next in line. Maharashtra and Assam have seen similar nativist agitations for decades in varying intensities.

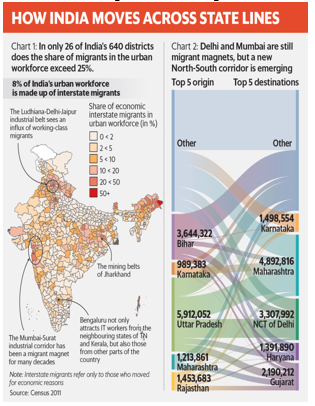

- The 2011 census shows that state-level job reservation for native residents is unnecessary and driven by politics.

- The calls for nativism should also be seen against the backdrop of the economic slowdown. The best way to grow out of nativism is to ensure economic recovery.

How is it linked to migration?

- The new insight the census offers is a decisive directional shift in India’s migration story—with the Hindi heartland exodus no longer directed at just the economic hubs along the western coast, but also along a newly emerging north-to-south corridor.

- More Indians are also moving across state lines in search of better educational opportunities. But despite these newly emerging trails, in a majority of India’s districts, less than one in 10 (or less than 10%) of the urban workforce is an interstate migrant.

- In Madhya Pradesh, where there are calls for a quota for locals, that share is 5%.

Indian Constitution & Migration:

- The Constitution of India guarantees ‘freedom of movement’ and consequently employment within India through several provisions.

- Article 19 ensures that citizens can “move freely throughout the territory of India".

- Article 16 guarantees no birthplace-based discrimination in public employment.

- Article 15 guards against discrimination based on place of birth and Article 14 provides for equality before law irrespective of place of birth.

- Some of these Articles were invoked in a landmark 2014 case—

How migration affect employment opportunities for locals?

- The numbers on interstate migration should also influence the debate on ‘job protection for locals’.

- Census figures on absolute magnitudes of interstate migration are usually underestimates since they do not capture short-term and circular migration very well, but inferences can still be gleaned from growth rates and comparative percentages.

- As per the census, the stock of interstate migrants grew from 41 million in 2001 to 54 million in 2011, but the share in total population remained roughly the same at around 4%.

- Migration flows in the decade before the census rose from 20 million (1991-2001) to 26 million (2001-2011).

- Between 1991 and 2011, the share of interstate migration in overall internal migration also remained roughly constant at around 12% (19% for males and 10% for females).

- While migration rates surged between 2001 and 2011, the bulk of this surge came from migration within states rather than interstate migration.

- Between 2001 and 2011, the total number of interstate migrants who moved for economic reasons, in particular, rose marginally from 11.6 million to 13 million.

- Their share in the urban workforce hovered at only 8%, with substantial regional variation.

- In only 26 out of 640 districts did the figure exceed 25% and none of those districts were in Madhya Pradesh or Andhra Pradesh.

- Female interstate migration: Much of the interstate migration for women occurs as reciprocal flows in districts along state boundaries as marriage is a primary reason for migration, but the 2011 census shows a sharp pick up in interstate female migration for economic reasons such as employment or business.

- Male interstate migration: Over half of male interstate migration is for economic reasons but, even there, most interstate migration is confined to neighbouring states—barring large corridors from Uttar Pradesh and Bihar to Maharashtra (mainly Mumbai), Gujarat, and other relatively prosperous regions.

Why local quota is not a good idea?

- Job quotas are economic insanity. With GST (goods and services tax), we are trying to make India one national market, but with quotas for locals, we are going the other way.

- Having a law which mandates this quota is a violation of Article 14 of the Indian Constitution, which prohibits discrimination on the basis of religion, race, caste, sex or place of birth.

- Local reservation in the private sector may not be the ideal solution to tackle the unemployment crisis; in fact, it can deter the corporate sector from investing in states that come up with such a rule.

- The idea of reservations for locals also goes against the established fact that migration of labour is good for the economy. Many Indian states, Punjab, Gujarat, and Maharashtra, to name a few, have benefited from migrant labour.

- One India, one market. That was the hope when the goods and services tax (GST) was enacted. This idea of local reservation hits the ideal of one unified Indian market.

Suggestive measures:

- A better way to engage with the private sector would be to make the youth of a state employable with proper investments in education, health and skill development.

- The states may enact reservations in government jobs for scheduled castes, schedules tribes and educationally and socially backward classes, but not for local residents alone. Nor can they reserve jobs in the private sector.

- The central government should also take some complementary actions to comprehensively address how to achieve decent work and inclusive growth for all. These include, formalizing the informal economy, fostering accumulation of skills and growth for sustainable enterprises, promoting equal pay for work of equal value and strengthening social protection for workers.

In India, the calls for nativism and their critiques are not new, they tend to occur during periods of economic sluggishness. In the given situation, the only and best way to grow out of nativism is to ensure that the economy is back on track at the earliest.