With falling farm yields, exacerbated by climate effects, doubling farmers’ real income by FY23 will be difficult, which means continuing to subsidise fertiliser will work against the government’s stated goals for the agriculture sector.

Issue

With falling farm yields, exacerbated by climate effects, doubling farmers’ real income by FY23 will be difficult, which means continuing to subsidise fertiliser will work against the government’s stated goals for the agriculture sector. In this context, the fertilizer policy needs to be revisited.

Background

- Fertiliser, a productivity-enhancing input: In certain developing countries population growth is increasing faster than agricultural production. In this context, fertilizer is known to be a powerful productivity-enhancing input to agriculture which helps meet the needs of an increasing population.

- One-third of increase in cereal production worldwide, and 50 per cent of increase in India’s grain production has been attributed to fertilizer related factors.

- India’s experience with productivity-enhancing benefits of fertilisers prompted it to adopt a policy of subsidising fertilisers in the later part of the Green Revolution.

- But with the long-term structural adjustment programmes, the environment in the fertilizer sector has changed considerably since the 1990s.

- In 1977, India’s per hectare usage of NPK (nitrogenous, phosphatic and potassic) fertiliser was 24.9 kg.

- By FY19, the per hectare usage stood at 137.6 kg.

- Increased fertiliser usage also meant a concomitant spurt in agricultural production.

- Total food grain production increased over-three-fold from 1977-78 to FY19.

- Per capita availability of food increasing from 155.3 kg in 1976 to 180.3 kg in 2018.

- This has benefited India’s food security situation.

- Massive urea subsidy: Today, urea (N of NPK) accounts for 64% of the government’s subsidy for fertiliser, with 77% of its price being subsidised, while for P&K fertilisers it is just 30-35%.

- Between FY01 and FY19, urea subsidy increased from Rs 9,500 crore to Rs 45,000 crore, and as per FY20 Budget estimates it will be Rs 50,000 crore.

- Fertiliser subsidy has only an apparent benefit: Continuing with the fertiliser policy may seem sensible, especially given that the food grain requirement is going to go up, and the climate crisis impact predicted is going to be quite severe for India.

- Challenges are far severe: However, studies show that challenges rooted in the subsidy policy for the major stakeholders—farmers, industry and the government are so serious, and the consequences of excessive fertiliser use so severe, that subsidising and producing fertilisers in the country seems a bad proposition.

|

Classification of fertilisers:

|

Analysis

Development of fertiliser policy - Past to present

- Since independence, GoI has been regulating sale, price and quality of fertilizers. For this purpose, GoI passed the Fertilizer Control Order (FCO) under Essential commodity Act (EC Act) in the year 1957.

- Fertilizer is declared as an essential commodity under EC Act.

- Accordingly, it is the responsibility of State Governments to ensure supply of quality of fertilizers by the manufacturers/importers of fertilizers.

- Only fertilizers which meet standards of quality laid down in the FCO can be sold to the farmers.

- State Governments are empowered to draw samples of the fertilizers anywhere in the Country and take appropriate action against sellers of Non-Standard fertilizers.

- On recommendation of Maratha Committee, Retention Price Scheme (RPS) was first introduced for nitrogenous fertilizers in 1977, and later extended to other fertilisers.

- In early 1990s, India’s fiscal deficit was mounting and there was an impending danger of foreign exchange crisis.

- In order to contain the subsidy burden, Government then announced increase in prices of urea and other fertilisers.

- Government also set up a Joint Parliamentary Committee (JPC) on Fertilizer Pricing which concluded that the rise in subsidy was mainly due to increase in cost of imported fertilizers, de-valuation of rupee in July 1991 and the stagnant farm gate prices from 1980 to 1991.

- Government decontrolled all (P&K) fertilizers which were under RPS since 1977 except Urea which continued to remain under RPS.

- Since subsidy was retained in Urea while P&K fertilizers were decontrolled, prices of the latter in the market became comparatively high.

- As a result, production and consumption of nitrogenous fertilizers increased and consumption of P&K fertilizers decreased.

- This led to severe imbalance in consumption of NPK fertilizers.

- Fearing imbalance fertilization of the soil, un-affordability by farmers due to increase in P&K prices, Government announced Concession Scheme for P&K Fertilizers.

- During 1997 Department of Agriculture & Cooperation (DAC) also started an all India uniform Maximum Retail Price (MRP) for fertilisers.

- Responsibility of indicating MRP rested with State Governments.

- The difference in the delivered price of fertilizers at the farm gate and the MRP was compensated by the Government as subsidy to the manufacturers/importers.

- Nutrient Based Subsidy (NBS) Policy: The product based subsidy regime (concession scheme) was proving to be a losing proposition for all stake holders’ viz. farmers, industry and the Government, so to overcome the deficiency of concession scheme Government introduced NBS policy 2010 onwards. Under the NBS Policy, a fixed rate of subsidy (Rs./Kg) is announced on nutrients - ‘N’, ‘P’, ‘K’ and ‘S’ by the Government on annual basis.

- The market price of subsidized fertilizers, except Urea, is left open to manufacturers /marketers and determined through demand-supply dynamics, but any sale above the printed MRP is punishable under the EC Act.

- The distribution and movement of fertilizers is monitored online through web based “Fertilizer Monitoring System (FMS)”.

- The NBS is passed on to the farmers through the fertilizer industry. The payment of NBS to the manufacturers/importers is done by the government.

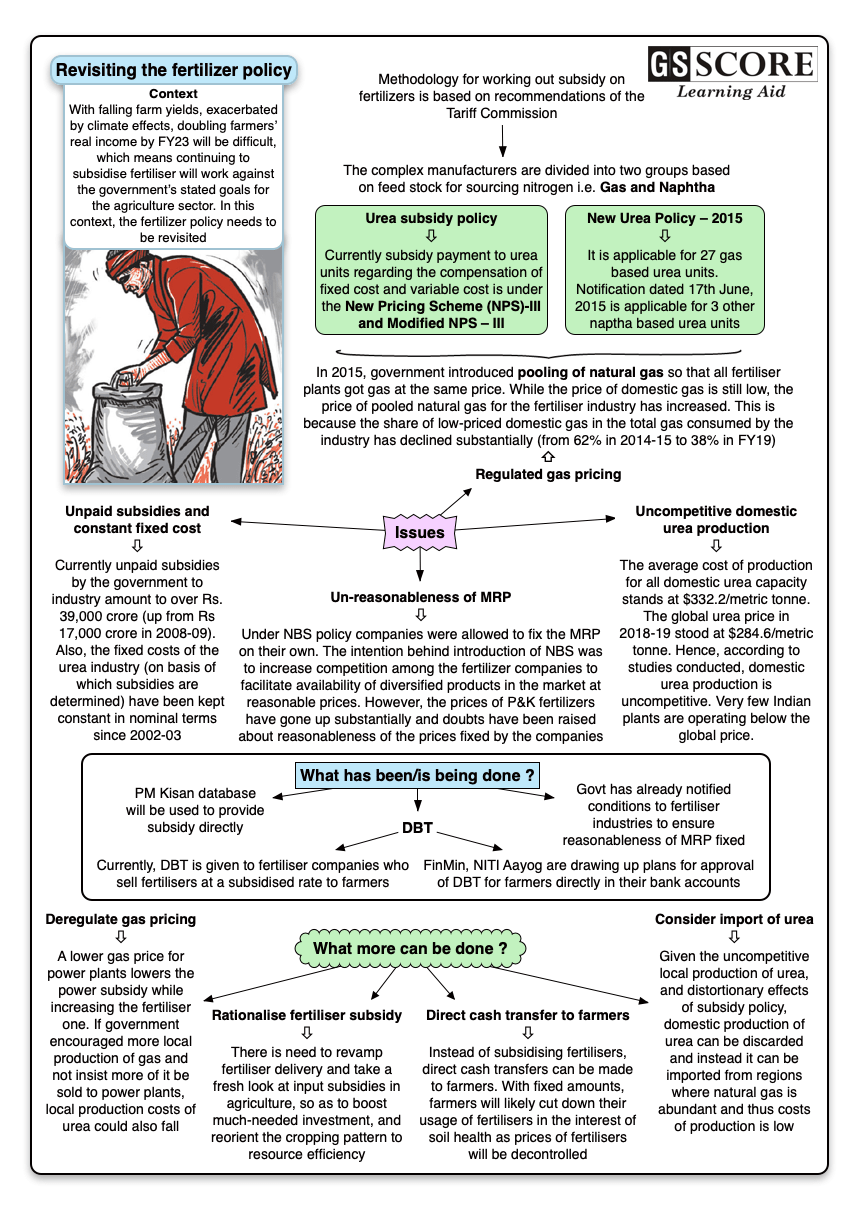

- Methodology for working out subsidy on fertilizers is based on recommendations of the Tariff Commission (TC).

- The complex manufacturers are divided into two groups based on feed stock for sourcing nitrogen i.e. Gas and Naphtha.

- Urea subsidy policy: Currently subsidy payment to urea units regarding the compensation of fixed cost and variable cost e.g. the cost of bag, water charges & electricity charges, is under the New Pricing Scheme (NPS)-III and Modified NPS – III.

- New Urea Policy – 2015 (2015-2019) is applicable for 27 gas based urea units.

- Notification dated 17th June, 2015 is applicable for 3 other naptha based urea units.

- Government has also notified New Investment Policy (NIP) 2012 with the objective to facilitate fresh investment, make India self and reduce import dependency in urea sector.

- Direct Benefit Transfer (DBT) for fertiliser subsidy payments to producers was introduced on a pilot basis in 2016, and it was rolled out nationwide in 2018.

- 100% subsidy is released to fertiliser companies based on actual sales made by the retailers to the beneficiaries.

- Sale of all subsidised fertilisers to farmers/buyers is made through point of sale (PoS) devices installed at each retailer shop and the beneficiaries are identified through Aadhaar card and voter identity card, among others.

Distortionary effects of subsidised fertiliser policy

- Mixed impact of Concession Scheme: The MRP of P&K fertilizers were much lower than its delivered cost. This led to increase in consumption of fertilizers during the last three decades and consequently increase in food grain production within the country. But it also caused fertiliser imbalance and poor soil health.

- Stagnation in agricultural productivity: Due rampant overuse of fertilisers it was observed in recent decades that the marginal response of agricultural productivity to additional fertilizer usage has fallen sharply, leading to near stagnation in agricultural productivity and consequently agricultural production.

- Multi/micro-nutrient deficiency: The disproportionate NPK application and lack of application of organic manures has contributed to rising multi-nutrient deficiency (of sulphur, iron, zinc, and manganese) leading to reduction in carbon content of the soil, was ultimately stagnating agricultural productivity.

- Fallen response ratio: In 2005, the crop response ratio to fertilisers had fallen to 3.7 kg grains/kg fertiliser, from 13 kg gains/kg fertiliser in 1970. Low crop response ratio means lower yields. To check falling productivity, hugely subsidised urea has led to worse overuse, drastically skewing the ideal usage ratio, and altering the soil chemistry further. It is a vicious cycle.

- Low profitability of fertiliser industry: The fertilizer sector worked in a highly regulated environment with cost of production and selling prices being determined by the Government. Due to this fertilizer industry suffered from low profitability as compared to other sectors.

- Lack of incentive for fertiliser industry: Growth of fertilizer industry stagnated with virtually no investments. The industry has no incentive to focus on farmers, leading to poor farm extension services, which were necessary to educate farmers about the modern fertilizer application techniques, soil health and promotion of soil-test based application of soil and crop specific fertilizers.

- Lack of innovation: The industry has no incentive to invest on modernization and efficiency. Innovation in fertilizer sector has also suffered as very few new products are introduced by fertilizer companies, since they get out priced by subsidized fertilizers.

- Increased subsidy burden of the government: Between 2005 and 2010, Government’s subsidy burden increased exponentially by 500% under the Concession Scheme. 94% of this increase was caused by increase in international prices of fertilizers and fertilizer inputs, and only 6% attributable to increase in consumption.

- Urea import: Given urea production stood at 23.9 mmt while consumption was 32 mmt in 2018-19, India is thus a major urea importer.

- Difference in prices of urea and P&K fertilisers: There is rampant overuse of urea as the difference in prices of urea and P&K fertilisers is quite large. Over time, the N P K content of the soil is thrown off balance.

- The indicated N:P:K usage for Indian soil is 4:2:1.

- It stood at 7:2.7:1 in 2000-01. It was 6.1:2.5:1 in 2017-18.

- In Punjab and Haryana, two of India’s top agrarian states, the ratio was 25.8:5.8:1 and 22.7:6.1:1, respectively.

- Subsidising pollution: Given Indian soils have relatively low nitrogen use efficiency; the bulk of urea applied contaminates ground water, surface water and the atmosphere. So, the current fertiliser policy is basically subsidising pollution.

- The bulk of the applied urea is lost as ammonia (NH3), di-nitrogen (N2) and NOx (nitrogen oxides).

- Ammonia gets converted to nitrates, increasing soil acidity, and NOx gases are major air pollutants.

- Excess nitrogen from urea leaching into the soil, and that of the deficiency of, for instance, caused by use of too little non-urea fertilisers;

- Health cost: Nitrate contamination of groundwater leads to conditions such as methaemoglobinaemia (commonly known as blue baby syndrome) and stunting. The contamination limits in Punjab, Haryana and Rajasthan have reached far beyond WHO prescribed safe limit.

Where does the problem lie?

- Uncompetitive domestic urea production: The average cost of production for all domestic urea capacity stands at $332.2/metric tonne. The global urea price in 2018-19 stood at $284.6/metric tonne, add to it bagging and handling charges, it was still lower ($300/metric tonne) than the domestic cost. Hence, according to studies conducted, domestic urea production is uncompetitive. Very few Indian plants are operating below the global price.

- Regulated gas pricing: In 2015, government introduced pooling of natural gas so that all fertiliser plants got gas at the same price. While the price of domestic gas is still low, the price of pooled natural gas for the fertiliser industry has increased. This is because the share of low-priced domestic gas in the total gas consumed by the industry has declined substantially (from 62% in 2014-15 to 38% in FY19). Part of the fall is because the share of supply of locally-produced gas to the power sector and other users has increased sharply.

- Un-reasonableness of MRP: Under NBS policy companies were allowed to fix the MRP on their own. The intention behind introduction of NBS was to increase competition among the fertilizer companies to facilitate availability of diversified products in the market at reasonable prices. However, the prices of P&K fertilizers have gone up substantially and doubts have been raised about reasonableness of the prices fixed by the companies.

- Prices have increased: The prices have gone up substantially also on account of increase in prices of raw materials / finished fertilizers in international market and depreciation of Indian rupee w.r.t US Dollar.

- Unpaid subsidies and constant fixed cost: Currently unpaid subsidies by the government to industry amount to over Rs. 39,000 crore (up from Rs 17,000 crore in 2008-09). Also, the fixed costs of the urea industry (on basis of which subsidies are determined) have been kept constant in nominal terms since 2002-03. The industry estimates its fixed costs to be much higher.

Policy suggestions and Way forward

- Fertilizer use is not an end in itself: Fertiliser use is only a means of achieving increased food production. Thus, increased food production/availability should be seen as an objective for the agriculture sector in the context of contributing to the broader macroeconomic objectives of society.

- Rationalise fertiliser subsidy: There is need to revamp fertiliser delivery and take a fresh look at input subsidies in agriculture, so as to boost much-needed investment, and reorient the cropping pattern to resource efficiency.

- Consider import of urea: Given the uncompetitive local production of urea, and distortionary effects of subsidy policy, domestic production of urea can be discarded and instead it can be imported from regions where natural gas is abundant and thus costs of production is low (for example, Gulf nations or Russia).

- We can also enter into long-term contracts with them; in years when global prices shoot up, India can possibly export urea.

- Direct cash transfer to farmers: Instead of subsidising fertilisers, direct cash transfers can be made to farmers. With fixed amounts, farmers will likely cut down their usage of fertilisers in the interest of soil health as prices of fertilisers will be decontrolled.

- In 2015, the High Level Shanta Kumar Committee recommended a direct cash subsidy of ‘about Rs 7,000/ha’ to farmers, while deregulating the fertiliser sector.

- Deregulate gas pricing: A lower gas price for power plants lowers the power subsidy while increasing the fertiliser one. If government encouraged more local production of gas and not insist more of it be sold to power plants, local production costs of urea could also fall.

- Changes already under consideration:

- Currently, DBT is given to fertiliser companies who sell fertilisers at a subsidised rate to farmers.

- FinMin, NITI Aayog are drawing up plans for approval of DBT for farmers directly in their bank accounts.

- PM Kisan database will be used to provide subsidy directly; landed marginal farmers will be targeted initially.

- Officials says a single amount can’t be transferred to every beneficiary because usage of fertiliser varies from region to region; for example, Punjab farmers consume more fertilisers than Tamil Nadu farmers.

- Government has already notified conditions to fertiliser industries to ensure reasonableness of MRP fixed.

Learning Aid