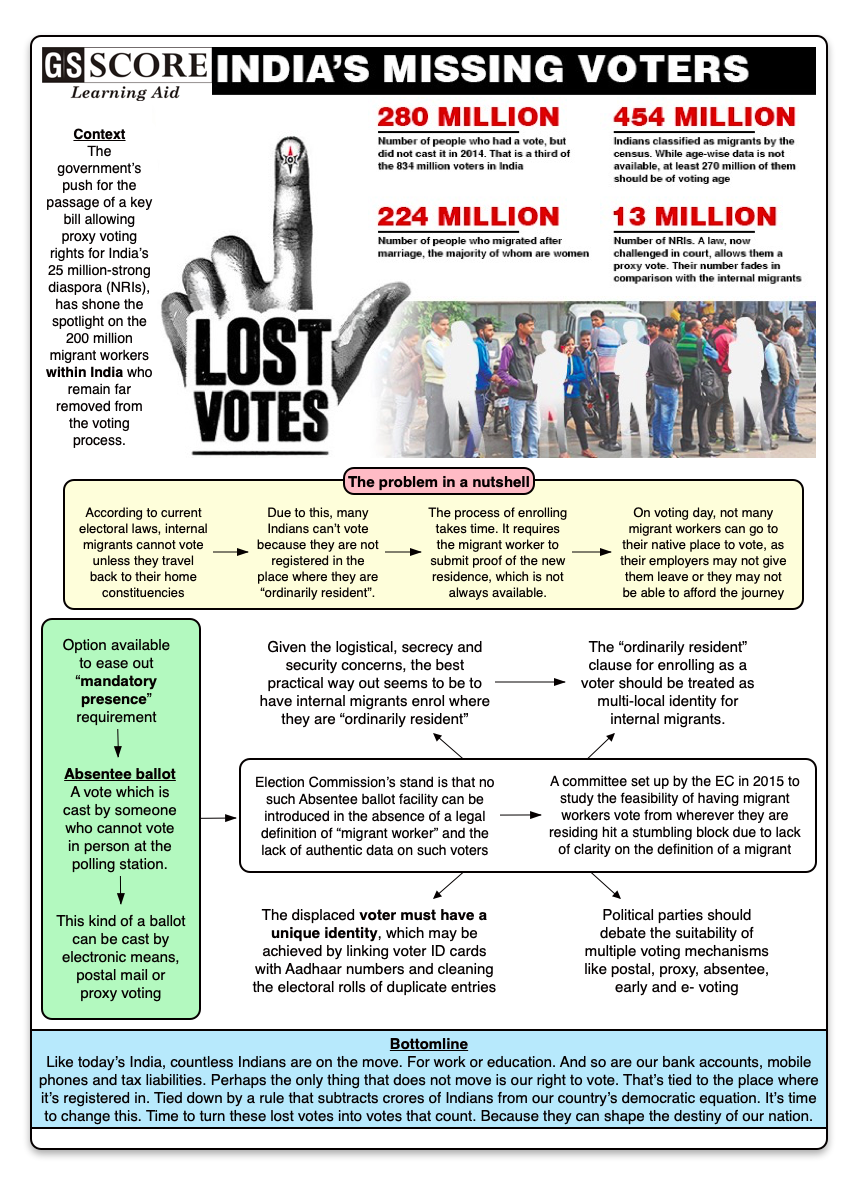

The government’s push for the passage of a key bill allowing proxy voting rights for India’s 25 million-strong diaspora — also known as non-resident Indians or NRIs — has shone the spotlight on the 200 million migrant workers within India who remain far removed from the voting process.

Issue

Context:

- The government’s push for the passage of a key bill allowing proxy voting rights for India’s 25 million-strong diaspora — also known as non-resident Indians or NRIs — has shone the spotlight on the 200 million migrant workers within India who remain far removed from the voting process.

- Civil rights groups feel that domestic migrants, who are direct stakeholders in the country’s future, deserve attention over the privileged NRIs, who have a lesser stake in India’s good governance and are only at best only fringe beneficiaries of its policies.

About:

- According to current electoral laws, internal migrants cannot vote unless they travel back to their home constituencies.

- Internal migration is an exponentially growing phenomenon. It shapes the economic, social, and political contours of India’s 29 states. Studies suggest that roughly 25 percent to 30 percent of Indians are internal migrants who have moved across district or state lines.

Background:

- According to the Representation of People Act, 1950, every person who is a citizen of India and not less than legal age of voting on the qualifying date and is ordinarily resident in a constituency shall be entitled to be registered in the electoral rolls for that constituency.

- The term ‘ordinarily resident’ excluded people with Indian citizenship who have migrated.

- This category included a person of Indian origin who is born outside India or a person of Indian origin who resides outside India— the NRIs.

- The NRIs are citizens of India. There is a prevailing view that by allowing the NRIs to vote they will become more involved in the nation-building process and the opportunities that India holds for them.

- A similar picture can be painted with respect to the “migrant workers within India”.

Analysis

Let vote move with voter: Why it’s not a reality yet?

- Many Indians can’t vote because they are not registered in the place where they are “ordinarily resident”.

- Not many migrants, most of whom are poor and not very educated, bother to have themselves enrolled every time they move to a new place for work.

- The process of enrolling takes time. It requires the migrant worker to submit proof of the new residence, which is not always available.

- On voting day, not many migrant workers can go to their native place to vote, as their employers may not give them leave or they may not be able to afford the journey.

What next:

Option available to ease out “mandatory presence” requirement

- Absentee ballot: A vote which is cast by someone who cannot vote in person at the polling station.

- This kind of a ballot can be cast by electronic means, postal mail or proxy voting.

The Election Commission’s stand:

- No such Absentee ballot facility can be introduced in the absence of a legal definition of “migrant worker” and the lack of authentic data on such voters.

- A committee set up by the EC in 2015 to study the feasibility of having migrant workers vote from wherever they are residing hit a stumbling block due to lack of clarity on the definition of a migrant.

- A study commissioned by EC on inclusive elections cited domestic migration rates computed by NSSO in 2007-08 and Census 2001 figures. NSSO in 2007-08 put their number at around 326 million (including those less than 18 years of age) while Census 2001 counted them at around 307 million.

- The study made a case for EC conducting a proper survey of domestic migrants before drawing up a policy on facilitating their vote.

The “internal” logistical challenge:

- Setting up special EVMs for various constituencies at designated polling booths and then bringing such EVMs to the counting center for a particular constituency is a challenge.

- The displaced voter must have a unique identity, which may be achieved by linking voter ID cards with Aadhaar numbers and cleaning the electoral rolls of duplicate entries.

- Section 20 of the Representation of the People (RP) Act says a person can be registered as a voter in any constituency where he is “ordinarily resident”. In case he migrates to another constituency, all s/he needs to do is fill up a voter enrolment form at the new place while requesting that her/his name be deleted from the old list.

- The application to be filed upon shifting to another constituency can be completed and submitted offline or online on the very day of moving to a new address. But, this is hardly done due to lack of awareness.

The Solution:

- Given the logistical, secrecy and security concerns, many feel it may be easier and more practical to have internal migrants enroll where they are “ordinarily resident”.

Tata Institute of Social Sciences had the following suggestions for EC to increase voter participation at polls:

- The “ordinarily resident” clause for enrolling as a voter should be treated as multi-local identity for internal migrants. EC says one has to be “ordinarily resident of the part or polling area of the constituency” where they want to be enrolled, which means one’s residential address is tied to the place of voting.

- Political parties should debate the suitability of multiple voting mechanisms like postal, proxy, absentee, early and e- voting.

- The short-term/seasonal migrants should be identified.

- The Contract Labour and the Inter-state Migrant Workmen (Regulation of Employment and Conditions of Service) Act, 1979, needs effective implementation. The Act aims to regulate the employment and safeguard interests of inter-state migrant workers, and as such requires registration of establishments employing them. That would provide a database of migrants for improving voter participation.

- Voter ID and Aadhaar number should be merged to aid portability of voting rights.

- A common, single point, one-time voluntary registration system should be introduced at the destination place for migrant workers.

- EC should organize campaigns to raise awareness about voting rights among domestic migrants.

Some Important Pointers:

- Internationally, right to vote and the right to public participation in government are recognized as basic human right. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (“UDHR”) provides that everyone has the right to take part in the government of their country, directly or through freely chosen representatives and the will of the people shall be the basis of the authority of government.

- Similarly, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (“ICCPR”) provides that every citizen shall have the right and the opportunity, without any of the distinctions and without unreasonable restrictions to take part in the conduct of public affairs, directly or through freely chosen representatives and to vote and to be elected at genuine periodic elections which shall be by universal and equal suffrage and shall be held by secret ballot, guaranteeing the free expression of the will of the elector.

- This right emphasizes that “no distinctions are permitted between citizens in the enjoyment of these rights on the grounds of race, Colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status.

Learning Aid

Practice Question:

After each election, parties look to the Election Commission (EC) to find out the percentage of people who voted for them. But what often gets overlooked is the number of people who did not turn up to vote. When every 3rd Indian is a migrant worker, make a case for deliberative democracy while ensuring that every vote counts.