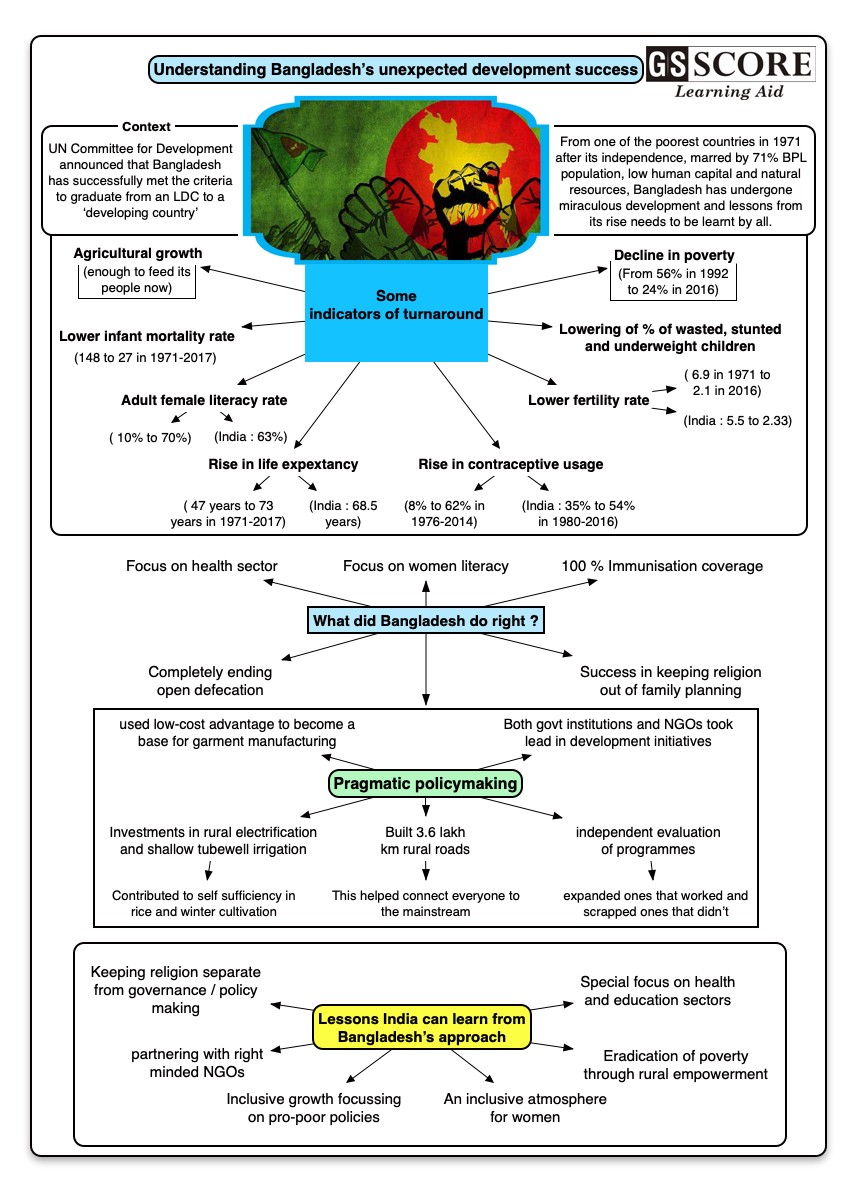

The United Nations Committee for Development Policy announced that Bangladesh had successfully met the criteria to graduate from a “least developed country” (LDC) to a “developing country” (DC).

Issue

Context:

- The United Nations Committee for Development Policy announced that Bangladesh had successfully met the criteria to graduate from a “least developed country” (LDC) to a “developing country” (DC).

- From an inauspicious set of adverse conditions including mass poverty, low human capital, few natural resources and a horrific exposure to devastating cyclones and famines, Bangladesh has become a Cinderella success story in terms of human development.

Background:

- At the time of independence in 1971, Bangladesh was one of the world’s poorest countries — on par with Rwanda, Mali, Burundi, Somalia, Ethiopia and Upper Volta (as Burkina Faso was then called).

- With a population of 67 million, an estimated 71% of whom lived below the national poverty line, it produced barely 10 million tonnes (mt) of rice and was the second largest food-aid recipient after Egypt from 1975 to 1992.

Bangladesh’s achievements:

- Decline in poverty: The country’s poverty headcount ratio was 56.6% even in 1992, falling only gradually to 48.9% by 2000. But since then, this has declined dramatically to 24.3% in 2016.

- Agriculture growth: While Bangladesh’s population has risen 2.5 times to 165 million since 1971, its rice production has soared 3.5 times to over 35 mt, enough to feed its people.

- More impressive is the improvement in social indicators.

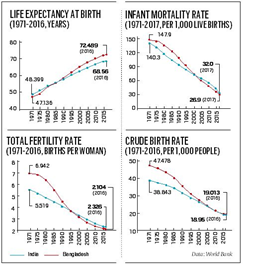

- Fertility rate: In 1971, Bangladesh’s total fertility rate — the number of children women bear on an average during their lifetime — was 6.94.

- That rate had, by 2016, dropped to 2.1, below the 2.33 for India (which actually had a lower rate of 5.52 in 1971).

- Increase use of contraceptives: Defying the so-called “Muslim” stereotype, the proportion of Bangladeshi women aged 15-49 years using contraceptives has increased from a mere 7.7% to 62.4% between 1976 and 2014.

- That figure for India was 53.5% in 2016, up from 35.3% in 1980, but indicating less impressive progress.

- Infant mortality rate (IMR): The success in population control has come alongside a massive fall in infant and under-five year mortality rates, from 147.9 and 221.4 per thousand live births respectively in 1971, to 26.9 and 32.4 in 2017.

- Increase in average life expectancy: The same period also recorded a jump in the country’s average life expectancy at birth — from 47.14 to 72.49 years (India: 68.56 years), and in the adult female literacy rate from under 10% to 70%-plus (India: 63%).

- Nutrition indicators (relating to prevalence of stunting (low height-for-age), wasting (low weight-for-height), and underweight (low weight-for-age) amongst children under 5): Between 1997 and 2017, these ratios for Bangladesh have dipped from 59.7%, 20.6% and 52.5% to 31%, 8%, and 22% respectively.

- Bangladesh, once considered a basket case, is today a country that can impart to all its neighbours including India, some excellent lessons in development.

Analysis

Reasons for such good indicators:

- Focus on health sector: Parents are likely to produce fewer children when they are sure about their survival.

- Women literacy: education makes women more aware of the need for family planning, apart from delaying the age of marriage.

- Immunisation coverage, which for the four standard vaccines — BCG, DTP, oral polio and measles — was 1%-2% in Bangladesh until 1985. That coverage is now near 100%.

- Open defecation, which Bangladesh practically eradicated by 2015. That was around the time India had launched the Swachh Bharat Mission, with roughly 40% of its population still practicing what is a major source of waterborne diseases from cholera and dysentery to hepatitis.

- Oral Rehydration Solution (ORS), a simple electrolyte blend of salt, sugar and clean water that Bangladeshi women were taught to make and administer to children suffering severe dehydration from diarrhoea. This homemade solution, later upscaled to pre-packed oral rehydration salts, proved much cheaper and more effective in rural areas than saline intravenous drips.

- Institutions involvement: Behind these accomplishments are institutions that include not just the big NGOs such as Sir Fazle Hasan Abed’s BRAC (which really pushed ORS on the ground), Social Marketing Company (which popularised contraception in Bangladesh), and Nobel Peace Laureate Prof Muhammad Yunus’s Grameen Bank (which pioneered microfinance), but even the likes of LGED or Local Government Engineering Department.

- The LGED, under its first chief engineer Quamrul Islam Siddique (a Verghese Kurien or E Sreedharan-like figure), was instrumental in building and managing Bangladesh’s rural roads network of some 360,000 km, one of the densest in the world.

- Investments in rural electrification and shallow tubewell irrigation making it possible for farmers to grow an additional high-yielding winter season Boro paddy crop, have contributed to Bangladesh becoming self-sufficient in rice.

- Country’s policymaking

- Clarity with regard to setting goals and a quiet pragmatism in meeting these.

- A culture of independent evaluation of programmes too was established, expanding the ones that worked and scrapping those that didn’t.

- The same pragmatism, perhaps, explains Bangladesh going ahead with commercial cultivation of genetically modified Bt brinjal, a technology that India has rejected despite being developed by an Indian company.

- Religion: The clerics could do nothing to stop family-planning efforts in Bangladesh, unlike in Pakistan, where the total fertility rate is still 3.5 and contraceptive prevalence among women of reproductive age is just 35.4%.

- A World Bank policy research paper points out that the most important factors for the decline of poverty in Bangladesh were higher real wages and higher productivity, while lower dependency ratios and a big increase in international remittances also helped.

- Bangladesh has successfully used its low-cost advantage to become a base for garment manufacturing. This has led to the migration of millions of people from rural areas into the manufacturing sector, with women being the biggest beneficiaries. Significantly, the share of employment in the formal sector in Bangladesh is 27.9%, well above that in India, and the proportion of working women in formal employment is even higher.

Lessons India can learn from the growth story of its neighbor are:

- Separation of religion and governance/policy making: The biggest lesson India can learn from Bangladesh today is to keep religious fundamentalism at bay and not allow so-called defenders of faith to dictate policy.

- Focus on health and education sector: Special focus should be given to health and education of women apart from others.

- Eradication of poverty and inclusion of women: Jobs for the masses are the surest means of pulling people out of poverty. Contrast India’s jobless growth. Manufacturing sector should be developed and participation of women workforce should be increased.

- Inclusive growth: Growth should be inclusive and more focus should be on the pro-poor policies so that people living below and near poverty can be included in the India’s growth.

- World Bank 2010 report that the role of the state has been critical through its pursuit of a six-point plan: by creating sound macroeconomic policies; improving disaster management; making sound investments in public health and education; partnering with NGOs; supporting family planning; and encouraging labour migration should be adopted in letter and spirit.

Conclusion:

The popular portrayal of Bangladesh in India is frequently unflattering — patronising at best and contemptuous at worst. Bangladeshis are “ghuspaithiye” — infiltrators and illegal immigrants — “termites” eating through India’s resources, and the alleged stealers of India’s cows and contributors to crime in the country. More than anything else, what this discourse betrays is ignorance. India should learn lessons from ‘Lesser’ tigers like Bangladesh and Indonesia from its neighbourhood only.

Learning Aid

Practice Questions:

- Bangladesh has become one of Asia’s most remarkable and unexpected success stories in recent years. In the light of the given statement discuss the reasons for this unexpected success. Also, suggest what India can learn from this?

- Bangladesh-India relations have reached a stage of maturity and with further upgrading and integration of infrastructure; bilateral ties can be expected to grow stronger in the future. Discuss