Context

The Government of India has aimed to expand India’s renewable energy installed capacity to 500 GW by 2030, from which 280 GW is expected to come from ‘Solar PV’.

- This makes the deployment of nearly 30 GW of solar capacity necessary every year.

Background

- Starting from less than 10 MW in 2010, India has added significant solar PV capacity over the past decade, achieving over 50 GW by 2022.

- By 2030, India is targeting about 500 GW of renewable energy deployment, out of which 280 GW is expected from solar PV. This necessitates the deployment of nearly 30 GW of solar capacity every year until 2030.

State of Solar energy in India:

- India has surpassed 50 GW of cumulative installed solar capacity, as on 28th February 2022.

- Of the 50 GW installed solar capacity, an overwhelming 42 GW comes from ground-mounted Solar Photovoltaic (PV) systems, and only 6.48 GW comes from Roof Top Solar (RTS); and 1.48 GW from off-grid solar PV.

- India’s capacity additions rank the country fifth in solar power deployment, contributing nearly 6.5% to the global cumulative capacity of 709.68 GW.

Challenges:

- Dependence on Imports: Indian solar companies depend heavily on imports, as India presently does not have enough module and cell manufacturing capacity. The demand-supply gap gets widened as we move up the value chain.

- Limited manufacturing capacity: India currently manufactures only 3.5 GW of solar cells and has a limited solar module manufacturing capacity of 15 GW.

- This is because, out of the 15 GW of module manufacturing capacity, only 3-4 GW of modules are technologically competitive and worthy of deployment in grid-based projects.

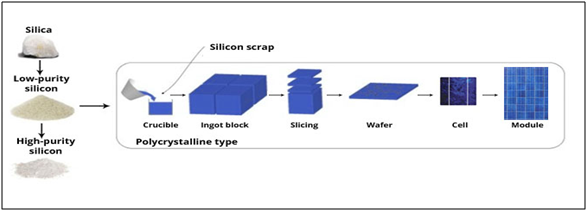

- India has no manufacturing capacity for solar wafers and polysilicon ingots, and currently imports 100% of silicon wafers and around 80% of cells even at the current deployment levels.

|

About polysilicon Ingots:

|

Raw Material Supply: The dependence is not restricted to silicon wafers. Raw materials like silver and aluminium metal pastes which are crucial for making electrical contacts are almost 100% imported.

-

- Silicon wafer, the most expensive raw material, is not manufactured in India.

- Poor investment in research: India has not invested enough in creating centres to try and test solar technologies in a cost-effective manner. E.g., IMEC Belgium or the Holst Centre in the Netherlands.

- Usage of Older Technology: Indian manufacturers depend on older Al-BSF technology (Aluminium Back Surface Field Solar Cells), which has low efficiencies of 18-19% at the cell level and 16-17% at the module level.

- Presently cell manufacturing worldwide has moved to PERC (22-23%), HJT (~24%),TOPCon (23-24%) and other newer technologies, yielding module efficiency of >21%.

- Presently cell manufacturing worldwide has moved to PERC (22-23%), HJT (~24%),TOPCon (23-24%) and other newer technologies, yielding module efficiency of >21%.

Land Issues:

- Producing more solar power for the same module size means more solar power from the same land area.

- Land, the most expensive part of solar projects, is scarce in India — and the Indian industry has no choice but to move towards newer and superior technologies as part of expansion plans.

- In such a scenario, floating solar plants offer a great deal of potential by utilizing the surface of water bodies, for example, Ramagundam Floating Solar PV Project at Ramagundam, Telangana.

Government Initiatives:

The government has recognized this demand-supply gap and is rolling out various policy initiatives to push and motivate the industry to work towards self-reliance in both for solar cells and modules. Some of the initiatives are:

- PLI scheme to Support Manufacturing: The Scheme has provisions for supporting the setting up of integrated manufacturing units of high-efficiency solar PV modules by providing Production Linked Incentive (PLI) on sales of such solar PV modules.

- The PLI scheme was conceived to scale up domestic manufacturing capability, accompanied by higher import substitution and employment generation.

- Levying Custom Duties on Import of Solar Cells & Modules: The Government has announced the imposition of Basic Customs Duty (BCD) on the import of solar PV cells and modules.

- It includes a 40% duty on the import of modules and a 25% duty on the import of cells.

- Domestic Content Requirement (DCR): Central Public Sector Undertaking (CPSU) Scheme Phase-II, PM-KUSUM, and Grid-connected Rooftop Solar Programme Phase-II, wherein government subsidies are given, it has been mandated to source solar PV cells and modules from domestic sources.

- It is mandatory to procure modules only from an approved list of manufacturers (ALMM) for projects that are connected to state/ central government grids; so far, only India-based manufacturers have been approved.

- Modified Special Incentive Package Scheme (M-SIPS): It's a scheme of the Ministry of Electronics & Information Technology.

- The scheme mainly provides a subsidy for capital expenditure on PV cells and modules 20% for investments in Special Economic Zones (SEZs) and 25% in non-SEZ.

- Solar Parks Scheme: The scheme facilitates and speeds up the installation of grid-connected solar power projects for electricity generation on a large scale. All the States and Union Territories are eligible for getting benefits under the scheme. The capacity of the solar parks shall be 500 MW and above.

- Central Public Sector Undertaking (CPSU) Scheme: A scheme for setting up 12 GW Grid- Connected Solar PV Power Projects by Central Public Sector Undertakings with domestic cells and modules is under implementation.

Required measures

- Strong industry-academia collaboration: It will result in the development of home-grown technologies which could assist the industry and its participants in an innovative manner.

- Boosting Local Manufacturing: India should move up the value chain by making components locally that could drive the price and quality of both cells and modules.

- Creation of PV manufacturing Parks: India needs to set up industry-like centres to work on specific technology domains with clear roadmaps and deliverables for the short and long term.

Conclusion

Although India is making big strides in the development of solar PV modules for power generation, it is still more of an assembly hub than a manufacturing one, and in the long term, it would be beneficial to move up the value chain by making components that could drive the price and quality of both cells and modules.

Some tax barriers and commercial incentives in the form of PLI schemes may offer a good start but they aren’t enough to become a manufacturing hub and fulfil India’s solar dream. A multipronged strategy that offers a pathway to achieve the goals requires, trained human resources, development of home-grown technologies, process learning, and substantial investments in several clusters.