History: Mass nationalism (1919-1939)

100th anniversary of Jallianwala Bagh massacre

Context

The cold-blooded massacre at Amritsar’s Jallianwala Bagh on April 13, 1919 (Baisakhi day) completed its 100 years in 2019. It marked a defining moment in the history of modern India and made the British presence morally untenable.

About

Jallianwala Bagh Massacre

- It is now a part of the world’s archives of state led crime. Troops under the command of Brigadier general (temporary rank) Reginald Dyer entered the garden, blocking the main entrance after them, took up position on a raised bank and on Dyer’s orders fired on the crowd for some 10 minutes, discharging 1,650 bullets at the peaceful protestors. They stopped only when the ammunition supply was almost exhausted. This event embodied a nation’s death-defying dignity in pain and hurt.

- It was an occasion to shed a silent tear for each of the innocent Indians who lost their lives on that Baisakhi dayand a mournful moment of reflection on colonial cruelty and irrational anger.

Causes of the event:

- The massacre was the result of the Anarchical and Revolutionary Crimes Act of 1919, famously known as the Rowlatt Act.

- Rowlatt Act curbed, in the name of war-time discipline, every conceivable civil liberty. This act enabled stricter control of the press, arrests without warrant, indefinite detention without trial. It empowered the police to search a place and arrest any person they disapproved of without warrant.

- The civilians assembled for a peaceful protest to condemn the arrest and deportation of two national leaders, Satya Pal and Saifuddin Kitchlew.

Aftermath of the massacre:

- Following the massacre, the Hunter Commission was appointed to investigate into the matter. The Commission in 1920 held Dyer guilty for his actions.

- The Bengali poet and Nobellaureate Rabindranath Tagore renounced the knighthood that he had received in 1915.

- Gandhi was initially hesitant to act, but he soon began organizing his first large-scale and sustained nonviolent protest (satyagraha) campaign, the non-cooperation movement(1920–22), which thrust him to prominence in the Indian nationalist struggle.

Konyak Dance

Context

During the Aoling Monyu festival, 4,700 Konyak Naga women danced together to set world record. The programme was organised to welcome the spring with an aim to preserve the cultural heritage of the people and also to promote tourism.

About

In an attempt to set a Guinness World Record for the "Largest Traditional Konyak Dance display", around 4700 women of Konyak tribe dressed in their traditional attires danced to the beats of traditional instruments and sang a ceremonial song for 5:01 minutes under the theme “Empowering Women for Cultural Heritage”.

What is Konyak?

- Konyak is one of the 16 Naga tribes and people of this community live mainly in the Mon district of Nagaland. It is one of the largest Naga tribe of Nagaland and their head hunting tradition is widely popular and known.

- They are easily distinguishable from other Naga tribes by their pierced ears; and tattoos which they have all over their faces, hands, chests, arms, and calves.

Aoling Monyu festival

- It is a major festival of Konyak Naga tribe celebrated in first week of the April every year. Being on the border of Myanmar, the neighbouring country also witnesses the pomp and gay of the Aoling Monyu festival.

- The festival is divided into three segments – 1st 3 days for weaving, feasting and sacrificing; 4th day for singing, dancing and head hunting; last 2 days for cleansing the house and the community for re-establishment of daily life. It also coincides with the start of Konak New Year. It is basically a harvest festival.

Purpose of this festival:

- To forgive each other so that everyone can work together and welcome the oncoming season of spring.

- Aoling is a time to offer sincere prayers to divine spirits for a good harvest. The people firmly believe in the generosity of the divine spirits who in turn blesses the people and their land.

- People also make small sacrifices of domestic animals for the respective purpose.

Difference between Hornbill festival and Aoling Monyu festival

- The Hornbill festival, which is often cited as festival of all festivals, celebrates the cultures of all the 17 tribes in Nagaland. However, Aoling is celebrated by a single tribe (Konyak) of Nagaland.

Kochi-Muziris Biennale

Fourth edition of Asia’s biggest contemporary art festival, the Kochi-Muziris Biennale – a 108-day event in December 2018.

About

More on news

- The exhibition was held at nine venues, eight of which are centred around West Kochi and Mattancherry at the confluence of Arabian Sea with Lake Vembanad, the longest lake in India.

- The theme for the 2018 biennale was “Possibilities for a Non-Alienated Life,” with Anita Dube, a contemporary artist, as its curator.

- About 100 artists from over 36 countries are participating in the art show known for its photo exhibitions, film screenings, paintings, installations, art education programs, and workshops.

Kochi-Muziris Biennale

- Inspired by renowned art festivals like the Venice Biennale, the Kochi-Muziris Biennale is the first biennale of India, providing a platform to showcase new artistic practices of the subcontinent and the world.

- The Kochi Biennale Foundation has hosted the festival since 2012 with the support of the state government and a few businesses.

What is the objective of the Biennale?

- To create a new language of cosmopolitanism and modernity that is rooted in the lived and living experience of Kochi.

- To establish itself as a centre for artistic engagement in India by drawing from the rich tradition of public action and public engagement in Kerala.

- To reflect the new confidence of Indian people who are slowly, but surely, building a new society that aims to be liberal, inclusive, egalitarian and democratic.

- To explore the hidden energies latent in India’s past and present artistic traditions and invent a new language of coexistence and cosmopolitanism that celebrates the multiple identities people live with.

Mass Nationalisation 1919-1939

1. Introduction to the Struggle for Swaraj:

- The third and the last phase of the national movement began in 1919 when the era of popular mass movements was initiated. The Indian people waged perhaps the greatest mass struggle in world history and India’s national revolution was victorious.

- A new political situation was maturing during the War years, 1914—18. Nationalism had gathered its forces and the nationalists were expecting major political gains after the war; and they were willing to fight back if their expectations were thwarted. The economic situation in the post-War years had taken a turn for the worse.

- There was first a rise in prices and then a depression in economic activity. Indian industries, which had prospered during the War because foreign imports of manufactured goods had ceased, now faced losses and closure. Moreover, foreign capital now began to be invested in India on a large scale.

- The Indian industrialists wanted protection of their industries through imposition of high customs duties and grant of government aid; they realised that a strong nationalist movement and an independent Indian government alone could secure these. The workers and artisans, facing unemployment and high prices, also turned actively towards the nationalist movement.

- Indian soldiers, who returned from their triumphs in Africa, Asia and Europe, imparted some of their confidence and their knowledge of the wide world to the rural areas. The peasantry, groaning under deepening poverty and high taxation, was waiting for a lead.

- The urban, educated Indians faced increasing unemployment. Thus all sections of Indian society were suffering economic hardships, compounded by droughts, high prices and epidemics.

- The international situation was also favourable to the resurgence of nationalism. The First World War gave a tremendous impetus to nationalism all over Asia and Africa. In order to win popular support for their War effort, the Allied nations—Britain, the United States, France, Italy and Japan—promised a new era of democracy and national self-determination to all the peoples of the world.

- But after their victory, they showed little willingness to end the colonial system. On the contrary, at the Paris Peace Conference, and in the different peace settlements, all the wartime promises were forgotten and, in fact, betrayed.

- The ex-colonies of the defeated powers, Germany and Turkey, in Africa, West Asia and East Asia were divided among the victorious powers. A militant nationalism, born out of a strong sense of disillusionment, began to arise everywhere in Asia and Africa.

- In India, while the British government made a half-hearted attempt at constitutional reform, it also made it clear that it had no intention of parting with political power or even sharing it with Indians.

- Another major consequence of the World War was the erosion of the White man’s prestige. The European powers had from the beginning of their imperialism utilised the notion of racial and cultural superiority to maintain their supremacy.

- But during the War, both sides carried on intense propaganda against each other, exposing the opponent’s brutal and uncivilized colonial record. Naturally, the people of the colonies tended to believe both sides and to lose their awe of the White man’s superiority.

- A major impetus to the national movements in the colonies was given by the impact of the Russian Revolution. On 7 November 1917, the Bolshevik (Communist) Party, led by V I. Lenin, overthrew the Czarist regime in Russia and declared the formation of the first socialist state, the Soviet Union, in the history of the world.

- The new Soviet regime electrified the colonial world by unilaterally renouncing its imperialist rights in China and other parts of Asia, by granting the right of self-determination to the former Czarist colonies in Asia and by giving an equal status to the Asian nationalities within its border, which had been oppressed as inferior and conquered peoples by the previous regime.

- The Russian Revolution put heart into the colonial people. It brought home to the colonial people the important lesson that immense strength and energy resided in the common people.

- If the unarmed peasants and workers could carry out a revolution against their domestic tyrants, then the people of the subject nations too could fight for their independence provided they were equally well united, organised and determined to fight for freedom.

- The nationalist movement in India was also affected by the fact that the rest of the Afro-Asian world was also convulsed by nationalist agitations after the War. Nationalism surged forward not only in India but also in Ireland, Turkey, Egypt and other Arab countries of Northern Africa and West Asia, Iran, Afghanistan, Burma, Malaya, Indonesia, Indo-China, the Philippines, China and Korea.

- The government, aware of the rising tide of nationalist and anti- government sentiments, once again decided to follow the policy of the ‘carrot and the stick’, in other words, of concessions and repression. The carrot was represented by the Montagu-Chelmsford Reforms.

2. The Montagu-Chelmsford Reforms:

- In 1918, Edwin Montagu, the Secretary of State, and Lord Chelmsford, the Viceroy, produced their scheme of constitutional reforms which led to the enactment of the Government of India Act of 1919. The Provincial Legislative Councils were enlarged and the majority of their members were to be elected.

- The provincial governments were given more powers under the system of Dyarchy. Under this system some subjects, such as finance and law and order, were called ‘reserved’ subjects and remained under the direct control of the Governor; others, such as education, public health and local self-government, were called ‘transferred’ subjects and were to be controlled by ministers responsible to the legislatures.

- This also meant that while some of the spending departments were transferred, the Governor retained complete control over the finances. The Governor could, moreover, overrule the ministers on any grounds that he considered special. At the centre, there were to be two houses of legislature. The lower house, the Legislative Assembly, was to have 41 nominated members out of a total strength of 144.

- The upper house, the Council of State, was to have 26 nominated and 34 elected members. The legislature had virtually no control over the Governor-General and his Executive Council.

- On the other hand, the central government had unrestricted control over the provincial governments. Moreover, the right to vote was severely restricted. In 1920, the total number of voters was 909,874 for the lower house and 17,364 for the upper house.

- Indian nationalists had, however, advanced far beyond such halting concessions. They were no longer willing to be satisfied with the shadow of political power. The Indian National Congress met in a special session at Bombay in August 1918 under the president-ship of Hasan Imam to consider the reform proposals. It condemned them as “disappointing and unsatisfactory” and demanded effective self- government instead.

- Some of the veteran Congress leaders led by Surendranath Banerjea were in favour of accepting the government proposals. They left the Congress at this time and founded the Indian Liberal Federation. They came to be known as Liberals and played a minor role in Indian politics hereafter.

3. The Rowlatt Act:

- While trying to appease Indians, the Government of India was ready with repression. Throughout the war, repression of nationalists had continued. The terrorists and revolutionaries had been hunted down, hanged and imprisoned. Many other nationalists such as Abul Kalam Azad had also been kept behind bars.

- The government now decided to arm itself with more far-reaching powers, which went against the accepted principles of rule of law, to be able to suppress those nationalists who would refuse to be satisfied with the official reforms. In March 1919 it passed the Rowlatt Act even though every single Indian member of the Central Legislative Council opposed it.

- This Act authorized the government to imprison any person without trial and conviction in a court of law. The Act would thus also enable the government to suspend the right of Habeas Corpus which had been the foundation of civil liberties in Britain.

4. Mahatma Gandhi Assumes Leadership:

- The Rowlatt Act came like a sudden blow. To the people of India, promised extension of democracy during the War, the government step appeared to be a cruel joke. It was like a hungry man, expecting bread, being offered stones. Instead of democratic progress had come further restriction of civil liberties. Unrest spread in the country and a powerful agitation against the Act arose.

- During this agitation, a new leader, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, took command of the nationalist movement. The new leader made good one of the basic weaknesses of the previous leadership. He had evolved in his struggle against racialism in South Africa a new form of struggle—non-cooperation—and a new technique of struggle—satyagraha—which could be put into practice against the British in India.

- He had, moreover, a basic sympathy for and understanding of the problems and psychology of the Indian peasantry. He was, therefore, able to appeal to it and bring it into the mainstream of the national movement. He was thus able to arouse and unite all sections of the Indian people in a militant mass national movement.

5. Gandhiji and his Ideas:

- K. Gandhi was born on 2 October 1869 at Porbandar in Gujarat. After getting his legal education in Britain, he went to South Africa to practice law.

- Imbued with a high sense of justice, he was revolted by the racial injustice, discrimination and degradation to which Indians had to submit in the South African colonies. Indian labourers who had gone to South Africa, and the merchants who followed were denied the right to vote. They had to register and pay a poll-tax.

- They could not reside except in prescribed locations which were insanitary and congested. Gandhi soon became the leader of the struggle against these conditions and during 1893-1914 was engaged in a heroic though unequal struggle against the racist authorities of South Africa.

- It was during this long struggle lasting nearly two decades that he evolved the technique of satyagraha based on truth and non-violence. The ideal satyagrahi was to be truthful and perfectly peaceful, but at the same time he would refuse to submit to what he considered wrong. He would accept suffering willingly in the course of struggle against the wrong-doer.

- This struggle was to be part of his love of truth. But even while resisting evil, he would love the evil-doer. Hatred would be alien to the nature of a true satyagrahi. He would, moreover, be utterly fearless.

- He would never bow down before evil whatever the consequences. In Gandhi’s eyes, non-violence was not a weapon of the weak and the cowardly. Only the strong and the brave could practice it. Even violence was preferable to cowardice.

- He once summed up his entire philosophy of life as follows:The only virtue I want to claim is truth and non-violence. I lay no claim to super-human powers: I want none.

- Another important aspect of Gandhi’s outlook was that he would not separate thought and practice, belief and action. His truth and non-violence were meant for daily living and not merely for high- sounding speeches and writings.

- Gandhiji, moreover, had an immense faith in the capacity of the common people to fight.

- Gandhiji returned to India in 1915 at the age of 46. He spent an entire year travelling all over India, understanding Indian conditions and the Indian people and then, in 1916, founded the Sabarmati Ashram at Ahmedabad where his friends and followers were to learn and practice the ideas of truth and non-violence. He also set out to experiment with his new method of struggle.

6. Champaran Satyagraha (1917):

- Gandhi’s first great experiment in satyagraha came in 1917 in Champaran, a district in Bihar. The peasantry on the indigo plantations in the district was excessively oppressed by European planters. They were compelled to grow indigo on at least 3/20th of their land and to sell it at prices fixed by the planters.

- Similar conditions had prevailed earlier in Bengal, but as a result of a major uprising during 1859—61 the peasants there had won their freedom from the indigo planters.

- Having heard of Gandhi’s campaigns in South Africa, several peasants of Champaran invited him to come and help them. Accompanied by Babu Rajendra Prasad, Mazhar-ul-Huq, J.B. Kripalani, Narhari Parekh and Mahadev Desai, Gandhiji reached Champaran in 1917 and began to conduct a detailed inquiry into the condition of the peasantry.

- The infuriated district officials ordered him to leave Champaran, but he defied the order and was willing to face trial and imprisonment.

- This forced the government to cancel its earlier order and to appoint a committee of inquiry on which Gandhiji served as a member. Ultimately, the disabilities from which the peasantry was suffering were reduced and Gandhiji won his first battle of civil disobedience in India. He also had a glimpse into the naked poverty in which the peasants of India lived.

7. Ahmedabad Mill Strike:

- In 1918, Mahatma Gandhi intervened in a dispute between the workers and mill-owners of Ahmedabad. He advised the workers to go on strike and to demand a 35 per cent increase in wages. But he insisted that the workers should not use violence against the employers during the strike.

- He undertook a fast unto death to strengthen the workers’ resolve to continue the strike. But his fast also put pressure on the mill-owners who relented on the fourth day and agreed to give the workers a 35 per cent increase in wages.

- In 1918, crops failed in the Kheda District in Gujarat but the government refused to remit land revenue and insisted on its full collection. Gandhiji supported the peasants and advised them to withhold payment of revenue till their demand for its remission was met.

- The struggle was withdrawn when it was learnt that the government had issued instructions that revenue should be recovered only from those peasants who could afford to pay. Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel was one of the many young persons who became Gandhiji’s followers during the Kheda peasant struggle.

- These experiences brought Gandhiji in close contact with the masses whose interests he actively espoused all his life. In fact, he was the first Indian nationalist leader who identified his life and his manner of living with the life of the common people. In time he became the symbol of poor India, nationalist India and rebellious India.

- Three other causes were very dear to Gandhi’s heart.

- The first was Hindu-Muslim unity; the second, the fight against untouchability; and the third, the raising of the social status of women in the country.

8. Satyagraha Against the Rowlatt Act:

- Along with other nationalists, Gandhiji was also aroused by the Rowlatt Act. In February 1919, he founded the Satyagraha Sabha whose members took a pledge to disobey the Act and thus to court arrest and imprisonment. Here was a new method of struggle. The nationalist movement, whether under moderate or extremist leadership, had hitherto confined its struggle to agitation.

- Big meetings and demonstrations, refusal to cooperate with the government, boycott of foreign cloth and schools, or individual acts of terrorism were the only forms of political work known to the nationalists. Satyagraha immediately raised the movement to a new, higher level. Nationalists could now act, instead of merely agitating and giving only verbal expression to their dissatisfaction and anger.

- The movement, moreover, was to rely increasingly on the political support of the peasants, artisans and the urban poor. Gandhiji asked the nationalist workers to go to the villages.

- That is where India lives, he said. He increasingly turned the face of nationalism towards the common man and the symbol of this transformation was to be khadi, or hand-spun and hand-woven cloth, which soon became the uniform of the nationalists.

- He spun daily to emphasise the dignity of labour and the value of self-reliance. India’s salvation would come, he said, when the masses were wakened from their sleep and became active in politics. And the people responded magnificently to Gandhi’s call.

- March and April 1919 witnessed a remarkable political awakening in India. Almost the entire country came to life. There were hartals, strikes, processions and demonstrations. The slogans of Hindu- Muslim unity filled the air. The entire country was electrified. The Indian people were no longer willing to submit to the degradation of foreign rule.

9. Jallianwala Bagh Massacre:

- The government was determined to suppress the mass agitation. It repeatedly lathi-charged and fired upon unarmed demonstrators at Bombay, Ahmedabad, Calcutta, Delhi and other cities. Gandhiji gave a call for a mighty hartal on 6 April 1919.

- The people responded with unprecedented enthusiasm. The government decided to meet the popular protest with repression, particularly in the Punjab. At this time was perpetrated one of the worst political crimes in modern history.

- A large but unarmed crowd had gathered on 13 April 1919 at Amritsar (in the Punjab) in the Jallianwala Bagh to protest against the arrest of their popular leaders, Saifuddin Kitchlew and Dr Satyapal.

- General Dyer, the military commander of Amritsar, decided to terrorize the people of Amritsar into complete submission. Jallianwala Bagh was a large open space which was enclosed on three sides by buildings and had only one exit. He surrounded the Bagh (garden) with his army unit, closed the exit with his troops and then ordered his men to shoot into the trapped crowd with rifles and machine-guns.

- They fired till their ammunition was exhausted. Thousands were killed and wounded. After this massacre, martial law was proclaimed throughout the Punjab and the people were submitted to the most uncivilized atrocities.

- A wave of horror ran through the country as the knowledge of the Punjab happenings spread. People saw, as if in a flash, the ugliness and brutality that lay behind the facade of civilisation that imperialism and foreign rule professed.

- Popular shock was expressed by the great poet and humanist Rabindranath Tagore who renounced his knighthood in protest .

10. The Khilafat and Non-Cooperation Movement (1919—22):

- A new stream came into the nationalist movement with the Khilafat movement. We know that the younger generation of educated Muslims and a section of traditional divines and theologians had been growing more and more radical and nationalist.

- The ground for common political action by Hindus and Muslims had already been prepared by the Lucknow Pact. The nationalist agitation against the Rowlatt Act had touched all the Indian people alike and brought Hindus and Muslims together in political agitation.

- Hindus and Muslims were handcuffed together, made to crawl together and drink water together, when ordinarily a Hindu would not drink water from the hands of a Muslim. In this atmosphere, the nationalist trend among the Muslims took the form of the Khilafat agitation.

- The politically-conscious Muslims were critical of the treatment meted out to the Ottoman (or Turkish) empire by Britain and its allies who had partitioned it and taken away Thrace from Turkey proper.

- The Muslims also felt that the power of the Sultan of Turkey, who was also regarded by many as the Caliph or the religious head of the Muslims, over the religious places of Islam should not be undermined. A Khilafat Committee was soon formed under the leadership of the Ali Brothers, Maulana Azad, Hakim Ajmal Khan and Hasrat Mohani, and a country-wide agitation was organised.

- The All-India Khilafat Conference held at Delhi in November 1919 decided to withdraw all cooperation from the government if their demands were not met. The Muslim League, now under the leadership of nationalists, gave full support to the National Congress and its agitation on political issues.

- On their part, the Congress leaders, including Lokamanya Tilak and Mahatma Gandhi, viewed the Khilafat agitation as a golden opportunity for cementing Hindu- Muslim unity and bringing the Muslim masses into the national movement.

- They realised that different sections of the people—Hindus, Muslims, Sikhs and Christians, capitalists and workers, peasants and artisans, women and youth, tribal people and people of different regions—would come into the national movement through the experience of fighting for their own different demands and seeing that the alien regime stood in opposition to them.

- Gandhiji looked upon the Khilafat agitation as “an opportunity of uniting Hindus and Mohammedans as would not arise in a hundred years.”

- Early in 1920 he declared that the Khilafat question overshadowed that of the constitutional reforms and the Punjab wrongs and announced that he would lead a movement of non-cooperation if the terms of peace with Turkey did not satisfy the Indian Muslims. In fact, very soon Gandhi became one of the leaders of the Khilafat movement.

- Meanwhile, the government had refused to annul the Rowlatt Act, make amends for the atrocities in the Punjab or satisfy the nationalist urge for self-government. In June 1920, an all-party conference met at Allahabad and approved a programme of boycott of schools, colleges and law courts. The Khilafat Committee launched a Non- Cooperation Movement on 31 August 1920.

- The Congress met in a special session in September 1920 at Calcutta, Only a few weeks earlier it had suffered a grievous loss— Lokamanya Tilak had passed away on 1 August at the age of 64. But his place was soon taken by Gandhiji, C.R. Das and Motilal Nehru. The Congress supported Gandhi’s plan for non-cooperation with the government till the Punjab and Khilafat wrongs were removed and swaraj established.

- The people were asked to boycott government educational institutions, law courts and legislatures; to give up foreign cloth; to surrender officially-conferred titles and honours; and to practice hand-spinning and hand-weaving for producing khadi.

- Later the programme would include resignation from government service and mass civil disobedience, including refusal to pay taxes. Congressmen immediately withdrew from elections, and the voters too largely boycotted them.

- This decision to defy in a most peaceful manner the government and its laws was endorsed at the annual session of the Congress held at Nagpur in December 1920. “The British people will have to beware,” declared Gandhiji at Nagpur, “that if they do not want to do justice, it will be the bounden duty of every Indian to destroy the empire.” The Nagpur session also made changes in the constitution of the Congress.

- Provincial Congress Committees were reorganized on the basis of linguistic areas. The Congress was now to be led by a Working Committee of 15 members, including the president and the secretaries. This would enable the Congress to function as a continuous political organisation and would provide it with the machinery for implementing its resolutions.

- The Congress organisation was to reach down to the villages, small towns and mohallas, and its membership fee was reduced to 4 annas (25 paise of today) per year to enable the rural and urban poor to become members.

- The Congress now changed its character. It became the organizer and leader of the masses in their national struggle for freedom from foreign rule. There was a general feeling of exhilaration. Political freedom might come years later but the people had begun to shake off their slavish mentality.

- It was as if the very air that India breathed had changed. The joy and enthusiasm of those days was something special, for the sleeping giant was beginning to awake. Moreover, Hindus and Muslims were marching together shoulder to shoulder. At the same time, some of the older leaders now left the Congress.

- They did not like the new turn that the national movement had taken. They still believed in the traditional methods of agitation and political work which were strictly confined within the four walls of the law.

- They opposed the organisation of the masses, hartals, strikes, satyagraha, breaking of laws, courting of imprisonment and other forms of militant struggle. Muhammad Ali Jinnah, G.S. Khaparde, Bipin Chandra Pal and Annie Besant were among the prominent leaders who left the Congress during this period.

- The years 1921 and 1922 were to witness an unprecedented movement of the Indian people. Thousands of students left government schools and colleges and joined national schools and colleges. It was at this time that the Jamia Millia Islamia (National Muslim University) of Aligarh, the Bihar Vidyapith, the Kashi Vidyapith and the Gujarat Vidyapith came into existence.

- The Jamia Millia later shifted to Delhi. Acharya Narendra Dev, Dr Zakir Husain and Lala Lajpat Rai were among the many distinguished teachers at these national colleges and universities. Hundreds of lawyers, including Chittaranjan Das, popularly known as Deshbandhu, Motilal Nehru, Rajendra Prasad, Saifuddin Kitchlew, C. Rajagopalachari, Sardar Patel, T. Prakasam and Asaf Ali gave up their lucrative legal practice.

- The Tilak Swarajya Fund was started to finance the non-cooperation movement and within six months over a crore of rupees were subscribed. Women showed great enthusiasm and freely offered their jewellery. Boycott of foreign cloth became a mass movement. Huge bonfires of foreign cloth were organised all over the land.

- Khadi soon became a symbol of freedom. In July 1921, the All-India Khilafat Committee passed a resolution declaring that no Muslim should serve in the British-Indian army. In September the Ali Brothers were arrested for ‘sedition’.

- Immediately, Gandhiji gave a call for repetition of this resolution at hundreds of meetings. Fifty members of the All-India Congress Committee issued a similar declaration that no Indian should serve a government which degraded India socially, economically and politically. The Congress Working Committee issued a similar statement.

- The Congress now decided to raise the movement to a higher level. It permitted the Congress Committee of a province to start civil disobedience or disobedience of British laws, including nonpayment of taxes, if in its opinion the people were ready for it.

- The government again took recourse to repression. The activities of the Congress and Khilafat volunteers, who had begun to drill together and thus unite Hindu and Muslim political workers at lower levels, were declared illegal. By the end of 1921 all important nationalist leaders, except Gandhiji, were behind bars along with 3000 others.

- In November 1921 huge demonstrations greeted the Prince of Wales, heir to the British throne, during his tour of India. He had been asked by the government to come to India to encourage loyalty among the people and the princes. In Bombay, the government tried to suppress the demonstration, killing 53 persons and wounding about 400 more.

- The annual session of the Congress, meeting at Ahmedabad in December 1921, passed a resolution affirming “the fixed determination of the Congress to continue the programme of non-violent non-cooperation with greater vigour than hitherto … till the Punjab and Khilafat wrongs were redressed and Swarajya is established.”

- The resolution urged all Indians, and in particular students, “quietly and without any demonstration to offer themselves for arrest by belonging to the volunteer organisations.”

- All such satyagrahis were to take a pledge to “remain non-violent in word and deed,” to promote unity among Hindus, Muslims, Sikhs, Parsis, Christians and Jews, and to practice swadeshi and wear only khadi.

- A Hindu volunteer was also to undertake to fight actively against untouchability. The resolution also called upon the people to organise, whenever possible, individual or mass civil disobedience along nonviolent lines.

- The people now waited impatiently for the call for further struggle. The movement had, moreover, spread deep among the masses. Thousands of peasants in Uttar Pradesh and Bengal had responded to the call of non-cooperation. In parts of Uttar Pradesh, tenants refused to pay illegal dues to the zamindars.

- In the Punjab the Sikhs were leading a non-violent movement, known as the Akali movement, to remove corrupt mahants from the Gurudwaras, their places of worship. In Assam, tea-plantation labourers went on strike. The peasants of Midnapore refused to pay Union Board taxes. A powerful agitation led by Duggirala Gopalakrishnayya developed in Guntur district.

- The whole population of Chirala, a town in that district, refused to pay municipal taxes and moved out of town. All village officers resigned in Peddanadipadu. In Malabar (northern Kerala) the Moplahs, or Muslim peasants, created a powerful anti-zamindar movement.

- The Viceroy wrote to the Secretary of State in February 1919 that “The lower classes in the towns have been seriously affected by the Non-Cooperation Movement…. In certain areas the peasantry have been affected, particularly in parts of Assam valley, United Provinces, Bihar and Orissa, and Bengal.”

- On 1 February 1922, Mahatma Gandhi announced that he would start mass civil disobedience, including non-payment of taxes, unless within seven days the political prisoners were released and the press freed from government control.

- This mood of struggle was soon transformed into retreat. On 5 February, a Congress procession of 3000 peasants at Chauri Chaura, a village in the Gorakhpur District of Uttar Pradesh, was fired upon by the police. The angry crowd attacked and burnt the police station causing the death of 22 policemen. Other incidents of violence by crowds had occurred earlier in different parts of the country.

- Gandhiji was afraid that in this moment of popular ferment and excitement, the movement might easily take a violent turn. He was convinced that the nationalist workers had not yet properly understood nor learnt the practice of non-violence without which, he was convinced, civil disobedience could not be a success.

- Apart from the fact that he would have nothing to do with violence, he also perhaps believed that the British would be able to easily crush a violent movement, for people had not yet built up enough strength and stamina to resist massive government repression. He therefore decided to suspend the nationalist campaign.

- The Congress Working Committee met at Bardoli in Gujarat on 12 February, and passed a resolution stopping all activities which would lead to breaking of laws. It urged Congressmen to donate their time to the constructive programme—popularization of the charkha, national schools, temperance, removal of untouchability and promotion of Hindu-Muslim unity.

- The Bardoli resolution stunned the country and had a mixed reception among the bewildered nationalists. While some had implicit faith in Gandhiji and believed that the retreat was a part of the Gandhian strategy of struggle, others, especially the younger nationalists, resented this decision to retreat.

- Many other young leaders such as Jawaharlal Nehru had a similar reaction. But both the people and the leaders had faith in Gandhiji and did not want to publicly disobey him. They accepted his decision without open opposition. The first Non-Cooperation and Civil Disobedience Movement virtually came to an end.

- The last act of the drama was played when the government decided to take full advantage of the situation and to strike hard. It arrested Mahatma Gandhi on 10 March 1922 and charged him with spreading disaffection against the government. Gandhiji was sentenced to six years’ imprisonment after a trial.

- Very soon the Khilafat question also lost relevance. The people of Turkey rose up under the leadership of Mustafa Kamal Pasha and, in November 1922, deprived the Sultan of his political power. Kamal Pasha took many measures to modernize Turkey and to make it a secular state.

- He abolished the Caliphate (or the institution of the Caliph) and separated the state from religion by eliminating Islam from the Constitution. He nationalized education, granted women extensive rights, introduced legal codes based on European models, took steps to develop agriculture and to introduce modern industries. All these steps broke the back of the Khilafat agitation.

- The Khilafat agitation had made an important contribution to the non-cooperation movement. It had brought urban Muslims into the nationalist movement and had been, thus, responsible in part for the feeling of nationalist enthusiasm and exhilaration that prevailed in the country in those days.

- Some historians have criticised it for mixing religion with politics. As a result, they say, religious consciousness spread to politics, and in the long run, the forces of communalism were strengthened. This is true to some extent. There was, of course, nothing wrong in the nationalist movement taking up a demand that affected Muslims only.

- It was inevitable that different sections of society would come to understand the need for freedom through their particular demands and experiences. The nationalist leadership, however, failed to some extent in raising the religious political consciousness of the Muslims to the higher plane of secular political consciousness.

- At the same time it should also be kept in view that the Khilafat agitation represented much wider feelings of the Muslims than their concern for the Caliph. It was in reality an aspect of the general spread of anti-imperialist feelings among the Muslims. These feelings found concrete expression on the Khilafat question. After all there was no protest in India when Kamal Pasha abolished the Caliphate in 1924.

- It may be noted at this stage that even though the Non- Cooperation and Civil Disobedience Movement had ended in apparent failure, the national movement had been strengthened in more than one way. Nationalist sentiments and the national movement had now reached the remotest corners of the land. Millions of peasants, artisans and urban poor had been brought into the national movement.

- All strata of Indian society had been politicized. Women had been drawn into the movement. It is this politicization and activation of millions of men and women that imparted a revolutionary character to the Indian national movement.

- The British rule was based on the twin notions that the British ruled India for the good of the Indians and that it was invincible and incapable of being overthrown. The first notion was challenged by the moderate nationalists who developed a powerful economic critique of colonial rule.

- It was now, during the mass phase of the national movement, that this critique was disseminated among the common people by youthful agitators through speeches, pamphlets, dramas, songs, prabhat pheries and newspapers. The notion of invincibility of the British rule was challenged by satyagraha and mass struggle.

- A major result of the Non-Cooperation Movement was that the Indian people lost their sense of fear—the brute strength of British power in India no longer frightened them. They had gained tremendous self-confidence and self-esteem, which no defeats and retreats could shake.

- This was expressed by Gandhiji when he declared that “the fight that was commenced in 1920 is a fight to the finish, whether it lasts one month or one year or many months or many years.”

11. The Swarajists:

- Major developments in Indian politics occurred during 1922—28. Immediately, the withdrawal of the Non-Cooperation Movement led to demoralisation in the nationalist ranks. Moreover, serious differences arose among the leaders who had to decide how to prevent the movement from lapsing into passivity.

- One school of thought headed by R. Das and Motilal Nehru advocated a new line of political activity under the changed conditions.

- They said that nationalists should end the boycott of the Legislative Councils, enter them, obstruct their working according to official plans, expose their weaknesses, transform them into arenas of political struggle and thus use them to arouse public enthusiasm.

- Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, Dr Ansari, Babu Rajendra Prasad and others, known as ‘no-changers’, opposed Council entry. They warned that legislative politics would lead to neglect of work among the masses, weaken nationalist fervour and create rivalries among the leaders.

- They, therefore, continued to emphasise the constructive programme of spinning, temperance, Hindu-Muslim unity, removal of untouchability and grassroots work in the villages and among the poor. This would, they said, gradually prepare the country for the new round of mass struggle.

- In December 1922, Das and Motilal Nehru formed the Congress-Khilafat Swarajya Party with C.R. Das as president and Motilal Nehru as one of the secretaries. The new party was to function as a group within the Congress. It accepted the Congress programme except in one respect—it would take part in Council elections.

- The Swarajists and the ‘no-changers’ now engaged in fierce political controversy. Even Gandhiji, who had been released on 5 February 1924 on grounds of health, failed in his efforts to unite them. But both were determined to avoid the disastrous experience of the 1907 split at Surat. On the advice of Gandhiji, the two groups agreed to remain in the Congress though they would work in their separate ways.

- Even though the Swarajists had little time for preparations, they did very well in the election of November 1923. They won 42 seats out of the 101 elected seats in the Central Legislative Assembly. With the cooperation of other Indian groups they repeatedly out-voted the government in the Central Assembly and in several of the Provincial Councils.

- They agitated through powerful speeches on questions of self-government, civil liberties and industrial development. In March 1925, they succeeded in electing Vithalbhai J. Patel, a leading nationalist leader, as the president (Speaker) of the Central Legislative Assembly.

- They filled the political void at a time when the national movement was recouping its strength. They also exposed the hollowness of the Reform Act of 1919. But they failed to change the policies of the authoritarian Government of India and found it necessary to walk out of the Central Assembly first in March 1926 and then in January 1930.

- In the meanwhile, the ‘no-changers’ carried on quiet, constructive work. Symbolic of this work were hundreds of ashrams that came up all over the country where young men and women promoted charkha and khadi, and worked among the lower castes and tribal people.

- Hundreds of National schools and colleges came up where young persons were trained in a non-colonial ideological framework. Moreover, constructive workers served as the backbone of the civil disobedience movements as their active organizers.

- While the Swarajists and the ‘no-changers’ worked in their own separate ways, there was no basic difference between the two, and, because they kept on the best of terms and recognised each other’s anti-imperialist character, they could readily unite later when the time was ripe for a new national struggle.

- Meanwhile, the nationalist movement and the Swarajists suffered another grievous blow in the death of C.R. Das in June 1925.

- As the Non-Cooperation Movement petered out and the people felt frustrated, communalism reared its ugly head. The communal elements took advantage of the situation to propagate their views and after 1923 the country was repeatedly plunged into communal riots.

- The Muslim League and the Hindu Mahasabha, which was founded in December 1917, once again became active. The result was that the growing feeling that all people were Indians first received a setback. Even the Swarajist Party, whose main leaders, Motilal Nehru and Das, were staunch nationalists, was split by communalism.

- A group known as ‘responsivists’, including Madan Mohan Malaviya, Lala Lajpat Rai and N.C. Kelkar, offered cooperation to the government so that the so-called Hindu interests might be safeguarded. They accused Motilal Nehru of letting down Hindus, of being anti-Hindu, of favouring cow-slaughter and of eating beef.

- The Muslim communalists were no less active in fighting for the loaves and fishes of office. Gandhiji, who had repeatedly asserted that “Hindu-Muslim unity must be our creed for all time and under all circumstances” tried to intervene and improve the situation.

- In September 1924, he went on a 21-day-fast at Delhi in Maulana Mohamed Ali’s house to do penance for the inhumanity revealed in the communal riots. But his efforts were of little avail.

- The situation in the country appeared to be dark indeed. There was general political apathy; Gandhi was living in retirement, the Swarajists were split, communalism was flourishing.

12. Civil Disobedience Movement:

Civil Disobedience (1930-31) Phase I:

- Civil disobedience of the laws of the unjust and tyrannical government is a strong and extreme form of political agitation according to Gandhi, which should be adopted only as a last resort. The Lahore Congress of 1929 had authorised the Working Committee to launch a programme of civil disobedience including non-payment of taxes. The committee also invested Gandhi with full powers to launch the movement.

- The 11 points ultimatum of Gandhiji to Lord Irwin after being ignored by the British Government made Gandhiji to launch the civil disobedience moment on 12th March 1930 with his famous Dandi March. (From Sabarmati Ashram to Dandi on Gujarat coast). On 6th April, Gandhiji reached Dandi, picked up a handful of salt and broke the salt law as a symbol of the Indian people’s refusal to live under British made laws and therefore under British rule.

- The movement now spread rapidly. Violation of salt laws all over the country was soon followed by defiance of forest laws in Maharashtra, Karnataka and the Central Provinces and the refusal to pay the rural Chaukidari tax in Eastern India.

- The people joined hartals, demonstrations and the campaign to boycott foreign goods and to refuse to pay-taxes. In many parts of the country, the peasants refused to pay land revenue and rent and had their lands confiscated. A notable feature of the movement was the wide participation of women.

- In North-western provinces, under the leadership of Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan, popularly known as ‘Frontier Gandhi’ the Pathans organised the society of Khudai Khidmatgars (or Servants of God) known popularly as Red Shirts.

- They were pledged to non-violence and the freedom struggle. In North-East Rani Gaidilieu raised the banner of rebellion against foreign rule. The government resorted to ruthless repression, lathi changes and firing. Over 90,000 Satyagrahis, including Gandhiji and other congress leaders were imprisoned and Congress declared illegal.

- Gandhi-lrwin Pact was signed in March 1931 due to the efforts of Sir Tej Bahadur Sapru, Dr. Jayakar and others to bring about a compromise between the government and the Congress. The Government agreed to withdraw all ordinances and end prosecutions, release all plitical prisoners, restore the confiscated property of the Satyagrahis and permitted the free collection or manufacture of salt. The Congress in turn agreed to suspend the civil disobedience movement and to participate in the Second Round-Table conference.

Phase II of Civil disobediance Movement (1932-34):

- On his return to India after the 2nd Round Table Conference Gandhiji resumed the Civil Disobedience movement in January 1932. The Congress was declared illegal by the government and it arrested most of the leading Congress leaders.

- The movement was gaining strength when it was suddenly side tracked with the announcement of Communal Award (1932) by the British Prime-minister Ramsay Mac Donald. The movement gradually waned. The Congress officially suspended the movement in May 1933 and withdrew it in May 1934.

Significance of Civil disobedience movement:

- It had the objective of achieving complete independence

- It involved deliberate violation of law and was evidently more militant

- There was wide participation of women.

- It was not marked by the same Hindu-Muslim unity which was witnessed during Non-cooperation movement.

Space station crew to blast off despite virus-hit build up

NIPER-Guwahati designs innovative 3D products to fight COVID-19

.jpg)

N.Korea test fires multiple short-range anti-ship missiles

US approves sale of anti-ship missiles, torpedoes to India

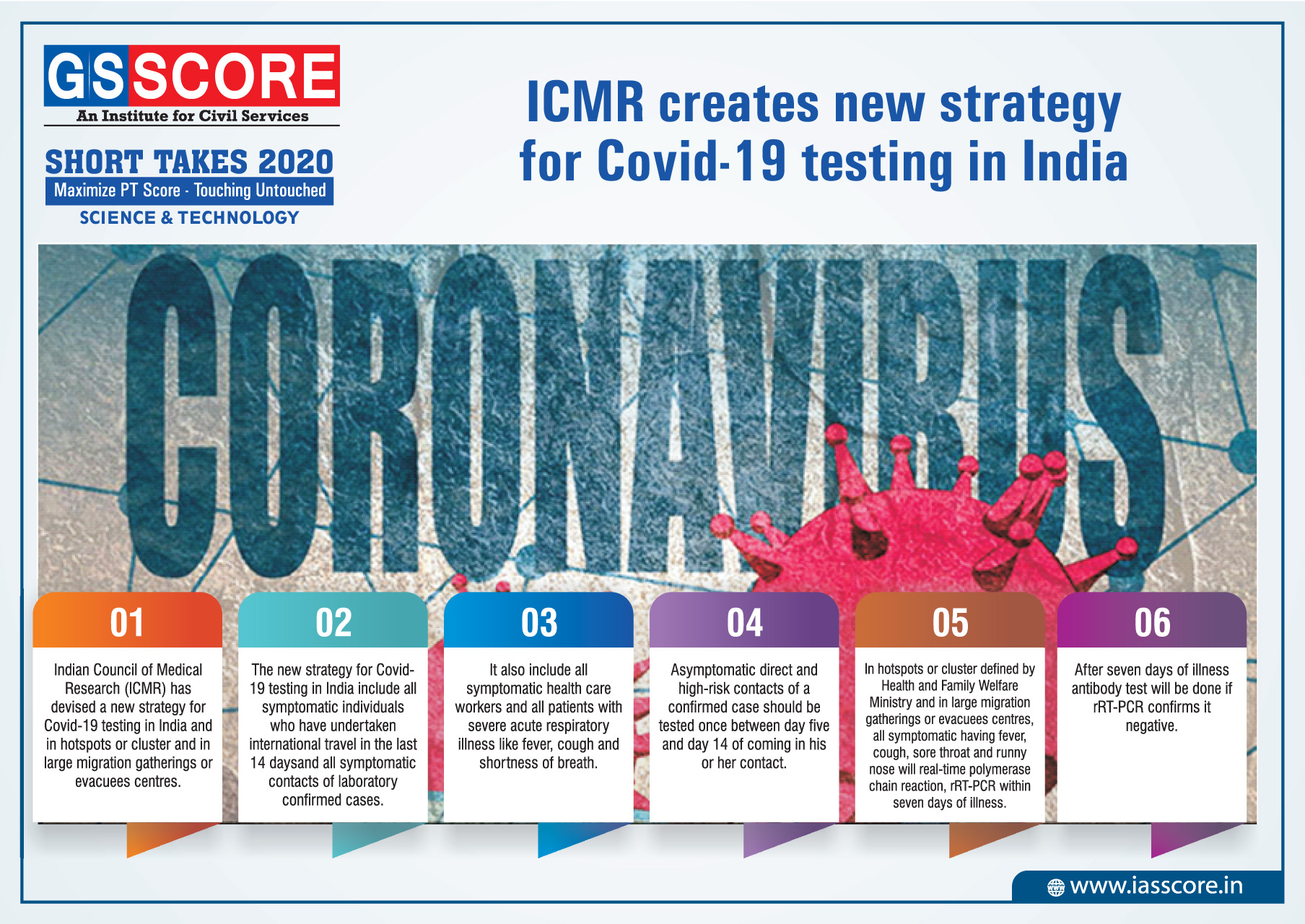

ICMR creates new strategy for Covid-19 testing in India