History: Mughal Period

Tulu Language

Context

There has been a growing demand to include Tulu in the Eighth Schedule of the Constitution. At present, Tulu is not an official language in India or any other country.

About

- Tulu is a Dravidian languagewhose speakers are concentrated in the region of Tulu Nadu, which comprises the districts of Dakshina Kannada and Udupi in Karnataka and the northern part of Kasaragod district of Kerala.

- Kasaragod district is called ‘Sapta bhasha Samgama Bhumi (the confluence of seven languages)’, and Tulu is among the seven.

- The oldest available inscriptions in Tulu are from the period between 14th to 15th century AD.

Case for Inclusion in the Eighth Schedule

- Global Efforts:The Yuelu Proclamation made by United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) at Changsha, China, in 2018 plays a central role in guiding the efforts of countries and regions around the world to protect linguistic resources and diversity.

- The United Nations General Assembly has proclaimed 2019 as the International Year of Indigenous Languages (IYIL). The IYIL 2019 strives to preserve, support and promote indigenous languages at the national, regional and international levels.

- Constitutional Safeguard: Article 29 of the Indian Constitution deals with the "Protection of interests of minorities". It states that any section of the citizens residing in any part of India having a distinct language, script or culture of its own, shall have the right to conserve the same.

- Number of Speakers:According to Census-2011, there are more than 18 lakh native speakers of Tulu in India. The Tulu-speaking people are larger in number than speakers of Manipuri and Sanskrit, which have the Eighth Schedule status.

- Literary Recognition:Robert Caldwell (1814-1891), in his book, A Comparative Grammar of the Dravidian or South-Indian Family of Languages, called Tulu as “one of the most highly developed languages of the Dravidian family”.

Advantages of Recognition in Eighth Schedule

- If included in the Eighth Schedule, Tulu would get the following benefits

- Recognition from the Sahitya Akademi.

- Translation of Tulu literary works into other languages.

- Members of Parliament (MP) and Member of the Legislative Assembly (MLA) could speak Tulu in Parliament and State Assemblies, respectively.

- Option to take competitive exams in Tulu including all-India competitive examinations like the Civil Services exam.

- Special funds from the Central government.

- Teaching of Tulu in primary and high school.

Way Forward

- India has a lot to learn from the Yuelu Proclamation. Placing of all the deserving languages on equal footing will promote social inclusion and national solidarity.

- It will reduce inequalities within the country to a great extent. So, Tulu, along with other deserving languages, should be included in the Eighth Schedule of the Constitution in order to substantially materialise the promise of equality of status and opportunity mentioned in the Preamble.

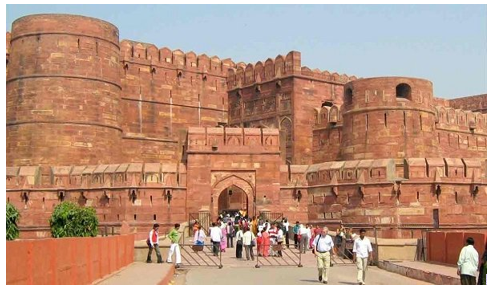

Bibi Ka Maqbara

Context

The marble domes of Bibi Ka Maqbara, the famous 17th-century Mughal-era monument in the city, are set to get a new shine.

About

Bibi Ka Maqbara:

- The structure, known as the ‘Taj of the Deccan’ because of its striking resemblance to the Taj Mahal, was built in 1668 by Azam Shah, the son of Aurangzeb to commemorate his mother Dilras Begum who was titled Rabia Durani post her death.

- Also called the Tomb of the Lady, Bibi Ka Maqbara was designed by Ataullah, the son of Ahmad Lahauri, the architect of the Taj Mahal which explains its appearance heavily based on the prime marvel.

- According to the "Tarikh Namah" of Ghulam Mustafa, the cost of construction of the mausoleum was Rs. 6,68,203 - 7,00,000.

- Bibi Ka Maqbara or tomb of Rabia Durani stands as a lone soul in the southern part.

- It was Aurangzeb’s long-standing governorship of Aurangabad that the shrine came to exist in the city and is today one of the most famous historical monuments in Maharashtra.

The story of Dilras Banu:

- Dilras Banu, born in the Safavid royal family of Iran, was the daughter of Shahnawaz Khan who was the then viceroy of the state of Gujarat.

- She married Aurangzeb in 1637 thus becoming his first consort and wife.

- Both Aurangzeb and his eldest son, Azam Shah couldn’t bear the loss of the most important woman in their lives.

- It was then in 1668 that Azam Shah ordered for a mausoleum to be built for his beloved mother on the lines of Taj Mahal, which was the resting place of Banu’s mother-in-law and Aurangzeb’s mother, Mumtaz Mahal.

Conservation of the structure:

- The domes and other marble parts of the mausoleum will undergo scientific conservation.

- The domes and minarets of the structure, which are built-in marble, as well as the marble screens inside would undergo scientific conservation.

- The conservation work will involve cleaning and carrying out a chemical treatment to give it a new glow.

What is the historical significance of Nankana Sahib in Pakistan?

Context

Tension mounted in Nankana Sahib in Pakistan and there was outrage in India after a mob, led by the family of a Muslim man who had married a Sikh teenage girl, hurled stones at Gurdwara Janam Asthan, the birthplace of Guru Nanak Dev, and threatened to convert it into a mosque.

About

About/historical significance of Nankana Sahib

- Nankana Sahib is a city of 80,000 in Pakistan’s Punjab province, where Gurdwara Janam Asthan (also called Nankana Sahib Gurdwara) is located.

- The shrine is built over the site where Guru Nanak, the founder of Sikhism, was believed to be born in 1469.

- It is 75 kms to the west of Lahore, and is the capital of Nankana Sahib district.

- The city was previously known as Talwandi, and was founded by Rai Bhoi, a wealthy landlord.

- Rai Bhoi’s grandson, Rai Bular Bhatti, renamed the town ‘Nankana Sahib’ in honour of the Guru. ‘Sahib’ is an Arabic-origin epithet of respect.

Other information

- Besides Gurdwara Janam Asthan, Nankana Sahib has several important shrines, including Gurdwara Patti Sahib, Gurdwara Bal Leela, Gurdwara Mal Ji Sahib, Gurdwara Kiara Sahib, Gurdwara Tambu Sahib — all dedicated to stages in the life of the first Guru.

- There is also a Gurdwara in memory of Guru Arjan (5th Guru) and Guru Hargobind (6th Guru).

- Guru Hargobind is believed to have paid homage to the town in 1621-22.

- The Janam Asthan shrine was constructed by Maharaja Ranjit Singh, after he visited Nankana Sahib in 1818-19 while returning from the Battle of Multan.

- During British rule, the Gurdwara Janam Asthan was the site of a violent episode when in 1921, over 130 Akali Sikhs were killed after they were attacked by the Mahant of the shrine.

- The incident is regarded as one of the key milestones in the Gurdwara Reform Movement, which led to the passing of the Sikh Gurdwara Act in 1925 that ended the Mahant control of Gurdwaras.

- Until Independence, Nankana Sahib’s population had an almost equal number of Muslims, Sikhs, and Hindus, which since Partition has been predominantly Muslim.

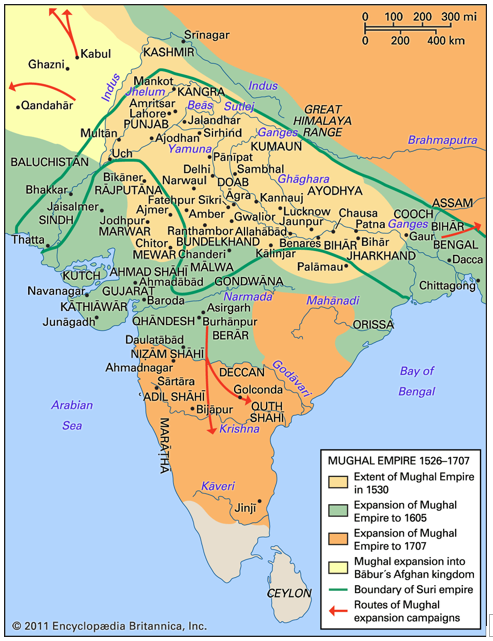

Mughal Empire

- The Mughal Empire at its zenith commanded resources unprecedented in Indian history and covered almost the entire subcontinent. From 1556 to 1707, during the heyday of its fabulous wealth and glory, the Mughal Empire was a fairly efficient and centralized organization, with a vast complex of personnel, money, and information dedicated to the service of the emperor and his nobility.

- Much of the empire’s expansion during that period was attributable to India’s growing commercial and cultural contact with the outside world.

- The 16th and 17th centuries brought the establishment and expansion of European and non-European trading organizations in the subcontinent, principally for the procurement of Indian goods in demand abroad. Indian regions drew close to each other by means of an enhanced overland and coastal trading network, significantly augmenting the internal surplus of precious metals. With expanded connections to the wider world came also new ideologies and technologies to challenge and enrich the imperial edifice.

- The empire itself, however, was a purely Indian historical experience. Mughal culture blended Perso-Islamic and regional Indian elements into a distinctive but variegated whole. Although by the early 18th century the regions had begun to reassert their independent positions, Mughal manners and ideals outlasted imperial central authority. The imperial centre, in fact, came to be controlled by the regions. The trajectory of the Mughal Empire over roughly its first two centuries (1526–1748) thus provides a fascinating illustration of premodern state building in the Indian subcontinent.

- The individual abilities and achievements of the early Mughals—Bbur, Humayun, and later Akbar—largely charted this course. Babur and Humayun struggled against heavy odds to create the Mughal domain, whereas Akbar, besides consolidating and expanding its frontiers, provided the theoretical framework for a truly Indian state.

- Picking up the thread of experimentation from the intervening Sur dynasty (1540–56), Akbar attacked narrow-mindedness and bigotry, absorbed Hindus in the high ranks of the nobility, and encouraged the tradition of ruling through the local Hindu landed elites.

- This tradition continued until the very end of the Mughal Empire, despite the fact that some of Akbar’s successors, notably Aurangzeb (1658–1707), had to concede to contrary forces.

The establishment of the Mughal Empire

Babur

- The foundation of the empire was laid in 1526 by Zahir al-Din Muhammad Babur, a Chagatai Turk (so called because his ancestral homeland, the country north of the Amu Darya [Oxus River] in Central Asia, was the heritage of Chagatai, the second son of Genghis Khan). Babur was a fifth-generation descendant of Timur on the side of his father and a 14th-generation descendant of Genghis Khan. His idea of conquering India was inspired, to begin with, by the story of the exploits of Timur, who had invaded the subcontinent in 1398.

- Babur inherited his father’s principality in Fergana at a young age, in 1494. Soon he was literally a fugitive, in the midst of both an internecine fight among the Timurids and a struggle between them and the rising Uzbeks over the erstwhile Timurid empire in the region. In 1504 he conquered Kabul and Ghazni.

- In 1511 he recaptured Samarkand, only to realize that, with the formidable ?afavid dynasty in Iran and the Uzbeks in Central Asia, he should rather turn to the southeast toward India to have an empire of his own. As a Timurid, Babur had an eye on the Punjab, part of which had been Timur’s possession.

- He made several excursions in the tribal habitats there. Between 1519 and 1524—when he invaded Bhera, Sialkot, and Lahore—he showed his definite intention to conquer Hindustan, where the political scene favoured his adventure.

Conquest of Hindustan

- Having secured the Punjab, Babur advanced toward Delhi, garnering support from many Delhi nobles. He routed two advance parties of Ibrahim Lodi’s troops and met the sultan’s main army at Panipat.

- The Afghans fought bravely, but they had never faced new artillery, and their frontal attack was no answer to Babur’s superior arrangement of the battle line. Babur’s knowledge of western and Central Asian war tactics and his brilliant leadership proved decisive in his victory. By April 1526 he was in control of Delhi and Agra and held the keys to conquer Hindustan.

- Babur, however, had yet to encounter any of the several Afghans who held important towns in what is now eastern Uttar Pradesh and Bihar and who were backed by the sultan of Bengal in the east and the Rajputs on the southern borders.

- The Rajputs under Rana Sanga of Mewar threatened to revive their power in northern India. Babur assigned the unconquered territories to his nobles and led an expedition himself against the rana in person.

- He crushed the rana’s forces at Khanua, near Fatehpur Sikri (March 1527), once again by means of the skillful positioning of troops. Babur then continued his campaigns to subjugate the Rajputs of Chanderi.

- When Afghan risings turned him to the east, he had to fight, among others, the joint forces of the Afghans and the sultan of Bengal in 1529 at Ghagra, near Varanasi. Babur won the battles, but the expedition there too, like the one on the southern borders, was left unfinished.

- Developments in Central Asia and B?bur’s failing health forced him to withdraw. He died near Lahore in December 1530.

Babur’s achievements

- Babur’s brief tenure in Hindustan, spent in wars and in his preoccupation with northwest and Central Asia, did not give him enough time to consolidate fully his conquests in India. Still, discernible in his efforts are the beginnings of the Mughal imperial organization and political culture.

- He introduced some Central Asian administrative institutions and, significantly, tried to woo the prominent local chiefs.

- He also established new mints in Lahore and Jaunpur and tried to ensure a safe and secure route from Agra to Kabul. He advised his son and successor, Humayun, to adopt a tolerant religious policy.

Humayun

- Humayun’s rule began badly with his invasion of the Hindu principality of Kalinjar in Bundelkhand, which he failed to subdue. Next he became entangled in a quarrel with Sher (or Sher) Khan (later Sher Shah of Sur, founder of the Sur dynasty), the new leader of the Afghans in the east, by unsuccessfully besieging the fortress of Chunar (1532).

- Thereafter he conquered Malwa and Gujarat, but he could not hold them. Leaving the fortress of Chunar unconquered on the way, Humayun proceeded to Bengal to assist Sultan Mahmud of that province against Sher Khan.

- He lost touch with Delhi and Agra, and, because his brother Hindal began to openly behave like an independent ruler at Agra, he was obliged to leave Gaur, the capital of Bengal. Negotiations with Sher Khan fell through, and the latter forced Humayun to fight a battle at Chausa, 10 miles southwest of Buxar (Baksar; June 26, 1539), in which Humayun was defeated.

- He did not feel strong enough to defend Agra, and he retreated to Bilgram near Kannauj, where he fought his last battle with Sher Khan, who had now assumed the title of shah. Humayun was again defeated and was compelled to retreat to Lahore; he then fled from Lahore to the Sindh (or Sind) region, from Sindh to Rajputana, and from Rajputana back to Sindh.

- Not feeling secure even in Sindh, he fled (July 1543) to Iran to seek military assistance from its ruler, the ?afavid Shah Tahmasp I.

- The shah agreed to assist him with an army on the condition that Humayun become a Shiite Muslim and return Kandahar, an important frontier town and commercial centre, to Iran in the event of his successful acquisition of that fortress.

- Humayun had no answer to the political and military skill of Sher Shah and had to fight simultaneously on the southern borders to check the sultan of Gujarat, a refuge of the rebel Mughals. Humayun’s failure, however, was attributable to inherent flaws in the early Mughal political organization.

- The armed clans of his nobility owed their first allegiance to their respective chiefs. These chiefs, together with almost all the male members of the royal family, had a claim to sovereignty.

- There was thus always a lurking fear of the emergence of another centre of power, at least under one or the other of his brothers. Humayun also fought against the heavy odds of his opponents’ rapport with the locality.

Sher Shah and his successors

- During Humayun’s exile Sher Shah established a vast and powerful empire and strengthened it with a wise system of administration.

- He carried out a new and equitable revenue settlement, greatly improved the administration of the districts and the parganas (groups of villages), reformed the currency, encouraged trade and commerce, improved communication, and administered impartial justice.

- Sher Shah died during the siege of Kalinjar (May 1545) and was succeeded by his son Islam Shah (ruled 1545–53). Islam Shah, preeminently a soldier, was less successful as a ruler than his father. Palace intrigues and insurrections marred his reign.

- On his death his young son, Firuz, came to the Sur throne but was murdered by his own maternal uncle, and subsequently the empire fractured into several parts.

Restoration of Humayun

- After his return to Kabul from Iran, Humayun watched the situation in India. He had been preparing since the death of Islam Shah to recover his throne.

- Following the capture of Kandahar and Kabul from his brothers, he had reasserted his unique royal position and assembled his own nobles. In December 1554 he crossed the Indus River and marched to Lahore, which he captured without opposition the following February.

- Humayun occupied Sirhind and captured Delhi and Agra in July 1555. He thus regained the throne of Delhi after an interval of 12 years, but he did not live long enough to recover the whole of the lost empire; he died as the result of an accident in Shermandal in Delhi (January 1556). His death was concealed for about a fortnight to enable the peaceful accession of his son Akbar, who was away at the time in the Punjab.

The reign of Akbar the Great

Extension and consolidation of the empire

- Akbar (ruled 1556–1605) was proclaimed emperor amid gloomy circumstances. Delhi and Agra were threatened by Hemu—the Hindu general of the Sur ruler, adil Shah—and Mughal governors were being driven from all parts of northern India. Akbar’s hold over a fraction of the Punjab—the only territory in his possession—was disputed by Sikandar Sur and was precarious. There was also disloyalty among Akbar’s own followers.

- The task before Akbar was to reconquer the empire and consolidate it by ensuring control over its frontiers and, moreover, by providing it with a firm administrative machinery. He received unstinting support from the regent, Bayram Khan, until 1560.

- The Mughal victory at Panipat (November 1556) and the subsequent recovery of Mankot, Gwalior, and Jaunpur demolished the Afghan threat in upper India.

The early years

- Until 1560 the administration of Akbar’s truncated empire was in the hands of Bayram Khan. Bayram’s regency was momentous in the history of India. At its end the Mughal dominion embraced the whole of the Punjab, the territory of Delhi, what are now the states of Uttar Pradesh and Uttaranchal in the north (as far as Jaunpur in the east), and large tracts of what is now Rajasthan in the west.

- Akbar, however, soon became restless under Bayram Khan’s tutelage. Influenced by his former wet nurse, Maham Anaga, and his mother, hamidah Banu Begam, he was persuaded to dismiss him (March 1560).

- Four ministers of mediocre ability then followed in quick succession. Although not yet his own master, Akbar took a few momentous steps during that period.

- He conquered Malwa (1561) and marched rapidly to Sarangpur to punish Adham Khan, the captain in charge of the expedition, for improper conduct. Second, he appointed Shams al-Din Muhammad Atgah Khan as prime minister (November 1561).

- Third, at about the same time, he took possession of Chunar, which had always defied Humayun.

- The most momentous events of 1562 were Akbar’s marriage to a Rajput princess, daughter of Raja Bharmal of Amber, and the conquest of Merta in Rajasthan. The marriage led to a firm alliance between the Mughals and the Rajputs.

- By the end of June 1562, Akbar had freed himself completely from the influence of the harem party, headed by Maham Anaga, her son Adham Khan, and some other ambitious courtiers. The harem leaders murdered the prime minister, Atgah Khan, who was then succeeded by Mun'im Khan.

- From about the middle of 1562, Akbar took upon himself the great task of shaping his policies, leaving them to be implemented by his agents.

- He embarked on a policy of conquest, establishing control over Jodhpur, Bhatha (present-day Rewa), and the Gakkhar country between the Indus and Beas rivers in the Punjab. Next he made inroads into Gondwana. During this period he ended discrimination against the Hindus by abolishing pilgrimage taxes in 1563 and the hated jizyah (poll tax on non-Muslims) in 1564.

Struggle for firm personal control

- Akbar thus commanded the entire area of Humayun’s Indian possessions.

- By the mid-1560s he had also developed a new pattern of king-noble relationship that suited the current need of a centralized state to be defended by a nobility of diverse ethnic and religious groups.

- He insisted on assessing the arrears of the territories under the command of the old Turani (Central Asian) clans and, in order to strike a balance in the ruling class, promoted the Persians (Irani), the Indian Muslims, and the Rajputs in the imperial service.

- Akbar placed eminent clan leaders in charge of frontier areas and staffed the civil and finance departments with relatively new non-Turani recruits.

- The revolts in 1564–74 by the members of the old guard—the Uzbeks, the Mirzas, the Qaqshals, and the Atgah Khails—showed the intensity of their indignation over the change.

- Utilizing the Muslim orthodoxy’s resentment over Akbar’s liberal views, they organized their last resistance in 1580. The rebels proclaimed Akbar’s half-brother, Mirza hakim, the ruler of Kabul, and he moved into the Punjab as their king. Akbar crushed the opposition ruthlessly.

Subjugation of Rajasthan

- Rajasthan occupied a prominent place in Akbar’s scheme of conquest; without establishing his suzerainty over that region, he would have no title to the sovereignty of northern India.

- Rajasthan also bordered on Gujarat, a centre of commerce with the countries of western Asia and Europe. In 1567 Akbar invaded Chitor, the capital of Mewar; in February 1568 the fort fell into his hands.

- Chitor was constituted a district, and ??af Khan was appointed its governor. But the western half of Mewar remained in the possession of Rana Udai Singh.

- Later, his son Rana Pratap Singh, following his defeat by the Mughals at Haldighat (1576), continued to raid until his death in 1597, when his son Amar Singh assumed the mantle. The fall of Chitor and then of Ranthambor (1569) brought almost all of Rajasthan under Akbar’s suzerainty.

Conquest of Gujarat and Bengal

- Akbar’s next objective was the conquest of Gujarat and Bengal, which had connected Hindustan with the trading world of Asia, Africa, and Europe.

- Gujarat had lately been a haven of the refractory Mughal nobles, and in Bengal and Bihar the Afghans under Daud Karrani still posed a serious threat. Akbar conquered Gujarat at his second attempt in 1573 and celebrated by building a victory gate, the lofty Buland Darwaza (“High Gate”), at his new capital, Fatehpur Sikri.

- The conquest of Gujarat pushed the Mughal Empire’s frontiers to the sea.

- Akbar’s encounters with the Portuguese aroused his curiosity about their religion and culture.

- He did not show much interest in what was taking place overseas, but he appreciated the political and commercial significance of bringing the other gateway to his empire’s international trade—namely, Bengal—under his firm control.

- He was in Patna in 1574, and by July 1576 Bengal was a part of the empire, even if some local chiefs continued to agitate for some years more. Later, Man Singh, governor of Bihar, also annexed Orissa and thus consolidated the Mughal gains in the east.

The frontiers

- On the northwest frontier Kabul, Kandahar, and Ghazni were not simply strategically significant; these towns linked India through overland trade with central and western Asia and were crucial for securing horses for the Mughal cavalry. Akbar strengthened his grip over these outposts in the 1580s and ’90s.

- Following hakim’s death and a threatened Uzbek invasion, Akbar brought Kabul under his direct control. To demonstrate his strength, the Mughal army paraded through Kashmir, Baluchistan, Sindh, and the various tribal districts of the region.

- In 1595, before his return, Akbar wrested Kandahar from the ?afavids, thus fixing the northwestern frontiers. In the east, Man Singh stabilized the Mughal gains by annexing Orissa, Koch Bihar, and a large part of Bengal.

- Conquest of Kathiawar and later of Asirgarh and the northern territory of the Nizam Shahi kingdom of Ahmadnagar ensured a firm command over Gujarat and central India. At Akbar’s death in October 1605, the Mughal Empire extended to the entire area north of the Godavari River, with the exceptions of Gondwana in central India and Assam in the northeast.

The state and society under Akbar

- More than for its military victories, the empire under Akbar is noted for a sound administrative framework and a coherent policy that gave the Mughal regime a firm footing and sustained it for about 150 years.

Central, provincial, and local government

- Akbar’s central government consisted of four departments, each presided over by a minister: the prime minister (wak?l), the finance minister (d?w?n, or vizier [waz?r]), the paymaster general (m?r bakhsh?), and the chief justice and religious official combined (?adr al-?ud?r). They were appointed, promoted, and dismissed by the emperor, and their duties were well defined.

- The empire was divided into 15 provinces (subahs)—Allahabad, Agra, Ayodhya (Avadh), Ajmer, Ahmedabad (Ahmadabad), Bihar, Bengal, Delhi, Kabul, Lahore, Multan, Malka, Qhandesh, Berar, and Ahmadnagar.

- Kashmir and Kandah?r were districts of the province of Kabul. Sindh, then known as Thatta, was a district in the province of Multan. Orissa formed a part of Bengal. The provinces were not of uniform area or income.

- There were in each province a governor, a d?w?n, a bakhsh? (military commander), a ?adr (religious administrator), and a q??? (judge) and agents who supplied information to the central government. Separation of powers among the various officials (in particular, between the governor and the d?w?n) was a significant operating principle in imperial administration.

- The provinces were divided into districts (sark?rs). Each district had a fowjd?r (a military officer whose duties roughly corresponded to those of a collector); a q???; a kotw?l, who looked after sanitation, the police, and the administration; a bitikch? (head clerk); and a khaz?ned?r (treasurer).

- Every town of consequence had a kotw?l. The village communities conducted their affairs through pancayats (councils) and were more or less autonomous units.

The composition of the Mughal nobility

- Within the first three decades of Akbar’s reign, the imperial elite had grown enormously. As the Central Asian nobles had generally been nurtured on the Turko-Mongol tradition of sharing power with the royalty—an arrangement incompatible with Akbar’s ambition of structuring the Mughal centralism around himself—the emperor’s principal goal was to reduce their strength and influence.

- The emperor encouraged new elements to join his service, and Iranians came to form an important block of the Mughal nobility.

- Akbar also looked for new men of Indian background. Indian Afghans, being the principal opponents of the Mughals, were obviously to be kept at a distance, but the Sayyids of Baraha, the Bukh?r? Sayyids, and the Kamb?s among the Indian Muslims were specially favoured for high military and civil positions.

- More significant was the recruitment of Hindu Rajput leaders into the Mughal nobility. This was a major step, even if not completely new in Indo-Islamic history, leading to a standard pattern of relationship between the Mughal autocracy and the local despotism.

- Each Rajput chief, along with his sons and close relatives, received high rank, pay, perquisites, and an assurance that they could retain their age-old customs, rituals, and beliefs as Hindu warriors.

- In return, the Rajputs not only publicly expressed their allegiance but also offered active military service to the Mughals and, if called upon to do so, willingly gave daughters in marriage to the emperor or his sons.

- The Rajput chiefs retained control over their ancestral holdings (watan j?g?rs) and additionally, in return for their services, often received land assignments outside their homelands (tankhwa j?g?rs) in the empire. The Mughal emperor, however, asserted his right as a “paramount.” He treated the Rajput chiefs as zamindars (landholders), not as rulers. Like all local zamindars, they paid tribute, submitted to the Mughals, and received a patent of office.

- Akbar thus obtained a wide base for Mughal power among thousands of Rajput warriors who controlled large and small parcels of the countryside throughout much of his empire.

- The Mughal nobility came to comprise mainly the Central Asians (T?r?n?s), Iranians (Ir?n?s), Afghans, Indian Muslims of diverse subgroups, and Rajputs.

- Both historical circumstances and a planned imperial policy contributed to the integration of this complex and heterogeneous ruling class into a single imperial service. The emperor saw to it that no single ethnic or religious group was large enough to challenge his supreme authority.

Organization of the nobility and the army

- In order to organize his civil and military personnel, Akbar devised a system of ranks, or man?abs, based on the “decimal” system of army organization used by the early Delhi sultans and the Mongols.

- The man?abd?rs (rank holders) were numerically graded from commanders of 10 to commanders of 5,000. Although they fell under the jurisdiction of the m?r bakhsh?, each owed direct subordination to the emperor.

- The man?abd?rs were generally paid in nonhereditary and transferable j?g?rs (assignments of land from which they could collect revenues).

- Over their j?g?rs, as distinct from those areas reserved for the emperor (kh?li?ah) and his personal army (a?ad?s), the assignees (j?g?rd?rs) normally had no magisterial or military authority.

- Akbar’s insistence on a regular check of the man?abd?rs’ soldiers and their horses signified his desire for a reasonable correlation between his income and obligations.

- Most j?g?rd?rs except the lowest-ranking ones collected the taxes through their personal agents, who were assisted by the local moneylenders and currency dealers in remitting collections by means of private bills of exchange rather than cash shipments.

Revenue system

- A remarkable feature of the Mughal system under Akbar was his revenue administration, developed largely under the supervision of his famed Hindu minister Todar Mal.

- Akbar’s efforts to develop a revenue schedule both convenient to the peasants and sufficiently profitable to the state took some two decades to implement.

- In 1580 he obtained the previous 10 years’ local revenue statistics, detailing productivity and price fluctuations, and averaged the produce of different crops and their prices.

- He also evolved a permanent schedule circle by grouping together the districts having homogeneous agricultural conditions. For measuring land area, he abandoned the use of hemp rope in favour of a more definitive method using lengths of bamboo joined with iron rings.

- The revenue, fixed according to the continuity of cultivation and quality of soil, ranged from one-third to one-half of production value and was payable in copper coin (d?ms).

- The peasants thus had to enter the market and sell their produce in order to meet the assessment. This system, called ?ab?, was applied in northern India and in Malwa and parts of Gujarat. The earlier practices (e.g., crop sharing), however, also were in vogue in the empire.

- The new system encouraged rapid economic expansion. Moneylenders and grain dealers became increasingly active in the countryside.

Fiscal administration

- All economic matters fell under the jurisdiction of the vizier, assisted principally by three ministers to look separately after the crown lands, the salary drafts and j?g?rs, and the records of fiscal transactions. At almost all levels, the revenue and financial administration was run by a cadre of technically proficient officials and clerks drawn mainly from Hindu service castes—Kayasthas and Khatris.

- More significantly, in local and land revenue administration, Akbar secured support from the dominant rural groups. With the exception of the villages held directly by the peasants, where the community paid the revenue, his officials dealt with the leaders of the communities and the superior landrights holders (zamindars).

- The zamindar, as one of the most important intermediaries, collected the revenue from the peasants and paid it to the treasury, keeping a portion to himself against his services and zamindari claim over the land.

Coinage

- Akbar reformed Mughal currency to make it one of the best known of its time. The new regime possessed a fully functioning trimetallic (silver, copper, and gold) currency, with an open minting system in which anyone willing to pay the minting charges could bring metal or old or foreign coin to the mint and have it struck.

- All monetary exchanges, however, were expressed in copper coins in Akbar’s time. In the 17th century, following the silver influx from the New World, silver rupee with new fractional denominations replaced the copper coin as a common medium of circulation.

- Akbar’s aim was to establish a uniform coinage throughout his empire; some coins of the old regime and regional kingdoms also continued.

Evolution of a nonsectarian state

- Mughal society was predominantly non-Muslim. Akbar therefore had not simply to maintain his status as a Muslim ruler but also to be liberal enough to elicit active support from non-Muslims. For that purpose, he had to deal first with the Muslim theologians and lawyers (?ulam??) who, in the face of Brahmanic resilience, were rightly concerned with the community’s identity and resisted any effort that could encourage a broader notion of political participation.

- Akbar began his drive by abolishing both the jizyah and the practice of forcibly converting prisoners of war to Islam and by encouraging Hindus as his principal confidants and policy makers.

- To legitimize his nonsectarian policies, he issued in 1579 a public edict (ma??ar) declaring his right to be the supreme arbiter in Muslim religious matters—above the body of Muslim religious scholars and jurists.

- He had by then also undertaken a number of stern measures to reform the administration of religious grants, which were now available to learned and pious men of all religions, not just Islam.

- The ma??ar was proclaimed in the wake of lengthy discussions that Akbar had held with Muslim divines in his famous religious assembly ?Ib?dat-Kh?neh, at Fatehpur Sikri.

- He soon became dissatisfied with what he considered the shallowness of Muslim learned men and threw open the meetings to non-Muslim religious experts, including Hindu pandits, Jain and Christian missionaries, and Parsi priests.

- A comparative study of religions convinced Akbar that there was truth in all of them but that no one of them possessed absolute truth.

- He therefore disestablished Islam as the religion of the state and adopted a theory of rulership as a divine illumination incorporating the acceptance of all, irrespective of creed or sect. He repealed discriminatory laws against non-Muslims and amended the personal laws of both Muslims and Hindus so as to provide as many common laws as possible.

- While Muslim judicial courts were allowed as before, the decision of the Hindu village pancayats also was recognized. The emperor created a new order commonly called the D?n-e Il?h? (“Divine Faith”), which was modeled on the Muslim mystical Sufi brotherhood.

- The new order had its own initiation ceremony and rules of conduct to ensure complete devotion to the emperor; otherwise, members were permitted to retain their diverse religious beliefs and practices. It was devised with the object of forging the diverse groups in the service of the state into one cohesive political community.

Akbar in historical perspective

- By 1600 the Mughals in India had achieved a fairly austere and efficient state system, for which Akbar’s genius deserves much credit.

- However, the Mughal system must be studied in the context of broad historical developments of the 16th and 17th centuries.

- Long before Akbar’s schemes, Sher Shah of S?r’s short-lived reforms had included demand for cash payment from the peasants, surveys of agricultural lands and of crops grown, and a reliable, standardized, and high-quality coinage.

- The S?r ruler insisted on a uniform rate for the entire empire, which was certainly a major flaw in contrast to Akbar’s consideration for regional variations.

- It is striking, however, that the chief ?ab? territories under Akbar were largely made up of the provinces already controlled by Sher Shah.

- Another major development of Sher Shah’s brief period—namely, the building of a network of roads to improve the connections already started by B?bur between Hindustan and the great trading routes extending into central and western Asia via Kabul and Kandah?r—foreshadowed in a measure the later imperial edifice and economy.

- By laying a road between Sonargaon (in Bengal) and Attock (near present-day Rawalpindi, Pak.), the S?r ruler had made a first attempt at bringing the economy of Bengal into closer contact with that of northern India.

- The expansion under Akbar followed in logical sequence what had already occurred. The network based on Sher Shah’s routes had extended considerably by 1600. Agra came to be linked not only to Burhanpur but also to Cambay, Surat, and Ahmedabad. Lahore and Multan were now the gateway to Kabul as well as to the ports of the mouth of the Indus.

- The link with Sonargaon became a far more secure control over the ports of Bengal. Many other changes initiated in the late 16th century were to be consolidated only later, in conjunction with further political unification.

The empire in the 17th century

- The Mughal Empire in the 17th century continued its conquest and territorial expansion, with a dramatic increase in the numbers, resources, and responsibilities of the Mughal nobles and man?abd?rs.

- There were also attempts at tightening imperial control over the local society and economy.

- The critical relationship between the imperial authority and the zamindars was regularized and generally institutionalized through thousands of sanads (patents) issued by the emperor and his agents.

- These centralizing measures imposed increasing demands upon both the Mughal officials and the local magnates and therefore generated tensions expressed in various forms of resistance. The century witnessed the rule of the three greatest Mughal emperors: Jah?ng?r (ruled 1605–27), Shah Jah?n (1628–58), and Aurangzeb (1658–1707). The reigns of Jah?ng?r and Shah Jah?n are noted for political stability, brisk economic activity, excellence in painting, and magnificent architecture.

- The empire under Aurangzeb attained its greatest geographic reach; however, the period also saw the unmistakable symptoms of Mughal decline.

- Political unification and the establishment of law and order over extensive areas, together with extensive foreign trade and the ostentatious lifestyles of the Mughal elites, encouraged the emergence of large centres of commerce and crafts.

- Lahore, Delhi, Agra, and Ahmedabad, linked by roads and waterways to other important towns and the key seaports, were among the leading cities of the world at the time.

- The Mughal system of taxation had expanded both the degree of monetization and commodity production, which in turn promoted a network of grain markets (mand?s), bazaars, and small fortified towns (qa?bahs), supplied by a highly differentiated peasantry in the countryside.

- Increasing use of money was illustrated, in the first place, by the growing use of bills of exchange (hund?s) to transfer revenue to the centre from the provinces and the consequent meshing of the fiscal system with the financial network of the money changers (?arr?fs; commonly rendered shroff in English) and, second, by the increasing interest of and even direct participation by the Mughal nobles and the emperor in trade.

- Thatta, Lahore, Hugli, and Surat were great centres for such activity in the 1640s and ’50s. The emperor owned the shipping fleets, and the governors advanced funds to merchants from state treasuries and the mints.

- The shift in the attitude toward trade in the course of the 17th century owed a good deal to the growing Iranian influence in the Mughal court. The Iranians had a long tradition of combining political power and trade.

- Shah ?Abb?s I had espoused greater state control of commerce. Because the contemporary Muslim empires—including the Mughals, the ?afavids, and the Ottomans—were conscious of one another as competitors, mutual borrowings and emulations were more frequent than the chroniclers would indicate.

Jah?ng?r

- Within a few months of his accession, Jah?ng?r had to deal with a rebellion led by his eldest son, Khusraw, who was reportedly supported by, among others, the Sikh Guru Arjun.

- Khusraw was defeated at Lahore and was brought in chains before the emperor.

- The subsequent execution of the Sikh Guru permanently estranged the Sikhs from the Mughals Khusraw’s rebellion led to a few more risings, which were suppressed without much difficulty.

- Shah ?Abb?s I of Iran, taking advantage of the unrest, besieged the fort of Kandah?r (1606) but abandoned the attack when Jah?ng?r promptly sent an army against him.

Submission of Mewar

- Jah?ng?r’s most significant political achievement was the cessation of the Mughal-Mewar conflict, following three consecutive campaigns and his own arrival in Ajmer in 1613.

- Prince Khurram was given the supreme command of the army (1613), and Jah?ng?r marched to be near the scene of action.

- The Rana Amar Singh then initiated negotiations (1615).

- He recognized Jah?ng?r as his suzerain, and all his territory in Mughal possession was restored, including Chitor—although it could not be fortified.

- Amar Singh was not obliged to attend the imperial court, but his son was to represent him; nor was he required to enter into a matrimonial alliance with the Mughal royal family.

- Further, the Rajput rulers of Kangra, Kishtwar (in Kashmir), Navanagar, and Kutch (Kachchh; in western India) accepted the Mughal supremacy. Bir Singh Bundela was given a high rank, and a Bundela princess entered the Mughal harem. Also significant was the subjugation of the last Afghan domains in eastern Bengal (1612) and Orissa (1617).

Developments in the Deccan

- Toward the last years of Akbar’s reign, the Ni??m Sh?h?s of Ahmadnagar in the Deccan had engaged the attention of the emperor considerably.

- The main objective of his intervention in Ahmadnagar was to gain Berar, which had been recently acquired by Ahmadnagar from Khandesh, and Balaghat, which had been a bone of contention between Ahmadnagar and Gujarat.

- By 1596 Berar was conquered and Ahmadnagar had accepted Mughal suzerainty. However, the issue of a clearly defined frontier could not be resolved, and Mughal attacks continued.

- Under Jah?ng?r the rise of Malik ?Amb?r, a Habshi (Abyssinian) general of unusual ability, at the Ahmadnagar court and his alliance with the ??dil Sh?h?s of Bijapur cemented a united front of the Deccan sultanates and initially forced the Mughals to retreat.

- At this time the Marathas also had emerged as a force in the Deccan. Jah?ng?r appreciated their importance and encouraged many Marathas to defect to his side (1615).

- Later, two successive Mughal victories against the combined Deccani armies (1618 and 1620) restrained the Habshi general.

- However, the Deccan expedition remained unfinished as a result of the rise to power of the emperor’s favourite queen, N?r Jah?n, and her relatives and associates.

- The queen’s alleged efforts to secure the prince of her choice as successor to the ailing emperor resulted in the rebellion of Prince Khurram in 1622 and later of Mah?bat Khan, the queen’s principal ally, who had been deputed to subdue the prince.

Rebellion of Khurram (Shah Jah?n)

- After failing to take Fatehpur Sikri in April 1623, Khurram retreated to the Deccan, then to Bengal, and from Bengal back again to the Deccan, pursued all the while by an imperial force under Mah?bat Khan. His plan to seize Bihar, Ayodhya, Allahabad, and even Agra failed. At last Khurram submitted to his father unconditionally (1626). He was forgiven and appointed governor of Balaghat, but the three-year-old rebellion had caused a considerable loss of men and money.

Shah Jah?n

- On his accession, Khurram assumed the title Shah Jah?n (ruled 1628–58). Shahry?r, his younger and only surviving brother, had contested the throne but was soon blinded and imprisoned.

- Under Shah Jah?n’s instructions, his father-in-law, ??af Khan, slew all other royal princes, the potential rivals for the throne. ??af Khan was appointed prime minister, and N?r Jah?n was given an adequate pension

The Deccan problem

- Shah Jah?n’s reign was marred by a few rebellions, the first of which was that of Khan Jah?n Lod?, governor of the Deccan. Khan Jah?n was recalled to court after failing to recover Balaghat from Ahmadnagar. However, he rose in rebellion and fled back to the Deccan. Shah Jah?n followed, and in December 1629 he defeated Khan Jah?n and drove him to the north, ultimately overtaking and killing him in a skirmish at Shihonda (January 1631).

- The next rebellion was led by Jujhar Singh, a Hindu chief of Orchha, in Bundelkhand, who commanded the crucial passage to the Deccan. Jujhar was compelled to submit after his kinsman Bharat Singh defected and joined the Mughals.

- His refusal to comply with subsequent conditions led, after a protracted conflict, to his defeat and murder (1634). Unrest in the region persisted.

- The chronic volatility of the Deccan prompted Shah Jah?n to seek a comprehensive solution. His first step was to offer a military alliance to Bijapur, with the objective of partitioning troublesome Ahmadnagar.

- The result was both the total annihilation of the province and the accord of 1636, by which Bijapur was granted one-third of its southern territories.

- The accord reconciled the Deccan states to a pervasive Mughal presence in the Deccan. Bijapur agreed not to interfere with Golconda, which became a tacit ally of the Mughals.

- The treaty limited further Mughal advance in the Deccan and gave Bijapur and Golconda respite to conquer the warring Hindu principalities in the south. Within a span of a dozen years, Bijapuri and Golcondan armies overran and annexed a vast and prosperous tract beyond the Krishna River up to Thanjavur and including Karnataka.

- The Mughals, on the other hand, maneuvered to regain Kandah?r (1638) and consolidated and extended their eastern position on the Assamese border (1639) and also in Bengal, where Shah Jah?n had become involved in a dispute over Portuguese piracy and abduction of Mughal slaves. In 1648 he moved his capital from Agra to Delhi in an effort to consolidate his control over the northwestern provinces of the empire.

- The Mughal attitude of benevolent neutrality toward the Deccan states began to change gradually after 1648, culminating in the invasion of Golconda and Bijapur in 1656 and 1657.

- A factor in this change was the inability of the Mughals to manage the financial affairs of the Deccan. Subsequently, Bijapur was compelled to surrender the Ahmadnagar areas it had received in 1636, and Golconda was to cede to the Mughals the rich and fertile tract on the Coromandel Coast as part of the j?g?r of M?r Jumla, the famous Golconda vizier who had now joined the Mughal service.

- To a great extent Shah Jah?n’s new policy in the Deccan also was propelled by commercial considerations. The entire area had acquired an added value because of the growing importance of the Coromandel Coast as the centre for the export of textiles and indigo.

Central Asian policy

- Following in the footsteps of his predecessors, Shah Jah?n hoped to conquer Samarkand, the original homeland of his ancestors.

- The brother of Em?m Qul?, ruler of Samarkand, invaded Kabul and in 1639 captured Bamiyan, which gave offense to Shah Jah?n. The emperor was on the lookout for an opportunity to move his army to the northwest borders.

- In 1646 he responded to the Uzbek ruler’s appeal for aid in settling an internal dispute by sending a huge army. The campaign cost the Mughals heavily.

- They suffered serious initial setbacks in Balkh, and, before they could recover fully, an alliance between the Uzbeks and the shah of Iran complicated the situation.

- Kandah?r was again taken by Iran, even though the Mughals reinforced their hold over the other frontier towns.

War of succession

- The events at the end of Shah Jah?n’s reign did not augur well for the future of the empire. The emperor fell ill in September 1657, and rumours of his death spread.

- He executed a will bequeathing the empire to his eldest son, D?r?. His other sons, Shuj??, Aurangzeb, and Mur?d, who were grown men and governors of provinces, decided to contest the throne.

- From the war of succession in 1657–59 Aurangzeb emerged the sole victor. He then imprisoned his father in the Agra fort and declared himself emperor.

- Shah Jah?n died a prisoner on Feb. 1, 1666, at the age of 74.

- He was, on the whole, a tolerant and enlightened ruler, patronizing scholars and poets of Sanskrit and Hindi as well as Persian.

- He systematized the administration, but he raised the government’s share of the gross produce of the soil. Fond of pomp and magnificence, he commissioned the casting of the famous Peacock Throne and erected many elegant buildings, including the dazzling Taj Mahal outside Agra, a tomb for his queen, Mumt?z Ma?al; his remains also are interred there.

Aurangzeb

- The empire under Aurangzeb (ruled 1658–1707) experienced further growth but also manifested signs of weakness. For more than a decade, Aurangzeb appeared to be in full control. The Mughals suffered a bit in Assam and Koch Bihar, but they gainfully invaded Arakanese lands in coastal Myanmar (Burma), captured Chittagong, and added territories in Bikaner, Bundelkhand, Palamau, Assam, and elsewhere. There was the usual display of wealth and grandeur at court.

Decline of Mughal

- The period of the Great Mughals, which began in 1526 with Babur’s accession to the throne, ended with the death of Aurangzeb in 1707. Aurangzeb’s death marked the end of an era in Indian history. When Aurangzeb died, the empire of the Mughals was the largest in India. Yet, within about fifty years of his death, the Mughal Empire disintegrated.

- Aurangzeb’s death was followed by a war of succession among his three sons. It ended in the victory of the eldest brother, Prince Muazzam. The sixty five-year-old prince ascended the throne under the name of Bahadur Shah.

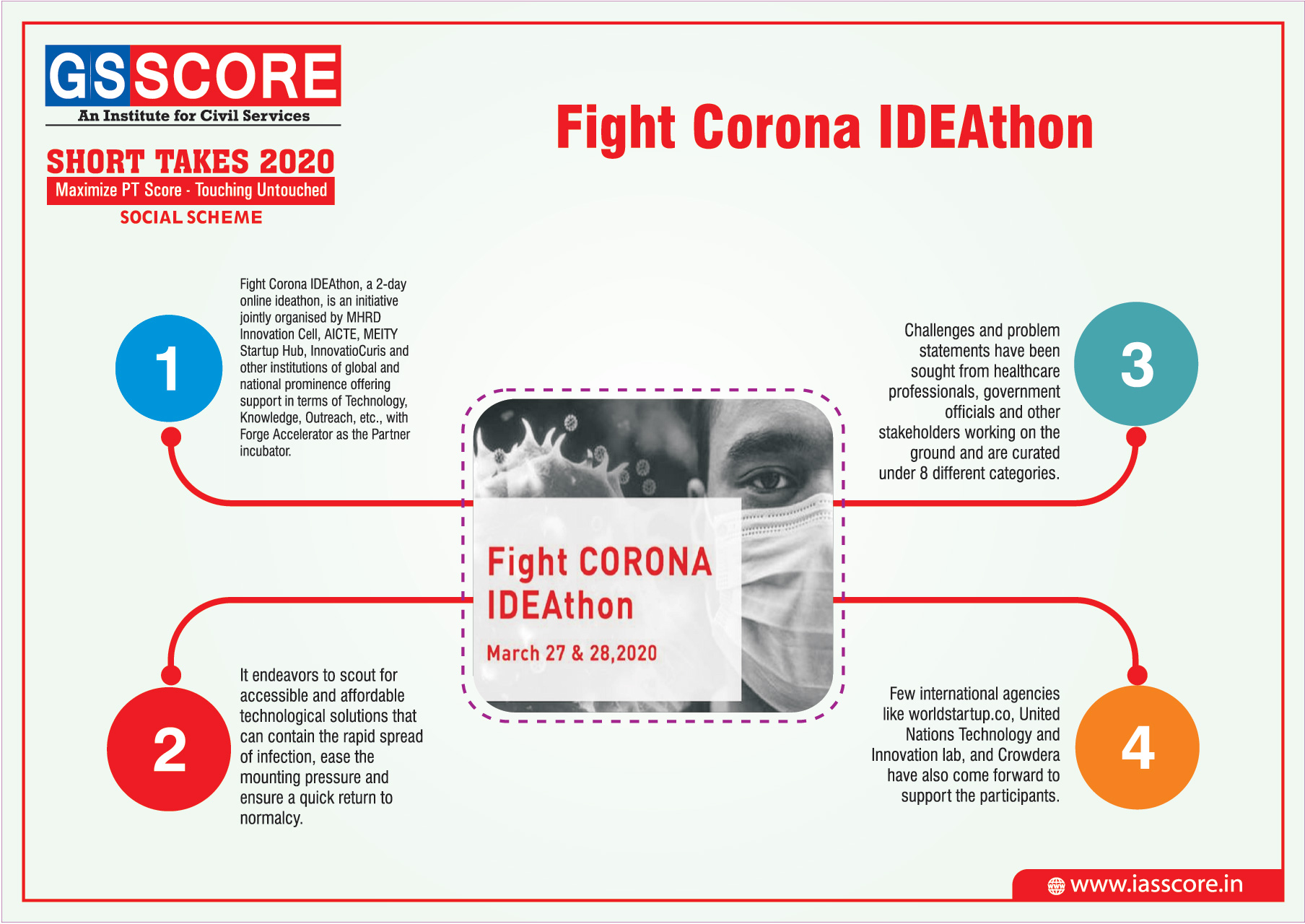

Fight Corona IDEAthon

Online literature festival 2020 organized by VaniPrakashan

Duke Starts Innovative Decontamination of N95 Masks to Help Relieve Shortages

Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Package: Insurance Scheme for Health Workers Fighting COVID-19

Govt Launches “Aarogya Setu” Mobile App

.jpg)