This year we will be celebrating the 75th year of Independence from British Rule which also brings the legacies of partition with it. The freedom was followed by a period of terror in which over 14 million people were forcibly made to relocate and about 2 million lost their lives. The event makes us face up many questions, like why this catastrophic moment came to existence, who was responsible for it, alternatives available to avert it, and many others.

It must be acknowledged that it a not a single entity or a person that can be held responsible for the one the largest migration of people in the century. The British, the Hindu Mahasabha, the Congress, the Muslim League and many others had a significant role to play in its occurrence.

It started with the disguise of trade and ended in August 1947; India gained independence after 200 years of British Rule. It was followed by one of the largest and the bloodiest forced migrations in history. An estimated 1 million people lost their lives. Before British colonisation, the Indian subcontinent was a patchwork of the regional kingdoms known as princely states populated by Hindus, Muslims, Sikhs, Jains, Buddhists, Christians, Parsis and Jews. Each princely state had its own tradition, caste background and leadership.

Background:

- Advent of Foreigners: Starting in the 1500s, a series of European powers colonized India with coastal trading settlements. By the mid-18th century, the English East India Company emerged as the primary colonial power in India. The British ruled some British provinces directly and ruled princely states indirectly. Under the indirect rule, the princely states remained sovereign but made political and financial concessions to the British.

- Conferring Religious Identity: In the 19th century, the British began to categorize Indian by religious identity-a gross simplification of the communities in India. They counted Hindus as “majorities” and all other religious communities as distinct, minorities”, with Muslims being the largest minority. Sikhs were considered part of the Hindu community by everyone but themselves. In the election, people could only vote for candidates of their own religious identity. These practices exaggerated differences, sowing distrust between communities.

- Demand for Two Nation-States: The 20th century began with decades of anti-colonial movements, where Indians fought for independence from Britain. In the aftermath of World War II, under enormous financial strain from the war, Britain finally caved. Indian political leaders had differing views on what an independent India should look like. K Gandhi and J.L Nehru represented the Hindu majority and wanted one united India. Muhammad Ali Jinnah, who led the Muslim minority, thought the rifts created by the colonisation were too deep to repair. Jinnah argued for a two-nation division where Muslims would have a homeland called Pakistan.

- Independence and Partition: Following riots in 1946 and 1947, the British expedited their retreat, planning Indian independence behind closed doors. In June 1947, the British viceroy announced that India would gain independence by August, and be partitioned into Hindu India and Muslim Pakistan- but gave little explanation of how exactly this would happen.

- Mountbatten’s Plan: It clearly outlined the possibility of Partition, the Muslim-majority provinces of Bengal, Punjab, Sind, the North-West Frontier Province (NWFP), and Baluchistan would have the option to either use the existing constitutional assembly to frame their future constitution within a united Indian Union or establish a new and separate constituent assembly.

- Boundary Commission: The commission was appointed by Lord Mountbatten, who was the last viceroy of British India. It consisted of four members from the Indian National Congress and four from the Muslim League and was chaired by Sir Cyril Radcliffe.

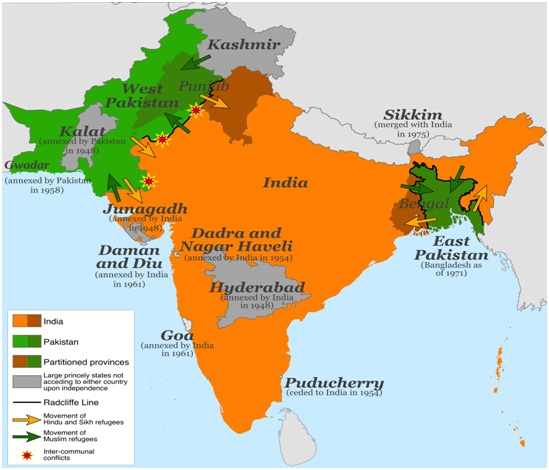

- Using outdated maps, inaccurate census numbers and minimal knowledge of the land, in a mere five weeks, the Boundary Committee drew a border dividing three provinces under direct British rule: Bengal, Punjab and Assam. The border took into account where Hindus and Muslims were majorities, but also factors like location and population percentages.

- Radcliffe’s commission was mainly interested in demarcating the border based on religious demography, other considerations, such as strategic roads and irrigation patterns were also sometimes considered.

- So, if a Hindu majority area bordered another Hindu majority area, it would be included in India-but if a Hindu majority is bordered with a Muslim majority area, it might become part of Pakistan. Princely states on the border had to choose which of the new nations to join, losing their sovereignty in the process.

The Radcliffe Line was the boundary demarcation line between the Indian and Pakistani portions of the Punjab and Bengal provinces of British India. It was named after its architect, Sir Cyril Radcliffe, who, as the joint chairman of the two boundary commissions for the two provinces. - The Boundary Award: The Boundary Commission announced its decision on 17 August 1947, two days after the declaration of independence. Although the award was ready by 12 August, Mountbatten, fearing civil strife, had arranged for its publication only after the British had relinquished constitutional control over India.

- The award assigned 36.36 per cent of the land to accommodate 35.14 per cent of the population to West Bengal, while East Bengal received 63.6 per cent of the land to accommodate 64.85 per cent of the population.

- The provinces of Punjab and Bengal became geographically separated East and West Pakistan. The rest became the Hindu majority in India. In a period of two years, millions of Hindus and Sikhs living in Pakistan left for India. While Muslims living in India fled to villages where their families had lived for centuries. The cities of Lahore, Delhi, Calcutta, Dhaka, and Karachi emptied of all residents and filled with refugees.

- Migration and violence:

- While the Boundary Committee worked on a new map, Hindus and Muslims moving to new areas where they thought to be a part of the religious majority-but they couldn’t be sure. Families divided themselves. Fearing sexual violence, parents sent young daughters and wives to regions they perceived to be safe.

- In the power of vacuum British forces left behind, radicalised militias and local groups massacred migrants. Much of the violence occurred in Punjab, and women bore the brunt of it, suffering rape and mutilation. Around 100,000 women were kidnapped and forced to marry their captors. The problem created by partition went far beyond this immediate deadly aftermath. Many families who made temporary moves became permanently displaced, and borders continued to be disputed.

Analysis:

Looking at Partition:

- Communal representation, the factor that split India at creation in 1947, had a long history going back to 1906 when a demand for it was first made on behalf of Muslims by a delegation led by the Agha Khan to the Viceroy.

- The partition can be seen as a last-minute mechanism by which the Britishers succeeded in securing an agreement over how independence would take place. Breakups are inevitable when coexistence becomes ‘suffocatingly’ impossible.

- After a spectacular success in the 1937 election, Indian National Congress failed to raise the confidence and belief of Muslims in the region they governed. The under-representation of the Muslim community in public services also added to the feeling of being left out.

- Part of the liability rests with the Muslims, as they failed to modernise and were lost in nostalgia. The community lacked reformers like Raja Ram Mohan Roy who campaigned against Sati and Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar who raised his voice for widow’s remarriage.

Issues Related to Boundary Commission:

- Appointment of Cyril Radcliffe was problematic: Radcliffe had neither local knowledge nor any previous association with any kind of boundary-making process.

- Time constraints: The commission has less than 6 weeks to define two international borders in the eastern and western parts of British India. Thus, time constraints severely limited the deliberations about who could be the appropriate members and the rules and the regulations that would guide such a Commission.

- Use of outdated maps: Maps and field surveys were outdated and, in some cases, unavailable. There was no time to bring in or request input from district administrators who had local knowledge of their areas.

- Controversial 1941 Census: it was expected that the Partition was going to be based on religious demography, which made the Census data of 1941 more critical. But Congress representatives to the Commission argued that the census had been conducted at a time when political power and representation depended on an increase in numbers. They claimed that the Muslims had deliberately skewed the census in their favour, bending administrative boundaries to show more Muslim majority areas.

- Unable to solve the “Enclave problem”: Radcliffe award was unable to resolve the case of enclave territories, remnants from Bengal’s Mughal past which now acquired national identities. After 1947, India had 130 enclaves within East Pakistan and Pakistan claimed ninety-five enclaves within Indian territory. The inhabitants of these enclaves became ‘stateless’ people as neither state made efforts to claim them as their own.

In 2015, the historic Land Boundary Agreement (LBA) between India and Bangladesh paved the way for the resolution of the seven-decades-long problem of enclaves between the two countries. About 14,854 residents living in 51 Bangladesh enclaves deep in the territory of India became Indian nationals, and another 922 persons came from Indian enclaves in Bangladesh to Cooch Behar district five years ago.

- Flawed Demarcation: The boundary line zigzagged precariously across agricultural land, cut off communities from their sacred pilgrimage sites, paid no heed to railway lines or the integrity of forests, divorced industrial plants from the agricultural hinterlands where raw materials, such as jute, were grown.

Role of Indian National Congress (INC):

- The core idea that later became the basis of partition was of “Religious Identity”, which was not new in the Indian context. From the beginning, K. Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru rejected this idea and said, “religion does not determine your identity, it does not determine your nationhood, we fought for the freedom of everyone and created a country for everyone.”

- By the end of World War 2, in 1939, Lord Linlithgow, the then Viceroy of India, did not receive much support from the congress and later situation took a different course and eventually Jinnah and Hindu Mahasabha decided not to support the Quit India Movement.

- Winston Churchill, then Prime Minister who was predisposed to the idea of division to manage the situation in India, saw merit in supporting Jinnah over Congress. It may be inferred that Congress either failed to persuade Jinnah to give up the separatist dream, or to convince the British not to help Jinnah take that path.

- In 1942, congress rejected the recommendations of Stafford Cripps Mission, as it was endorsing the idea of partition. Till late 1946, congress opposed the idea of using religion as the determinant for carving nations. The riots took place in West Bengal after the political fallout between Nehru and Jinnah. Jinnah later called for ‘direct action’ to realise the idea of Pakistan. The signs of 'ethnic cleansing' are first evident in the “Great Calcutta Killings” of August 1946. Over 100,000 people were made homeless and more than 4000 people lost their lives.

- Thousands of people lost their lives in the riots in 1946, and this was the time when Congress leaders saw no point fighting over the idea with Jinnah or the Britishers and was the last to reluctantly go along.

Demographic Impacts of Migration:

Literacy:

- The partition-related flows substantially impacted the composition of the literate populations in India and Pakistan. In Pakistan, the out-migrating Hindus and Sikhs were vastly more literate than the resident Muslims.

- The migrants into Pakistani and Bangladeshi districts were significantly more literate than the resident population.

- Outflows in India decreased literacy rates only mildly, while inflows increased literacy rates quite substantially.

- Most of the gains in literacy in India were in Punjab state, while all states in Pakistan show drops in literacy.

- West Bengal gained in literacy while Bangladesh had no districts that gained in literacy. Notably, the minority groups were more educated than the majority in each country.

Occupation:

- Many landless agriculturalists were compelled to seek work. Migrants tended to engage more in all non-agricultural professions. Migrants were significantly less likely to be in agricultural professions for mainly two reasons:

- Such migrants were either already non-property owners, or

- They had to leave lands at the time of migration.

- In the months following Independence, Pakistan lost its bankers, merchants, shopkeepers, entrepreneurs and clerks – the wheels came off the machinery of the state. Jinnah became increasingly panicked, saying that knifing Sikhs and Hindus was equivalent to ‘stabbing Pakistan’.

- Similarly, in India, the sudden disappearance of Muslim railwaymen, weavers and craftsmen, agriculturalists and administrators, brought gridlock to production and trade and crippled the state’s ability to function.

- Large numbers of the incoming refugees arrived with quite different occupational histories and could not or were not qualified to plug the gaps left by those who departed. It can be said that the “migration was a tragedy for the refugees themselves and also a tragedy for the two new states.”

Gender:

- Migrants were indeed more likely to be men. Men were more likely to migrate to more distant districts and larger cities. This is evident from the fact, that some districts in south India received very few migrants, but with a high percentage of men.

- The post-colonial state also upheld traditional gender roles in its treatment of refugees. The social stigma attached to widowhood was reflected in the establishment in Delhi, for example, of a separate refugee colony for young widows.

“Cumulative Impact” of Partition on Migration, Literacy, Gender and Occupation:

- The partition-related flows resulted in an increase in literacy rates in India and a decrease in the percentage of people engaged in agriculture.

- In Pakistan, while incoming migrants tended to raise the literacy rates, out-migrating Hindus and Sikhs (themselves being very literate) tended to reduce total literacy - in sum, there is a decrease in Pakistan’s literacy rate as a result of partition. In addition, these flows led to a decrease in male ratios in India and Pakistan.

Map of the partition of India and Pakistan in 1947

The Refugees of Partition: New states and their Citizens

Refugee: is a person who owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country.

- Both India and Pakistan instituted the “Permit System in 1948” and the “Passport Visa in 1952” that allowed certain groups of refugees to enter and prevented others from returning home. By ordinance, a permit system was instituted, and prospective migrants were scrutinized and filtered, ending the mass movement of migrants from then-West Pakistan to India.

Permit System in 1948: On 19 July 1948, the government of the new nation of India ceased allowing the free transit of migrants from the new nation of Pakistan. This system provided that a person who is desiring to return to India with an intention to permanently reside was required to get a separate permit.

- Migration and property became nationalized: The act of moving from one state to another meant the relinquishing of one’s property, indicating a sort of declaration of intent, a ‘natural’ inclination towards the other nation. Interestingly, the Permit system was not put in operation in the eastern sector with both governments preferring to keep that border open until the establishment of the Passports in 1952.

- Role of Intermediary Officials: They were entrusted with the implementation of laws and were often located at a distance from central and higher authorities and had substantial discretionary powers in the districts and town to interpret the law as they saw fit. The policies and legislation which meant to be non-discriminatory on paper often followed a discriminatory path when implemented by some of the officials.

- Large Influx of Refugees: The national capital of Delhi witnessed a huge inflow of refugees and the entire city of Faridabad had to rehabilitate refugees living in appalling conditions in the temporary camps. The project was close to Nehru and the enterprises were to be set up on the cooperative model, where the people themselves built the city from the ground up. Similar was the state of Assam where people were coming in from eastern Pakistan.

- Evacuee property had been supplemented by building refugee colonies in existing towns and creating new satellite towns such as Faridabad and Rajpura. The latter development on the GT Road, fifteen miles west of Ambala, was built at the cost of Rs. 20 million. It was termed 'one of the biggest experiments of the Government of India in building a well-planned and simple yet dignified home for refugees'

Citizenship to the Migrants and Concerns of New Minority:

- The act of migration, even if temporary, served to define one’s nationality. It came to be seen as an indication of one’s intent to acquire new citizenship and to relinquish one’s original identity.

- Migration ensured that the same person could be designated an evacuee in one country and a refugee in another. Neither term guaranteed citizenship rights.

- Citizenship Act of 1955: Although the laws defining citizenship came to be established by the Citizenship Act of 1955, ambiguities about who was entitled to Indian citizenship continued and the laws were prone to contextual interpretation with regard to those groups who would become ‘minorities’ within India and Pakistan after 1947.

- The government of India initially allowed citizenship rights to those migrants who officially declared their intention to become citizens of India and later acquired the necessary documentation. Getting one’s name on the electoral rolls was one of the primary ways to ensure subsequent citizenship rights. Such a policy presented two contradictory dilemmas for Indian authorities.

- On the one hand, allowing any migrant to acquire citizenship, could limit its rehabilitation responsibilities towards the refugees.

- On the other hand, the government feared that such a policy might encourage Hindu minorities to opt for migration in such large numbers that would not only create an economic strain but also threaten the secular facade of the Indian State.

- To control the continuing tide of migration, the Indian government has to fix a time limit by which a refugee/migrant had to declare his/her intention to stay in India and declared that inclusion within the electoral rolls would not guarantee automatic citizenship rights.

- L Nehru was against any mass population exchange, recognizing the economic burden such a process would engender. He was of opine that, an exchange of population would ‘upset the economy of India’, and that ‘we will sink as a nation without any resources with a starving and dying population’.

- He also asserted, “All citizens must also on their part not only share in the benefits of freedom but also shoulder the burdens and responsibility that accompany it, and must above all be loyal to India.

- The routine of violence continued for two decades after 1947 and engendered migration across borders both to and from India.

Conclusion: The duality of Independence-Partition points at the inability of the then pollical leadership, which although succeeded in building up nationalist consciousness to force the British to quit India was not enough to integrate Muslims into the nation. This contradictory outcome of the national movement resulted in independence but with partition.

The partition had ruptured the evolution of co-existing communities, historical trajectories took a different course and forced violent state formation. In the absence of it, history could otherwise have taken different paths. More than 70 years later, the legacies of partition remain clear in the subcontinent: in its new political formations and the memories of divided families.

Related Articles