Context

Covid-19 and the response to it in India has forced daily wagers and low-wage workers in urban slums to return to their villages, orchestrating an unprecedented U-turn in migration trends.

Assessing the challenges in absorbing migrant labour returning from urban areas

- Rural India is incapable of absorbing the estimated 23 million interstate and intrastate migrant labour who might return home from urban areas due to the Covid-19 lockdown. This is because the rural economy is already overburdened, excessively dependent on agriculture, and has widespread hidden underemployment. The challenges are as follow:

Hidden unemployment

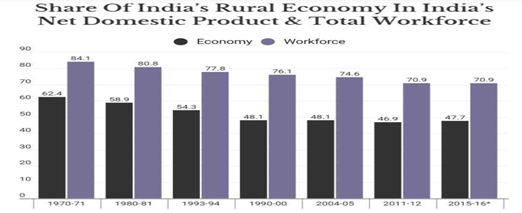

- Contributing less than half – 48% – of India’s net domestic product in 2015-’16, the rural economy supports 70% of India’s population, according to National Account Statistics from 2017 and the government’s latest labour survey from 2017-’18. This creates substandard living conditions in rural areas, with an annual per capita income of Rs 40,928 in 2015-’16, less than half the urban per capita income of Rs 98,435.

- The productivity of each person in rural India is low. About 71% of India’s total workforce is in the rural economy but as the contribution to the economy is 48%, the productivity of the rural workforce is lower than that of the workforce in urban areas.

- The introduction of more capital and technology should improve labour productivity. But in rural areas, labour productivity has instead slightly reduced over the years.

- The productivity gap in 1970-’71 was below 12%, which rose to about 13% in 2017-’18, data from the 2015-’16 national accounts and the 2017-’18 labour survey show. Despite the increase, this gap remains small, implying hidden underemployment. In such a situation, the rural economy cannot gainfully employ returning migrants.

Over-dependence on agriculture

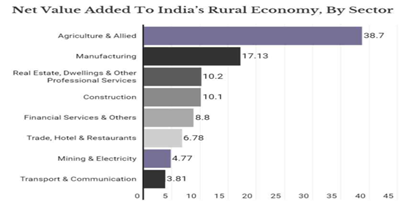

- The rural economy is also over-reliant on agriculture and lacks diversification, due to which it will be unable to create more employment in rural areas. Agriculture is the predominant sector in India’s rural economy, making up the largest part – 38.7% – of the 2015-’16 net domestic product .

- Ordinarily, manufacturing, comprising 17% of the net domestic product, and construction, comprising 10%, could help absorb the additional labour in rural areas. But in India, although the share of manufacturing in the rural economy has grown to 17% in 2015-’16 from 5.9% in 1970-’71, and the sector itself has grown at an average rate of 15% between 2005 and 2012, it is not large enough to absorb returning migrants.

Stressed economy

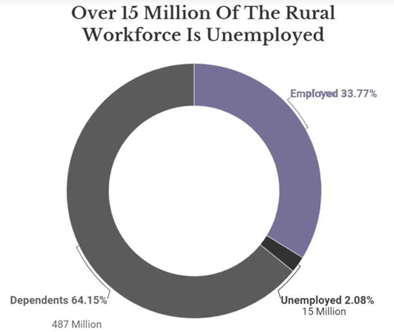

- Just over a third, or 36%, of the rural population was working or available for work in 2017-’18, according to calculations from the Periodic Labour Force Survey, based on the 365 days preceding the survey. The remaining 64% of the population–mostly children below the age of 14 years and the elderly–is dependent on them.

- Of those who are part of the labour force, 5.8% – 15.8 million – were unemployed for the major part, according to calculations based on data from the Periodic Labour Force Survey.

- Of those who were employed, only about 4.6% had regular salaries while about 90% did not even have a job contract. Most of the rural workforce does not have social security benefits that are available to organised sector workers.

Poorer states

- Those states that have higher out-migration also have higher unemployment, so that their economies will find it even more difficult to absorb returning migrants. Of all interstate migrants in India, 23% are from Uttar Pradesh and 14% from Bihar, according to data from Census 2011. The rural unemployment rate in these two states – 7% in Bihar and 6% in UP – is higher than the Indian average of 5.8%, according to the Periodic Labour Force Survey.

- Uttar Pradesh makes up about 15% of India’s total rural unemployment and Bihar 10%. These two states are also marred by a high rate of rural poverty – 37% of India’s poor live in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar.

- Besides Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, rural labour from other states such as West Bengal, Madhya Pradesh and Odisha migrates to Maharashtra, Gujarat, Punjab and other states for employment. Most of these source states are poor: 35% of the rural population lives below the poverty line in Odisha, 35.7% in Madhya Pradesh, and 22% in West Bengal.

Stimulus package to absorb surplus workforce in rural market

- The stimulus package under the Atmanirbhar Bharat initiative and allocations under other programmes for infrastructure development is expected to absorb a good part of regular and surplus (including returnee migrants) workforce in the rural market.

- The MSME sector, with a high capacity to accommodate labour, and having received a special government package, should take care of the skilled and semi-skilled workforce.

- Restarting the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme, more commonly known as MGNREGS- measure announced for Covid-19 relief – could help bring the rural economy back on track, but will not be enough to solve the reverse migration problem.

- There is also a continued need for social safety net programmes, such as the PDS to focus on the vulnerable sections of rural society. In this context, the “One Nation, One Ration card” policy can particularly be effective in enhancing food security of the most vulnerable migrants.

How rural growth can reverse migration?

- Rising urban demand for diverse foods can be tapped by smallholders to fuel rural employment growth.

- Demand for high-quality food is rising, and a small farm’s income growth potential in producing diverse crops is higher than that of primary staples. Also, bringing post-harvest processing and value addition operations closer to food production centres can enhance employment opportunities.

- ICT and e-markets can further enhance farmer participation in high-value markets, where educated rural youth can manage smart technologies and management practices. Agri-tech start-ups may be incentivised to strengthen e-commerce and delivery linkages in rural landscapes.

- One nation, one market” policies, could pave the way for enhancing the market size and ensuring more stable food prices.

- MGNREGA is a demand-driven scheme that guarantees wage employment to volunteers prepared to do unskilled manual work. That notwithstanding, there is a provision for “unemployment allowance” in case employment cannot be provided. Awareness campaigns and civil society engagements may prove helpful in informing migrants.

- If productive assets like improved land, water harvesting structures, etc, are created in mission mode, it would, directly and indirectly, help rebuild the rural economy.

- A transparent land-lease market, backed by an institutional framework, would boost investments in the rural economy and increase the access of lessees to government entitlements like PM-KISAN, insurance/credit, etc.

Conclusion:

Unlike many other sectors, agriculture has potential to revive the pandemic-hit economy. Spurring the rural economic growth can become the saviour for the situation and taking care of the most vulnerable. Critical data on the migrant workforce would facilitate effective policymaking. The state of Madhya Pradesh has shown the way ahead by surveying returnee migrants and mapping their skillsets. Hence, creation of such databases across the country while linking to the Aadhaar stack to facilitate inclusive and affirmative government actions.

India’s population is expected to be more feminine in 2036