Context

Recently, National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) published its annual ‘Crime in India’ report providing statistics on crimes committed in India in 2020.

About

- In the last three years, according to its data, 418,385 crimes against children were recorded.

- Of these, child sex abuse offences under the Protection of Children against Sexual Offences (POCSO) Act, 2012, alone accounted for 134,383 – or roughly one third – of the recorded incidents.

- Every third crime registered against a child is under POCSO, one would expect the NCRB to collect and present accurate and detailed data related to POCSO offences.

- 3 In 5 People Trafficked Were Children. However, between 2011 and 2018, the total number of cases of human trafficking recorded in the country, according to NCRB reports, was 35,983.

- This means, only 0.2% of all survivors of human trafficking received the compensation announced by the government in the last eight years.

What are the constitutional and legal provisions related to human trafficking in India?

- Trafficking in Persons or Persons is prohibited under the Constitution of India under Article 23 (1).

- The Immoral Traffic (Prevention) Act, 1956 (ITPA) is the primary law to prevent human trafficking for the purpose of sexual exploitation.

- The Criminal Law (Amendment) Act 2013 came into force when Section 370 of the Indian Penal Code was replaced by Sections 370 and 370A IPC which provides comprehensive measures to combat the risk of human trafficking including child trafficking in any form including- physical abuse or any other form of sexual exploitation, slavery, servitude, or forced mutilation.

- The Child Sexual Offenses Protection Act (POCSO), 2012, which came into effect on November 14, 2012, is a special law to protect children from abuse and exploitation.

- It provides accurate definitions of various types of sexual harassment, including incest and non-sexual assault, sexual harassment.

- There are other specific laws enacted regarding the trafficking of women and children,

- The Prohibition of Child Marriage Act, 2006

- the Bonded Labour System (Abolition) Act, 1976

- Child Labour (Prohibition and Regulation) Act, 1986

- Governments have also enacted laws to address this issue. (E.g. Punjab Prevention of Trafficking in Persons Act, 2012).

Data gaps and inaccuracy report:

- The World Vision report said existing available data from CSE's second human trafficking sources were not available as the victims were hidden individuals and there was no effective screening method to track them.

- Estimates for women and girls at CSE vary from 70,000 to 3 million in India.

- NCRB data reveals only reported cases that are not all reported cases, simply because the parents are reluctant to report or the parents themselves are involved. "

- Insufficient data hinders the work of organizations such as World Vision India.

- The work of government agencies is also suffering — a lack of data makes it difficult to locate and identify high-risk areas, making it difficult to focus on prevention and law enforcement efforts.

- The lack of data makes it very difficult to track the severity of the situation and small numbers indicate that there is no immediate problem.

- There is a global data gap in trafficking reporting. It is not easy for victims of trafficking to report because most of them come from some of the most vulnerable and disadvantaged sections of society but many details are lost due to the lack of an integrated data collection system.

- Integrated reporting and the use of digital information by the police can lead to a more accurate integration of national data.

- If the first information reports and case papers are included in the digital system, there will be more accurate reports of trafficking crimes.

The problem of clubbing offences in the NCRB report

- The highest class of offences registered against children, as per the NCRB data, are those related to kidnapping and abduction, punishable under the Indian Penal Code.

- For these offences, the NCRB provides data under ten heads, including missing children deemed as kidnapped, kidnapping for ransom, kidnapping and abduction to compel minor girls for marriage and so on.

- All of these are distinct offences covered by different provisions of law and punished differently.

- For policymakers to understand trends in these offences, design counter strategies and direct resources, such granular data is useful.

- But when it comes to the POCSO Act, which prescribes only a select few offences, different offences are clubbed together for the purpose of reporting, rendering the data unintelligible and devoid of purpose.

|

For instance

The difference between penetrative sexual assault and its ‘aggravated’ version is not simply a function of the degree of penetration or harm caused; the legislature, in all its wisdom, has categorized certain circumstances, or an assault committed by certain people, to be of an aggravated nature. |

- In the same manner clubbing of cases from Section 17-22 deprives citizens of insights related to two important protections afforded under the POCSO Act.

- Section 21 punishes the non-reporting of an offence and can be invoked against the family of a child for trying to suppress incidents of sexual assault by family members or against the police for refusing to record an offence under POCSO.

- Section 22 makes it punishable to falsely implicate a person under any POCSO offence.

Both these sections, again, are conceptually different and serve unique purposes – discouraging the suppression of offences and discouraging false cases respectively.

- Clubbing them together defeats the purpose of drawing a distinction between these two offences.

How Clubbing POCSO offences makes the data irrelevant?

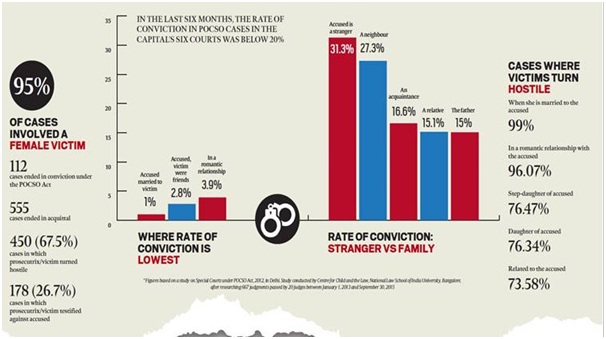

- A 2018 study conducted by the Centre for Child and the Law at NLSIU, Bangalore looked at the judgments of special courts established under POCSO in five states.

- In Maharashtra, aggravated charges were not invoked by the police in 51% of cases where the facts revealed aggravated circumstances.

- For Andhra Pradesh, this was seen in 35% of cases where aggravated charges were warranted. Similar trends were observed for Karnataka and Assam.

- The study also noted that, as a precaution, the police may sometimes invoke both simple and aggravated charges in cases where the facts are not clear.

- But by clubbing the reporting of the simple and aggravated sections, the NCRB data makes it impossible to decipher whether the police are clubbing offences while lodging complaints or if aggravated charges are not being invoked where they should be.

- This also becomes problematic when another NCRB dataset is considered, that of the offender’s relationship to the child victims under POCSO.

- According to this dataset, the offender is known to the child in 96% of cases under Sections 4 and 6 combined. In 51% of cases, the offender is a family member, friend, employer or a known person.

- This is significant because assault by a person who is related to the child through blood, adoption, marriage or shares a household or is part of the management or staff of an institution where the child studies or resides and so on is an aggravated offence under POCSO.

- This means that the majority of cases reported under Sections 4 and 6 would warrant invoking aggravated charges. However, because the NCRB clubs offences, it is not possible to determine if this is happening.

- In another instance, the NCRB record shows only 244 cases under POCSO in Rajasthan in 2020, of which a considerable majority – 180 – fell under Sections 17-22.

- Due to such clubbing, it is impossible to determine whether these cases pertain to the non-reporting of offences or false complaints.

What should be done to prevent Child Abuse?

- Raising awareness, providing sexual abuse prevention education and building child-safe cultures

- Supporting and empowering victims and survivors

- Enhancing responses to children who display sexual behaviours that are harmful to themselves or others

- Offender prevention and intervention

- Improving the evidence base on what works in child sexual abuse prevention and supporting survivor recovery and healing.

Way forward

Even with its limitations, the NCRB data is referred to by policymakers and informs policy decisions. It is imperative that it continues to improve and become more robust. As for POCSO cases, the NCRB must avoid clubbing offences or change its format so as to encourage the police to not club offences and provide granular data on all cases under distinct sections. This will enable the research and analysis of trends and help in identifying operationalization issues that need to be addressed. The discrepancies must be noted and responded to as soon as possible to avoid questions being raised on the veracity and efficacy of data.

In the fight against the growing menace of child sex abuse, the availability of accurate and timely data could be immensely useful. The national strategy provides a framework for reducing child sexual abuse, empowering survivors and their families, and improving our responses to those who have been harmed.