The Supreme Court of India has asked Parliament to amend the Constitution to strip Legislative Assembly Speakers of their exclusive power to decide whether legislators should be disqualified or not, under the Anti-Defection Law.

Issue

Context

The Supreme Court of India has asked Parliament to amend the Constitution to strip Legislative Assembly Speakers of their exclusive power to decide whether legislators should be disqualified or not, under the Anti-Defection Law.

What is ‘Anti-Defection Law’?

- The 'anti-defection law' was passed through an Act of Parliament in 1985.

- Passed as the 52nd Amendment Act, it added the law as the 10th Schedule of the Constitution of India. Articles 102 (2) and 191 (2) deals with anti-defection.

- Aaya Ram Gaya Ramwas a phrase that became popular in Indian politics after a Haryana MLA Gaya Lal changed his party thrice within the same day in 1967.

- The anti-defection law sought to prevent such political defections which may be due to reward of office or other similar considerations.

- It lays down the process by which legislators may be disqualified on grounds of defection by the Presiding Officer of a legislature based on a petition by any other member of the House.

- A legislator is deemed to have defected if:

- He either voluntarily gives up the membership of his party

- He disobeys the directives of the party leadership on a vote

- This implies that a legislator defying (abstaining or voting against) the party whip on any issue can lose his membership of the House.

- The law applies to both Parliament and state assemblies.

- Exception:

- There are few exceptions in the law. However, this exception is applicable only if not less than two-thirds of the members of the party in the House have emerged to the merger.

- A person shall not be disqualified if his original political party merges with another, and:

- He and other members of the old political party become members of the new political party, or

- He and other members do not accept the merger and opt to function as a separate group.

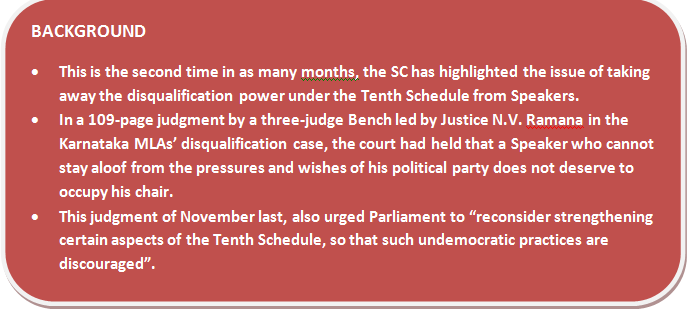

SC on the issue:

- A three-judge Bench led by Justice Rohinton F. Nariman questioned why a Speaker, who is a member of a particular political party and an insider in the House, should be the “sole and final arbiter” in the disqualification of a political defector.

- “It is time Parliament had a rethink on whether disqualification petitions ought to be entrusted to a Speaker as a quasi-judicial authority when such Speaker continues to belong to a particular political party either de jure or de facto,”.

- For that matter, it asked why disqualification proceedings under the Tenth Schedule (anti-defection law) should be kept in-house and not be given to an “outside” authority.

- Even the final authority for removal of a judge is outside the judiciary and in Parliament.

- Replacing Speaker with tribunal: Disqualification petitions under the Tenth Schedule should be adjudicated by a mechanism outside Parliament or the Legislative Assemblies. The court suggested a permanent tribunal headed by a retired Supreme Court judge or a former High Court Chief Justice to determine the fate of an MP or an MLA who has switched sides for money and power.

Power of Speaker under Tenth Schedule:

- The Speaker is the head of the Lok Sabha Secretariat which functions under her ultimate control and direction.

- Under the provisions of the Tenth Schedule to the Constitution of India (para-6) Presiding Officer of the concerned House is the sole and final authority to determine the alleged question of disqualification on the ground of defection.

- On the other hand, to determine the question as to whether the Speaker/Chairman of a House has indeed defected, the Tenth Schedule provides for a procedure according to which a member of concerned House is elected on an ad-hoc basis to determine the alleged question of disqualification on the ground of defection.

- After Kihoto Hollohan versus Zachilhu case (1993), the Supreme Court declared that the decision of the presiding officer is not final and can be questioned in any court.

- It is subject to judicial review on the grounds of malafide, perversity, etc.

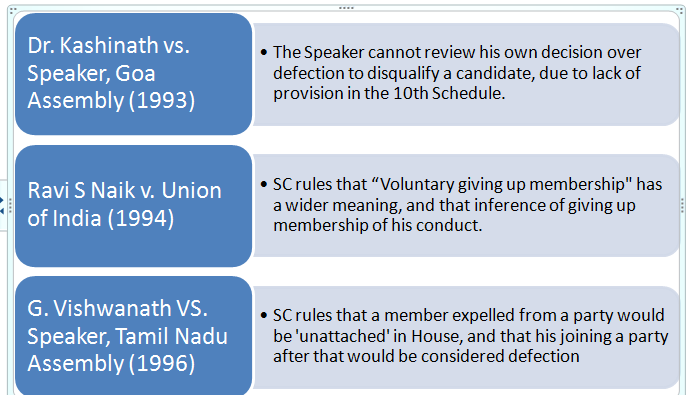

Major cases on the Anti-Defection Law:

Anti-Defection Law in other countries:

- Among the Commonwealth countries, anti-defection law is prevalent in 23 nations.

- The anti-defection law in Bangladesh, Kenya, South Africa and Singapore disqualifies a legislator on his ceasing to be a member of the party or when he is expelled.

- In the United Kingdom Parliament, a member is free to cross over to the other side, without being daunted by any disqualification law.

- In the United States, Canada, and Australia, there is no restraint on legislators switching sides.

The need for amendment:

The Anti-Defection Law has several loopholes that obstruct the democratic functioning of the electoral process.

- Controversial: The law has invited controversy from the beginning, being challenged in court multiple times. Soon after its introduction, it was taken to the SC for being “unconstitutional.”

- Misuse: Though it curbed the free movement of legislators between parties, its loopholes still enabled the misuse of its provisions for partisan ends. In 1987, paragraphs 6 and 7 of the Tenth Schedule came into question because they did not allow room for judicial review of cases of defection.

- Partisan Speakers: The power to decide petitions seeking disqualification of lawmakers under the anti-defection law i.e. the Tenth Schedule rests with the Speaker. The speaker necessarily belongs to a political party, and therefore, their judgment cannot be impartial. This negates the spirit of the Anti-Defection Law.

- Delay in duty: In most cases, Speakers have failed to act in an impartial manner, forcing the top court to intervene from time to time.

- Pressure & criticism: The anti-defection law has put the entire onus on the Speaker in the matters related to disqualification of members of the Legislative House. Even if the Speaker is impartial, he faces undue pressure and criticism.

Benefits of amendment:

- More power: An amendment will give teeth to provisions in the Tenth Schedule, which are vital to the proper functioning of democracy.

- Unbiased & quick decision: Setting up of a permanent tribunal will ensure that such disputes are decided both swiftly and impartially.

- Improving the structure: For now, tightening and cleaning up the anti-defection law is among the most urgently needed reform. It is essential to tend to the health of the world’s largest democracy.

- To combat the constitutional crisis: Despite the anti-defection law, the phenomenon still prevails (defections in Karnataka, Goa). These incidents have raised questions on the validity of the anti-defection law and its application. Reforms are needed to combat constitutional crises.

In the world’s largest democracy, political changes will keep happening and the country cannot escape from it. Therefore, it is essential to ponder upon the politics of defection not only because it leads to a constitutional crisis but also it makes the democracy of India more vulnerable and weak. It is time to re-evaluate whether the present law of anti-defection can ensure political ethics or morality.