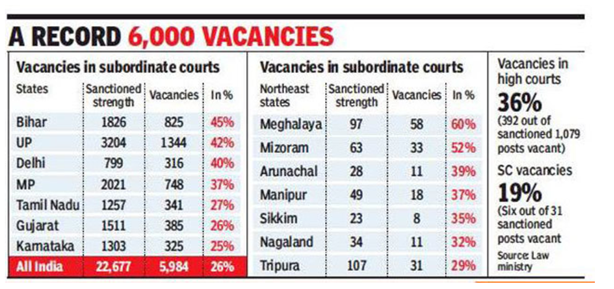

The Supreme Court pulled up various State governments and the administrative side of the High Courts for delay in filling vacancies in subordinate judicial services.

Issue

Context:

- The Supreme Court pulled up various State governments and the administrative side of the High Courts for delay in filling vacancies in subordinate judicial services.

- India has 19 judges per 10 lakh people on an average, according to a Law Ministry data which also states that the judiciary faces a combined shortage of over 6,000 judges, including over 5,000 in the lower courts itself.

Background:

- According to the Constitution, district judges are appointed by the Governor in consultation with the High Court.

- Other subordinate judicial officers are appointed as per rules framed by the Governor in consultation with the High Court and the State Public Service Commission.

- There is not much change since 1987 when the Law Commission had recommended increase in the number of judges from 10 judges per 10 lakh people to 50.

- The Supreme Court had laid down guidelines in 2007 for making appointments in the lower judiciary within a set time frame.

- A study released last year by the Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy revealed that the recruitment cycle in most States far exceeded the time limit prescribed by the Supreme Court. This time limit is 153 days for a two-tier recruitment process and 273 days for a three-tier process.

Analysis

Reasons behind vacancy:

- Poor infrastructure is available for judiciary from courtrooms to residences for judges which is used to facilitate judicial proceedings.

- State Public Service Commission (SPSC) do not recruit enough staff to assist the judges.

- Tardiness in the process of SPSCs like calling for applications, holding recruitment examinations and declaring the results.

- Lack of funds to pay and accommodate the newly appointed judges and magistrates.

- State governments do not employ enough efforts to build courts or identify space for them. There are procedural delays on their part. The MoP gives six weeks to state governments to approve the recommendations and send its suggestions to the Law Ministry.

- Slow motion on part of judiciary. The provision of MoP outlines that when a permanent vacancy is expected to arise in any year in the office of a Judges, the Chief Justice will as early as possible but at least six months before the date of occurrence of the vacancy communicate to the Chief Minister of the State his views as to the persons to be selected for appointment. But this provision remains only on paper.

- A lot of rejections are there of the names the collegium(s) sends to fill vacancies. Normally, there are at least 33% rejections by the Apex Court collegium.

- Close coordination between the High Courts and the State Public Service Commission is missing which is required for smooth and time-bound process of making appointments.

- Coordination between 2 organs of state, that is, judiciary and executive is also a problem. For example long standoff between the government and the judiciary over setting up of National Judicial Appointments Commission (NJAC), a constitutional body proposed by the government to replace the present Collegium system of appointing judges and a continuing debate on Memorandum of Procedure (MoP).

- Judiciary is unable to attract best talent. The brighter law students do not join the state judicial services because they have less career progression and lawyers with a respectable Bar practice sometimes do not want to become an additional district judge and deal with the hassles of transfers and postings.

Consequences:

- Subordinate courts perform the most critical judicial functions: It affect the life of a common man- conducting trials, settling civil disputes, and implementing the bare bones of the law.

- Large pendency of cases: Of the total 3 crore cases pending at different courts, 27.8 lakh cases are piled up in subordinate courts and 4.3 lakh in 10 high courts of India. The pendency in lower courtswith 22.57 lakh cases pending for more than 10 years and about 25% of cases pending for over 5 years is a matter of concern.

- The Quality of the subordinate judiciary: It is average and by extension at least one-third of high court judges elevated from the subordinate judiciary are also mostly average. As a result, the litigants are left to suffer.

- Huge workload: Judges in high courts hear between 20 and 150 cases every day, or an average of 70 hearings daily. The average time that the judges have for each hearing could be as little as 2 minutes.

- Vulnerable population: They suffer as more than 10% of these pending cases are filed by women and about 5% by senior citizens. Poor litigants and undertrials stand to suffer the most due to judicial delay.

- Violation of Fundamental right: The backlog violates the spirit of Article 14 (right to equality before law) and Article 21 of the Constitution (right to life and liberty) that too by the protectors of the constitution.

- Economic Cost:

- It hampers dispute resolution, contract enforcement, discourage investment, stall projects, hamper tax collection, stress tax payers and escalate legal costs.

- Economic Survey said that although India jumped to 100th rank in the World Bank's Ease of Doing Business Report 2018, the country continues to lag on the indicator on enforcing contracts which marginally improved to 164 from 172 in the previous report.

- This leads to poor economic activity and hence lower per capita income.

- Social Impacts: A slow and tardy judiciary may lead to higher expenditure for people, higher poverty rates, poor public infrastructure and higher crime rates and more industrial riots.

Reforms Needed:

- The Economic survey 2017-18 suggested that the government could consider including efforts and progress made in alleviating pendency in the lower judiciary as a performance-based incentive for states.

- All India Judicial Service (AIJS) - In a recent speech commemorating 50 years of the Delhi High Court, Prime Minister Narendra Modi revisited the possibility of recruiting judges through an AIJS.

All India Judicial Service

Background:

- The Constitution drafting committees discussed Article 312, conferring power on the Parliament to create All India Services.

- Based on the Swaran Singh Committee’s recommendations in 1976, Article 312 was modified to include the judicial services, but it excluded anyone below the rank of district judge. Therefore, the trial courts are completely eliminated.

- The First Law Commission of India (LCI) came out with its comprehensive, and legendary, 14th Report on Reforms on the Judicial Administration, which recommended an AIJS in the interests of efficiency of the judiciary.

In Favour of All India Judicial Service:

- Direct recruitment of judges from the entry level onwards would be handled by an independent and impartial agency.

- The process of recruitment would be through open competition, and if designed with the right incentives of pay, promotion and career progression, it could potentially become an attractive employment avenue for bright and capable young law graduates.

- The persons eventually selected into the judiciary would be of proven competence. Simultaneously, the quality of adjudication and the dispensation of justice would undergo transformative changes across the judicial system, from the lowest to the highest levels.

- A career judicial service will make the judiciary more accountable, more professional, and also more equitable.

- The Supreme Court has itself said that an AIJS should be set up, and has directed the Union of India to take appropriate steps in this regard.

Against All India Judicial Service:

- First that lack of knowledge of regional languages would affect judicial efficiency;

- Second, that avenues for promotion would be curtailed for those who had already entered through the state services; and

- Third, that this would lead to an erosion of the control of the high courts over the subordinate judiciary, which would, in turn, affect the judiciary’s independence.

In a longer-term perspective, uniformity in selection processes and standards, as offered by an AIJS, has many advantages.

- Reducing the length of summer/winter vacations when the courts shut down en masse as has been put in petition in Supreme Court. The vacation benches, hearing urgent matters during the period does not suffice. In 230th Law Commission in its report “reform in Judiciary” in 2009 recommended that there must be full utilization of the court working hours and Grant of adjournment must be guided strictly by the provisions of Order 17 of the Civil Procedure Code.

- Courts must make use of innovative tools such as LokAdalats, Gram Nyayalays and Fast Track Courts for speedy justice disbursal.

- Endless possibilities of Information Technology should also be fully exploited to make procedures more transparent and less cumbersome.

- The situation demands a massive infusion of both manpower and resources.

Positive changes in Judiciary:

- World Bank lauds creation of National Judicial Data Grid in Ease of Doing Business report, the report states that the introduction of the Grid “made it possible to generate case management reports on local courts, thereby making it easier to enforce contracts”.

- Gram Nyayalaya – mobile village courts in India established under Gram Nyayalayas Act, 2008 for speedy and easy access to justice system in the rural areas of India.

Conclusion:

While improving judicial strength is a necessity—the 120th report of the Law Commission had talked of the need to bring this to 50 per million but making courts function for more number of days in a year than at present, and for more number of hours every day is also essential to clear the backlog.

Economic Survey 2017-18 called for coordinated action between government and judiciary to reduce pendency of commercial litigation for improving ease of doing business (EODB) and boost economic activities.

Learning Aid

Practice Question:

One of the underlying reasons behind the high pendency is the inordinate delay in filling up the vacancies of judicial officers. Critically analyse the statement in the light of the Supreme Court pulling up various state governments and High Courts for delay in filling vacancies in subordinate judicial services.