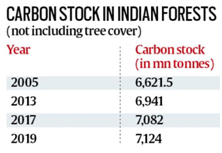

The State of Forest Report (SFR) 2019, while showing an increase in the carbon stock trapped in Indian forests in the last two years, also shows why it is going to be an uphill task for India in meeting one of its international obligations on climate change.

Issue

Context

The State of Forest Report (SFR) 2019, while showing an increase in the carbon stock trapped in Indian forests in the last two years, also shows why it is going to be an uphill task for India in meeting one of its international obligations on climate change.

Background

- India, as part of its contribution to the global fight against climate change, has committed itself to creating an “additional carbon sink of 2.5 to 3 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent” by 2030.

- That is one of the three targets India has set for itself in its climate action plan, called Nationally Determined Contributions, or NDCs, that every country has to submit under the 2015 Paris Agreement.

- The other two relate to an improvement in emissions intensity, and an increase in renewable energy deployment.

- India has said it would reduce its emissions intensity (emissions per unit of GDP) by 33% to 35% by 2030 compared to 2005.

- It has also promised to ensure that at least 40% of its cumulative electricity generation in 2030 would be done through renewable energy.

What is the relationship between forests and carbon?

- Forests, by absorbing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere for the process of photosynthesis, act as a natural sink of carbon.

- Together with oceans, forests absorb nearly half of global annual carbon dioxide emissions.

- In fact, the carbon currently stored in the forests exceeds all the carbon emitted in the atmosphere since the start of the industrial age.

- An increase in the forest area is thus one of the most effective ways of reducing the emissions that accumulate in the atmosphere every year.

How do the latest forest data translate into carbon equivalent?

- The latest forest survey shows that the carbon stock in India’s forests (not including tree cover outside of forest areas) have increased from 7.08 billion tonnes in 2017, when the last such exercise had been done, to 7.124 billion tonnes now.

- This translates into 26.14 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent as of now.

- It is estimated that India’s tree cover outside of forests would contribute another couple of billion of tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent.

How challenging does this make it for India in meeting its target?

- An assessment by the Forest Survey of India (FSI) last year had projected that, by 2030, the carbon stock in forests as well as tree cover was likely to reach 31.87 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent in the business as usual scenario.

- An additional 2.5 to 3 billion tonnes of sink, as India has promised to do, would mean taking the size of the sink close to 35 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent.

- Considering the rate of growth of the carbon sink in the last few years, that is quite a stiff target India has set for itself.

- In the last two years, the carbon sink has grown by just about 0.6%%. Even compared to 2005, the size of carbon sink has increased by barely 7.5%.

- To meet its NDC target, even with most optimistic estimates of carbon stock trapped in trees outside of forest areas, the sink has to grow by at least 15% to 20% over the next ten-year period.

Forest cover up but large tracts of dense forest have turned non-forest

- The biennial State of Forest Report (SFR) announced an overall gain of 3,976 sq km of forests in India since 2017.

- There is a loss of 2,145 sq km of dense forests that have become non-forests in those two years.

- Dense forests are defined by canopy cover: over 70% is considered very dense and 40-70% medium dense.

- Unlike natural forests, commercial plantations grow rapidly and show up as dense cover in satellite images.

- A monoculture, however, cannot substitute natural forests in biodiversity or ecological services

- Some of these are fast-growing species such as bamboo in the north-eastern region. Also rubber and coconut plantations in the southern states.

- Since 2003 when this data was first made available, 18,065 sq km — more than one third of Punjab’s landmass — of dense forests has become non-forests in the country.

- Forestland roughly the combined area of Tamil Nadu and West Bengal holds no forests at all. There is no denial that the gain in forest cover is outside forestland.

What is the way forward?

- There are two key decisions to be made in this regard — selection of the baseline year and addition of the contribution of the agriculture sector to carbon sink.

- The baseline year can impact the business-as-usual projections for 2030. BAU projections are obtained using policies that existed in the baseline year. Now, there has been a far greater effort in recent years to increase the country’s forest cover.

- So a 2015 baseline would lead to a higher BAU estimate for 2030 compared to a 2005 baseline when less effort were being made to add or regenerate forests.

- If 2005 baseline is used, India’s targets can be achieved relatively easily.

- India’s emissions intensity target uses a 2005 baseline, so there is an argument that the forest target should also have the same baseline.

- When India announced its NDC in 2015, it did not mention the baseline year. It has to decide on it before it reconfirms its NDC targets ahead of the next climate change meeting in Glasgow.