Introduction

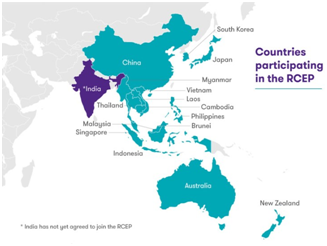

A day after the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (RCEP) was signed by 15 countries — without India — External Affairs Minister S Jaishankar said that the impact of past pacts has been de-industrialization and the consequences of future ones would lock India into “global commitments” — many of them not to India’s advantage. He also said that those who argue “stressing openness and efficiency” do not present the full picture and that this was “equally a world of non-tariff barriers of subsidies and state capitalism”. Fifteen Asia-Pacific nations, including China, signed the world's biggest trade agreement, the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), sans India with hopes that it will help recover from the shocks of the COVID-19 pandemic. The RCEP was signed after eight years of negotiations at the conclusion of the annual summit of Southeast Asian leaders and their regional partners, held virtually this year due to the COVID-19 pandemic. India, one of the leading consumer-driven market in the region, pulled out of talks last year, concerned that the elimination of tariffs would open its markets to a flood of imports that could harm local producers. But other nations have said in the past that the door remains open for India's participation in the RCEP, influenced by China. In this edition of the Big Picture, we will analyze India’s stand on RCEP.

Edited Excerpts from the debate

What is RCEP and why is it important?

- The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership was introduced during the 19th Asean meet held in November 2011.

- The RCEP negotiations were kick-started during the 21st ASEAN Summit in Cambodia in November 2012.

- It took eight years and 31 rounds of negotiation before the 15 nations reached an agreement on RCEP.

- Member states of ASEAN and their FTA partners are Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, Vietnam, China, Japan, South Korea, Australia, and New Zealand.

- It aims to lower tariffs, open up trade in services, and promote investment to help emerging economies catch up with the rest of the world.

How ‘big’ is RCEP?

- It’s one of the largest trade pacts ever signed, with its member nations representing just under a third of the world’s population and economic output.

- The 15 countries together account for a third of the world gross domestic product (GDP) and almost half the world’s population, with the combined GDPs of China and India alone making up more than half of that.

- RCEP's share of the world economy could account for half of the estimated $0.5 quadrillion global (GDP, PPP) by 2050.

Why India opted to quit the deal?

- On November 4, 2019, India decided against joining the 16-nation Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) trade deal, saying it was not shying away from opening up to global competition across sectors, but it had made a strong case for an outcome which would be favorable to all countries and all sectors.

- The decision to come out of the RCEP was predominantly “the unsatisfactory address of India’s outstanding issues and concerns”.

- During negotiations, though several issues were ironed out towards

- preparing the mutual ground for trade and market access

- the concern around protecting the interests of India’s domestic producers couldn’t be sidelined with the growing demand from several quarters to keep them on the exclusion list of RCEP (viz. the dairy, textile sectors, pharmaceuticals, steel & chemical industries, etc).

- It raised alarm about market access issues, fearing its domestic producers could be hard hit if the country was flooded with cheap Chinese goods.

- Textiles, dairy, and agriculture were flagged as three vulnerable industries.

RCEP, without India

- Without India, the RCEP trade bloc still stands as the world’s largest free-trade bloc with a combined GDP of over 26 trillion and nearly one-third of the world’s population.

- For India, the issue of tariff elimination remained critical all through the negotiation, as the post-RCEP scenario would widen the existing trade deficit and severely harm some vulnerable sectors.

- Though the post-RCEP scenario might offer India an opportunity for greater market access, imports from partner countries would increase at a much higher rate than export in a reduced tariff situation.

- Even with an optimistic assumption of low tariff cuts in sensitive sectors such as agriculture, dairy products, and other MSMEs sectors, it could still increase India’s imports more than exports.

What is China's role in RCEP?

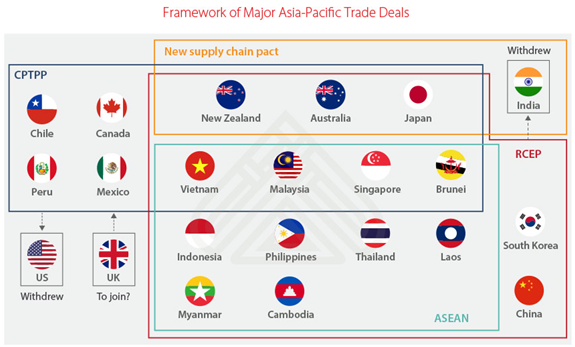

- RCEP was pushed by Beijing in 2012 to counter another FTA that was in the works at the time: The Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). The US-led TPP excluded China.

- However, in 2016 US President Donald Trump withdrew his country from the TPP.

- Since then, the RCEP has become a major tool for China to counter the US efforts to prevent trade with Beijing.

What does it mean for the US? -

- A new US administration under President-elect Joe Biden will likely focus more on Southeast Asia, analysts say, although it remains unclear whether he would want to rejoin the CPTPP.

- To understand what the RCEP means for the United States, it’s important to look at the big trade deal that got away: the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP).

- The TPP was part of the Obama Administration’s “pivot” to Asia, and was intended to counter China’s rise by improving economic cooperation with regional allies.

- The TPP included a raft of environmental, human rights, intellectual property, and labor regulations that stood to bolster U.S. competitiveness.

- The authors of the deal hoped that if enough of China’s other major trade partners signed on, China would be forced to join as well—and comply with the new standards.

- But Trump made quitting the TPP a campaign issue in 2016, painting it as another free trade deal that would ship U.S. manufacturing jobs overseas.

- The agreement morphed into the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), which 11 nations—including Japan, Canada, and Australia—have signed.

- But, without the heft of the U.S. in the mix, China has not signed on.

- The RCEP, unlike the TPP, does not include detailed provisions related to environmental and labor standards.

Conclusion

While the conclusion of RCEP’s negotiations is a substantial achievement on several fronts, ASEAN cannot be apathetic to wider trends and rest on its laurels. All too often, ASEAN has been the “businessman who oversells and under-delivers.” ASEAN members must muster the political will to ensure implementation and proper follow-through while continuing to work toward bringing India back into the agreement. Despite criticism surrounding the ASEAN Way and its flexible and consensus decision-making processes, it is precisely these qualities that have made ASEAN and RCEP resilient and poised to succeed.

More Articles