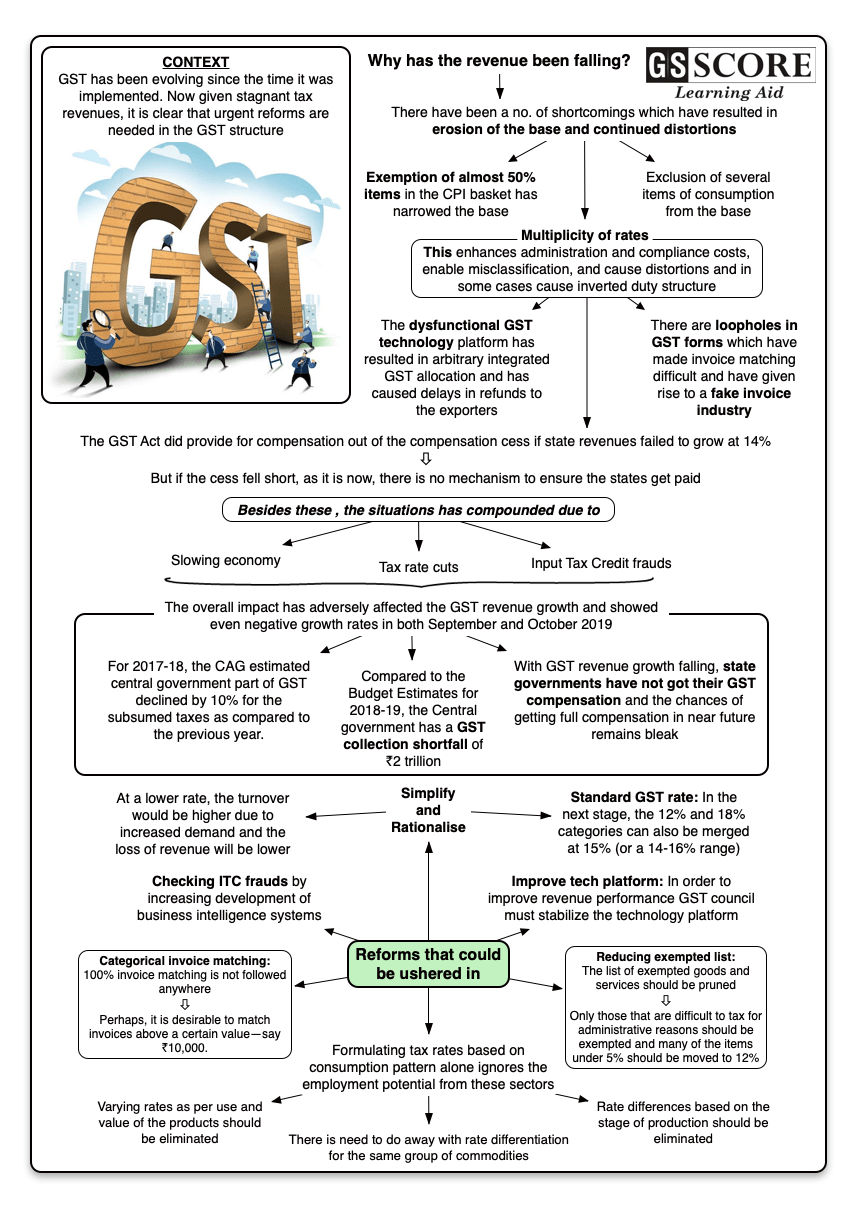

The Goods and Services Tax (GST) has been evolving since the time it was implemented. Now given stagnant tax revenues, it is clear that urgent reforms are needed in the GST structure.

Issue

The Goods and Services Tax (GST) has been evolving since the time it was implemented. Now given stagnant tax revenues, it is clear that urgent reforms are needed in the GST structure. It is a good time to analyse the revenue implications and economic impact of GST, as well as identify the reform areas to increase revenue productivity and minimize administrative, compliance and distortion costs.

Background:

- The overall GST collections have been below estimates and showed even negative growth rates in both September and October 2019.

- Compared to the Budget Estimates for 2018-19, the Central government has a GST collection shortfall of ?2 trillion.

- Slowing economy, tax rate cuts and Input Tax Credit (ITC) frauds have impacted the GST revenue growth. A total of 9,385 cases of tax fraud through ITC, amounting to ?45,682 crore, were detected until October 2019. The undetected amount would be much larger.

- With GST revenue growth falling, state governments have not got their GST compensation and the chances of getting full compensation in near future remains bleak.

- The recently announced corporate tax cuts will also reduce the tax transfers by the Centre to states.

Analysis

Why GST?

- The starting point of India’s nationwide goods and services tax (GST) was the Vijay Kelkar task force on tax reforms.

- The need for a uniform, predictable and stable indirect tax regime across the country was axiomatic to a frictionless common economic market.

- Being a consumption tax GST is easier to collect than an income tax, since it is collected on every tiny transaction and leaves an electronic trail that makes evasion difficult. This makes it administratively attractive.

- Structural Benefits: The GST constitutes a major tax reform since it eliminates the earlier system’s tax-upon-tax cascade, encourages inter-state commerce, provides an inbuilt incentive for compliance, reduces leakages, corrects the earlier skew which favoured imported goods, and is fully electronic.

The Gains

- Abolition of interstate check-posts has reduced the impediments to the interstate movement of goods and helped create a national common market.

- It is estimated that the long-distance travel time for goods transportation has reduced by almost 20%.

- The reform has also improved supply- chain management.

- The abolition of interstate sales tax has made the tax destination-based and reduced inequitable interstate tax exportation.

- Compliance mechanisms have improved due to linkage and exchange of information between income-tax and GST departments.

- Cascading (tax on tax) has reduced due to more a comprehensive mechanism to credit input taxes against the taxes on outputs.

- Earlier, the central excise duty was levied at the manufacturing stage and it cascaded into the final retail value.

- The state value-added tax was earlier levied on the already paid value of excise duty.

- The inclusion of taxes like central sales tax, octroi, purchase taxes and luxury taxes on hotels in GST too have substantially reduced cascading effects.

- Creation of GST Council is an important innovation in cooperative federalism. It has helped minimize the transaction cost of formulating domestic consumption taxes of the Centre and states.

Challenges

- The most important constraint in current GST structure is stagnant revenues:

- For 2017-18, the CAG estimated central government part of GST declined by 10% for the subsumed taxes as compared to the previous year.

- GST implemented in India has a number of shortcomings which have resulted in erosion of the base and continued distortions:

- Large list of exemptions

- Multiplicity of rates

- Exclusion of several items of consumption from the base.

- Exemption of almost 50% items in the CPI basket has narrowed the base.

- The tax is levied at four different rates (at 5%, 12%, 18% and 28%) in addition to the special rates on precious metals (0.25%), gold (3%) and job work in diamond industry (1.5%).

- Multiplicity of tax rates enhance administration and compliance costs, enable misclassification, and cause distortions and in some cases cause inverted duty structure.

- Rates have been varied set according to use of the product and value of the product.

- Items considered as inputs are taxed lower as compared to those judged as outputs.

|

Inverted duty structure is a situation where import duty on finished goods is low compared to the import duty on raw materials that are used in the production of such finished goods. This causes the manufactured goods by the domestic industry to become uncompetitive against imported finished goods. |

- A special cess is also levied at varying rates on items under 28% categories and, in the case of some class of automobiles there’s a cess of 22%, resulting in the total incidence of 50%.

- High tax rates on automobiles, building and construction material at a time when demand conditions are already weak has caused further slowdown in these sectors.

- By excluding petroleum products, real estate and electricity, 40% of the internal indirect taxes at the Centre as well as states are not in the net.

- There are loopholes in GST forms which have made invoice matching difficult and have given rise to a fake invoice industry.

- The dysfunctional GST technology platform has resulted in arbitrary integrated GST allocation and has caused delays in refunds to the exporters.

- The GST Act did provide for compensation out of the compensation cess if state revenues failed to grow at 14%. But if the cess fell short, as it is now, there is no mechanism to ensure the states get paid.

- Given that GST comprises nearly 60% of tax revenues of states, falling revenues and default in GST compensation is bringing activities of the States to halt.

- While the Centre has more fiscal manoeuvring space, the decline in tax revenue growth is impacting state capex more directly.

- States are facing pressure on fiscals, some already resorting to ways and means and even overdrafts.

- State governments have curbed their capital expenditure, a move which will further delay the revival of private investment cycle.

- Given that roughly two-thirds of the general government capex is contributed by states, the slashing of capex by states can deepen economic slowdown.

Reforms needed

- Simplify and Rationalise: The full potential of GST reform depends upon further simplification and rationalization.

- Improve tech platform: In order to improve revenue performance GST council must stabilize the technology platform.

- Higher threshold: The threshold for registration should be kept at a reasonably high level.

- The data from Karnataka for 2017-18 shows that 93% of taxpayers had less than ?50 lakh turnover and they accounted for 6.5% of the turnover and 12% of the tax paid.

- Hence it is important to focus on those with high turnovers, who could contribute to a higher tax percentage.

- Having a reasonably high threshold helps also the cause of equity.

- Categorical invoice matching: 100% invoice matching is not followed anywhere. Empirical results from Koreas suggest that it tried 100% invoice matching but gave it up. Perhaps, it is desirable to match invoices above a certain value—say ?10,000.

- Reduce multiplicity of rates: Reducing the number of tax rates should begin by getting rid of the 28% category altogether and transferring them to the 18% slab.

- At a lower rate, the turnover would be higher due to increased demand and the loss of revenue will be lower.

- Reducing exempted list: The list of exempted goods and services should be pruned. Only those that are difficult to tax for administrative reasons should be exempted and many of the items under 5% should be moved to 12%.

- There is need to include the petroleum products and electricity in the GST base.

- Petroleum products contribute about 42% of the revenue from domestic indirect taxes and including it will ensure competitiveness.

- Standard GST rate: In the next stage, the 12% and 18% categories can also be merged at 15% (or a 14-16% range). This will simplify the tax system.

- Broadening the basis of tax formation: Formulating tax rates based on consumption pattern alone ignores the employment potential from these sectors.

- Varying rates as per use and value of the products should be eliminated.

- Rate differences based on the stage of production should be eliminated.

- There is need to do away with rate differentiation for the same group of commodities.

- Separate excise for demerit goods: “Demerit goods" such as tobacco and its products are taxed in the 28% category. Cigarettes are taxed differently according to their lengths. It is important to levy high tax rates on such items for sumptuary reason, but the proper method is to levy GST at the standard rate and have a separate excise on them.

- Phased reforms: All reforms should be sequenced and calibrated over a period of two-three years, so that there are no shocks in the economic system.

- Expert consultation: There is need of a strong technical secretariat comprising of administrators, economists, accountants and lawyers to advise the GST Council and present options so that informed decisions are taken.

- Equally important is the need to make all data, which is not sensitive to enforcement, available in public domain.

- Reluctance to share the data is a major constraint for undertaking independent research. Even CAG has raised this issue.

- States’ involvement: Onus of fixing GST should not just be central government’s job; states should also focus on the ground issues instead of only focusing on getting compensation.

- Checking ITC frauds: In order to avert input tax credit (ITC) frauds there is need for increasing development of business intelligence systems to detect such frauds, and setting up dedicated units in each state.

|

The saga of what the GST rate should be?

|

Conclusion

The implementation of GST in a large and diverse federal country ruled by different political parties is a remarkable achievement. Currently, the most important constraint in GST is stagnant revenues and unless immediate measures are taken to raise revenue productivity, the euphoria of GST will wane. Significant reforms are needed to ensure better compliance and to minimize economic distortions.

Learning Aid