9th November 2023 (14 Topics)

Context:

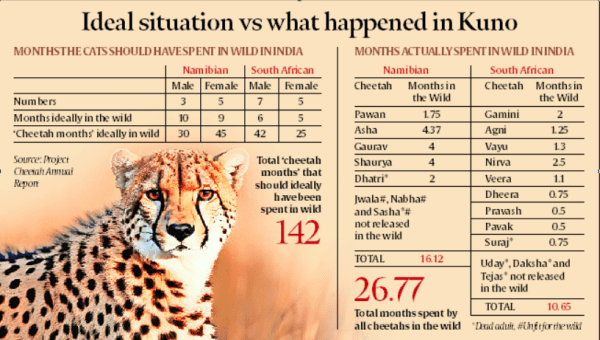

12 months since Cheetah arrived in India in September 2022, each of the three Namibian male Cheetah have spent 10 months in the wild, and each of the five Namibian females have spent nine months in the wild.

Cheetah Reintroduction Report of One Year:

- Intent of Cheetah Project: A year after it was launched, Project Cheetah, India’s ambitious attempt to introduce African cats in the wild in the country, has claimed to have achieved short-term success on four counts: 50% survival of introduced cheetahs, establishment of home ranges, birth of cubs in Kuno, and revenue generation for local communities.

The Assessment of Claims:

- Survival Claims: The test of survival is in the wild, not in captivity where animals are under protective care. According to India’s official Cheetah Action Plan, the male and female cats from both Namibia and South Africa were to spend two and three months respectively inside bomas (enclosures) before being released in the wild.

- Cheetah in Wild: In the 12 months since they arrived in India in September 2022, each of the three Namibian males have spent 10 months in the wild, and each of the five Namibian females have spent nine months in the wild.

- In all then, the eight cheetah imports from Namibia have spent a cumulative 75 ‘cheetah months’ in the wild.

- In all then, the eight cheetah imports from Namibia have spent a cumulative 75 ‘cheetah months’ in the wild.

Reality of the Project Cheetah:

- Cheetah spent about 16 ‘cheetah months’ outside the bomas.

- Together, the 12 South African imports should have spent a cumulative 67 ‘cheetah months’ in the wild. In reality they spent not even 11 ‘cheetah months’ in the wild.

- The project lost 40% of its functional adult population. Of the 20 cats that arrived in India, six died, and two were unfit for the wild. Four cubs were born in India, three of which died, and the fourth is being raised in captivity.

Compromises and Mistakes done:

- Non-release of Cheetah: Three of the eight Namibian cheetahs, who were never released outside the bomas in Kuno — were captive-raised, reportedly as “research subjects”. They were offered to India to meet the “hard deadline” for the import.

- India’s out breach of commitments for Cheetah introduction: To get the cheetahs, India promised to support Namibia for “sustainable utilisation and management of biodiversity at international forums”. Weeks after the cheetahs arrived, India abandoned its decades-old stand by abstaining at the CITES vote against trade in elephant ivory.

- Gene variations within Cheetah: In Kuno, captive breeding was attempted by putting the sexes together in hunting bomas. However, due to extremely low genetic variation within the species, a cheetah female is very selective in seeking out most distantly related males. That is why giving males access to a female not in heat can lead to violence.

Kuno’s carrying capacity:

- Project Cheetah’s Goal: The project’s original goal, “to establish a free-ranging breeding population of cheetahs in and around Kuno”, has been diluted to “managing” a meta population through assisted dispersal.

- Cheetah Action Plan: The Cheetah Action Plan estimated “high probability of long-term cheetah persistence” within populations that exceed 50 individuals. Cheetal is the cheetah’s prime prey in Kuno where project scientists reported per-sq-km cheetal density of 5 (2006), 36 (2011), 52 (2012) and 69 (2013).

- Carrying Capacity of Kuno: The feasibility report in 2010 estimated that 347 sq km of Kuno sanctuary could sustain 27 cheetahs, and the 3,000 sq km larger Kuno landscape could hold 70-100 animals.

Way Forward: Paradigm shift ahead

- Limitations of Kuno: Since Kuno cannot support a genetically self-sustaining population, the project’s only option is a meta-population scattered over central and western India. But unlike leopards, which dominate this landscape, cheetahs cannot travel the distances between these pocket populations on their own.

- South African Model: A solution would be to borrow from the South African model that periodically translocates animals from one fenced reserve to another to maintain genetic viability. But if this “assisted dispersal” becomes the new normal, the case for maintaining forest connectivity that allows natural dispersal of wildlife will be severely weakened.