Nobel Prize in chemistry 2019 awarded for work on lithium-ion batteries

Context

Nobel Prize in chemistry 2019 awarded for work on lithium-ion batteries

About

- The first rechargeable battery came about in 1859. These were made from lead-acid, and are still used to start gasoline- and diesel-powered vehicles today.

- Stanley Whittingham discovered an extremely energy-rich material, which he used to create an innovative cathode in a lithium battery. This battery was made from titanium disulphide.

- The battery’s anode was partially made from metallic lithium, which has a strong drive to release electrons. It resulted in a battery that had great potential, just over two volts.

- The big advantage of this technology was that lithium-ion stored about 10 times as much energy as lead-acid or 5 times as much as nickel-cadmium

- Lithium-ion batteries were also extremely lightweight and required little maintenance.

- Lithium ion batteries using cobalt oxide can boost the lithium battery's potential to four volts.

Benefits and uses:

- The advantage of lithium-ion batteries is that they are not based upon chemical reactions that break down the electrodes, but upon lithium ions flowing back and forth between the anode and cathode.

- They are lightweight, rechargeable, powerful batteries, now used in everything from mobile phones to laptops and long-range electric vehicles.

- Battery technology helps replace carbon-emitting sources because it allows power companies to store excess solar and wind power when the sun does not shine nor the wind blow, making possible a fossil fuel-free society and combating the effects of climate change.

- They are also capable of being miniaturized and used in devices like implanted pacemakers.

- They can be scaled up to power a car or a home.

Mechanics of Lithium ion battery:

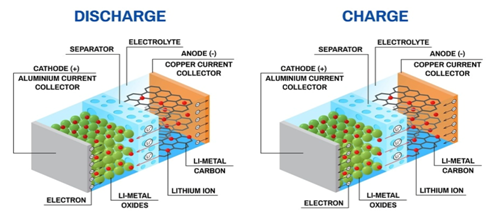

- Lithium-ion batteries are powered by flows of lithium ions crossing from one material to another.

- When the battery is in use, positively-charged lithium ions pass from an anode to a cathode, releasing a stream of electrons along the way that form an electric current.

- When the battery is being recharged, lithium ions flow in the opposite direction, resetting the battery to do it all over again.

Issues and concerns: - The demand for lithium is spiking and will continue to increase as more battery-powered cars and storage units hit the market.

- Lithium mining requires millions of gallons of water and in places like Tibet and dry regions of South America, selling water became a dirty business.

- Poorly run mines can also contaminate local water supplies.

- Cobalt is also in short supply, and mining of that metal in places like the Congo Basin is driving environmental destruction, child labour, and pollution.

- More than half of lithium is gathered using brine extraction from deep inside the earth, and the rest is still mined traditionally from rock.

- Both methods have caused environmental damage to areas around lithium processing operations.

- And as the demand for lithium increases, companies may resort to using energy-intensive heating to speed up brine evaporation.

- Once lithium-ion batteries are used up in electronics, they are often disposed of improperly by consumers. Only a small percentage is collected and recycled. Most end up in landfills.

- Recycling the batteries and removing these increasingly precious metals is also costly and sometimes dangerous.

- There are a limited number of times that a lithium-ion battery can be replenished before it deteriorates and can no longer hold a charge.

- In addition, a faultily designed lithium-ion battery can turn into a miniature bomb.

- Technologists often point to lithium-ion as an innovation roadblock: there’s not much that engineers can do beyond making the batteries bigger and implementing software algorithms to make hardware more power efficient.