- Although India’s healthcare sector has grown rapidly over the last five years (Compound Annual Growth Rate of 22%), COVID-19 has brought to the forefront persistent challenges such as a weak health system, lack of quality infrastructure, and lack of quality service delivery to vulnerable populations.

- India's healthcare spending is 6% of GDP, including out-of-pocket and public expenditure.

- The combined total government expenditure of both central and state is 1.29% of GDP.

- India spends the least among BRICS countries: Brazil spends the most (9.2%), followed by South Africa (8.1%), Russia (5.3%), China (5%).

- The National Health Policy has mandated states to increase health spending on primary care by at least 10% every year to reach the target of spending 2.5% GDP.

- In addition, the government has liberalized FDI norms to allow up to 100% investment in almost all sectors (hospital construction, medical devices, insurance, and in greenfield projects related to healthcare, biotechnology, pharmaceutical) except for brownfield sectors like healthcare, biotechnology, and pharmaceutical where it is up to 74%.

- Despite this, 66% of the FDI inflows in the past two decades were in drugs and medicines, followed by hospitals & diagnostic centers and medical & surgical appliances.

- Before COVID-19, it was estimated that over $500 billion of private capital must be mobilized annually to meet all of India's sustainable development goals by 2030.

- To address access, affordability, and quality healthcare, it is estimated that under a business-as-usual scenario USD 256 billion would be needed by 2034 to achieve sustainable development goals related to health.

- But with the adoption of new technologies and a focus on prevention and wellness, the funding requirement is estimated at USD 156 billion.

- This implies that government and philanthropic funding will need to be applied even more judiciously.

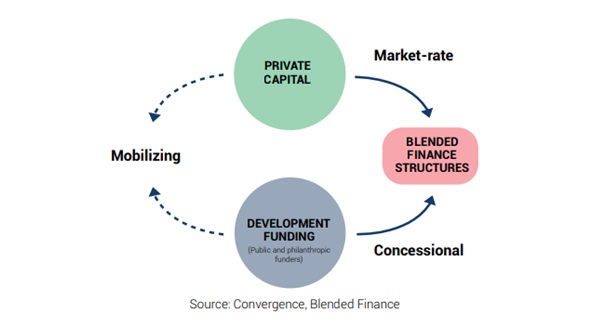

- The potential solution is blended finance, i.e., using a combination of public or philanthropic (grant) and commercial (equity or debt) capital to create new funding structures towards achieving developmental impact in healthcare.

- Blended finance is an approach towards financing where catalytic funding (e.g., grants and concessional capital) from public and philanthropic sources is utilized to mobilize additional private sector investment to realize social goals and outcomes.

- Blended finance is the strategic use of concessional capital and private capital in projects where the perceived risks are too high for private players to participate alone.

- By combining concessional and commercial capital, blended finance can achieve acceptable risk/return profiles for different types of financing partners, including private capital

- Blended finance is a structuring approach that allows enterprises to invest alongside each other while achieving their different objectives: financial return, environmental/social impact, or a blend of both.

- Blended finance is therefore not a single instrument but rather a financial structure in which different investors with different investment priorities can participate.

- Blended finance is expected to achieve additionality, both financial and developmental.

- The definition requires that blended finance mobilizes additional finance (financial additionality) which is used for sustainable development (development additionality).

- In other words, blended finance is a financial mechanism to deliver additional development impact by mobilizing commercial capital that would otherwise not be available if left to market forces

Blended Finance can be characterized by three main features:

- LEVERAGE-Use of development finance and philanthropic funds to attract private capital into deals

- IMPACT-Investments that drive social, environmental and economic progress

- RETURNS-Financial returns for private investors in line with market expectations, based on real and perceived risks

- Reduces dependency on government debt and sovereign guarantees

- Builds a pipeline of commercially viable social impact projects

- Reduces the risk premium through co-financing and co-investment Investments that drive social, environmental and economic progress

- Blended finance is a valuable tool for Bilateral and Multilateral agencies, Philanthropic Organizations, and Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) foundations to complement traditional grant-making and invest their monies in the form of loan/equity/guarantee in projects that deliver financial and social returns.

- It has enabled large foundations such as the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, Rockefeller Foundation, Michael and Susan Dell Foundation, Open Society, Children’s Investment Fund Foundation, bilateral and multilateral agencies like USAID, UKAID and others to bridge the risk appetite gap and subsidize financial risk through grants or forms of low-cost returnable capital to direct commercial capital into development initiatives.

- Blended finance also has a crowding-in effect wherein, when new models are workable and successful, other commercial players also start providing funding in the space independently using similar models.

- Over a period, this leads to an increase in the total capital deployed in the target areas.

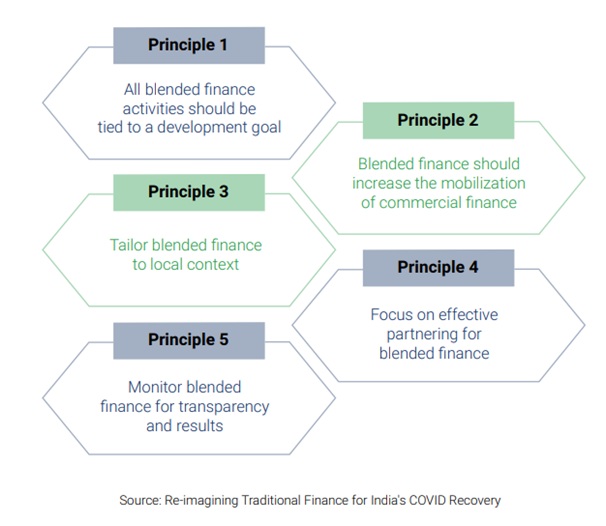

- The blended finance principles outline the practical steps and elements that can facilitate the design and implementation of blended finance programs.

- These principles aim to enhance the growth and expand the quality of finance that can be mobilized and invested in the sustainable development of economies globally.

- With the changing landscape of developmental and sustainable financing, numerous innovative instruments are deployed across the nations, developing new approaches and practices.

- The five underlying principles below reflect the new developments and best practice examples for blended finance and act as a guiding framework to successfully mobilize private capital to maximize the impact for sustainable development.

Some key challenges hampering the adoption of blended finance at scale include:

- Lack of a private sector mobilization strategy and action plan: Blended finance is one tool in the development toolbox centered on increasing the quantum of financing to SDG projects. Donors are the main source of the catalytic funding that create the market-equivalent investments that mobilize private investment, but they have not prioritized and budgeted private sector mobilization as a necessity to significantly narrow the SDG financing gap. Further, the idea of providing financial returns to risk investors has not been adopted widely by the development sector community.

- Low levels of coordinated participation from the government: Representation from governments is crucial to scaling blended finance. The current government system is based on input-based budgeting, while blended finance structures such as SIBs require a shift to outcome-based funding. The tendering process involved in creating structures such as SIBs creates delays in structuring blended finance transactions.

- High transaction costs and long timelines in structuring blended finance solution: Though the design and evaluation costs for structures such as DIBs and SIBs are decreasing over the years, these are still high. A blended finance solution's design and contracting time is typically higher than traditional grants or pure commercial investment. However, with structures like portfolio level guarantees or social success notes, the time to execute transactions is coming down due to the portfolio-level approach, which provides both higher impact and scale. The blended finance intermediaries executing these structures in short timelines and with lower transaction costs should act as a harbinger of blended finance and collaborate and strategize with other structuring agencies to minimize the lead time to increase the adoption of blended finance.

- Lack of transparency on blended finance activity limits its scalability: Concessional capital providers do not publicly disclose financial terms or ex-post development outcomes, limiting the evidence base for blended finance as a development tool, while private investors do not disclose data on financial performance due to confidentiality concerns. Together, this hinders blended finance from scaling.

- Regulatory Constraints in mobilizing grant capital such as CSR funds: The government of India mandated in 2013 that 2% of corporate profits be directed to the development sector, boosting the spending pool for CSR activities by an estimated $7 billion. While the initiative started slowly, some CSR initiatives, impact investors, and donors are now actively exploring creative channels to best combine the CSR mandate with the financial innovation in the market. However, legal obstacles and regulatory constraints still exist for the use of CSR in blended finance structures, and it requires clear guidance from regulators to make the best use of CSR funds.

- The ecosystem for blended finance is underdeveloped: There is a lack of financial intermediation in the blended finance market and addressing the SDG investment gap more generally. Donors and investors are looking to channel large amounts of capital towards market opportunities aligned with the SDGs. Yet the projects are often small, and few intermediaries in the market are equipped to manage these financial flows. Even when blended finance can successfully aggregate cross-border investment pools, few intermediaries can channel these flows effectively.

- Focused mandate restricts flexibility: Each party involved in a blended finance transaction has its focused mandate restricting the flexibility of finance required for blended financing structures. For instance, philanthropic institutions are guided by developmental impact in line with their specific mandates determining outcomes, geographies, target beneficiaries, thematic areas. In contrast, commercial institutions engage in blended finance with commercial motives, seeking a commercial return according to their regulatory requirements.

- Lack of openness from NGOs & CSO for availing commercial capital: Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs)/Civil Society Organizations (CSOs) that have higher penetration to the most vulnerable sections of the society and thereby can help achieve larger impact, are not open to commercial investments. These organizations mostly focus on raising grants to provide services to end beneficiaries without charging them. This restricts their ability to get on to a common term with the commercial institutions, which require sustainable models. Further, focusing on the specific needs of vulnerable populations necessitates more localized support, which limits the scale of these NGOs/CSOs.

Related Articles