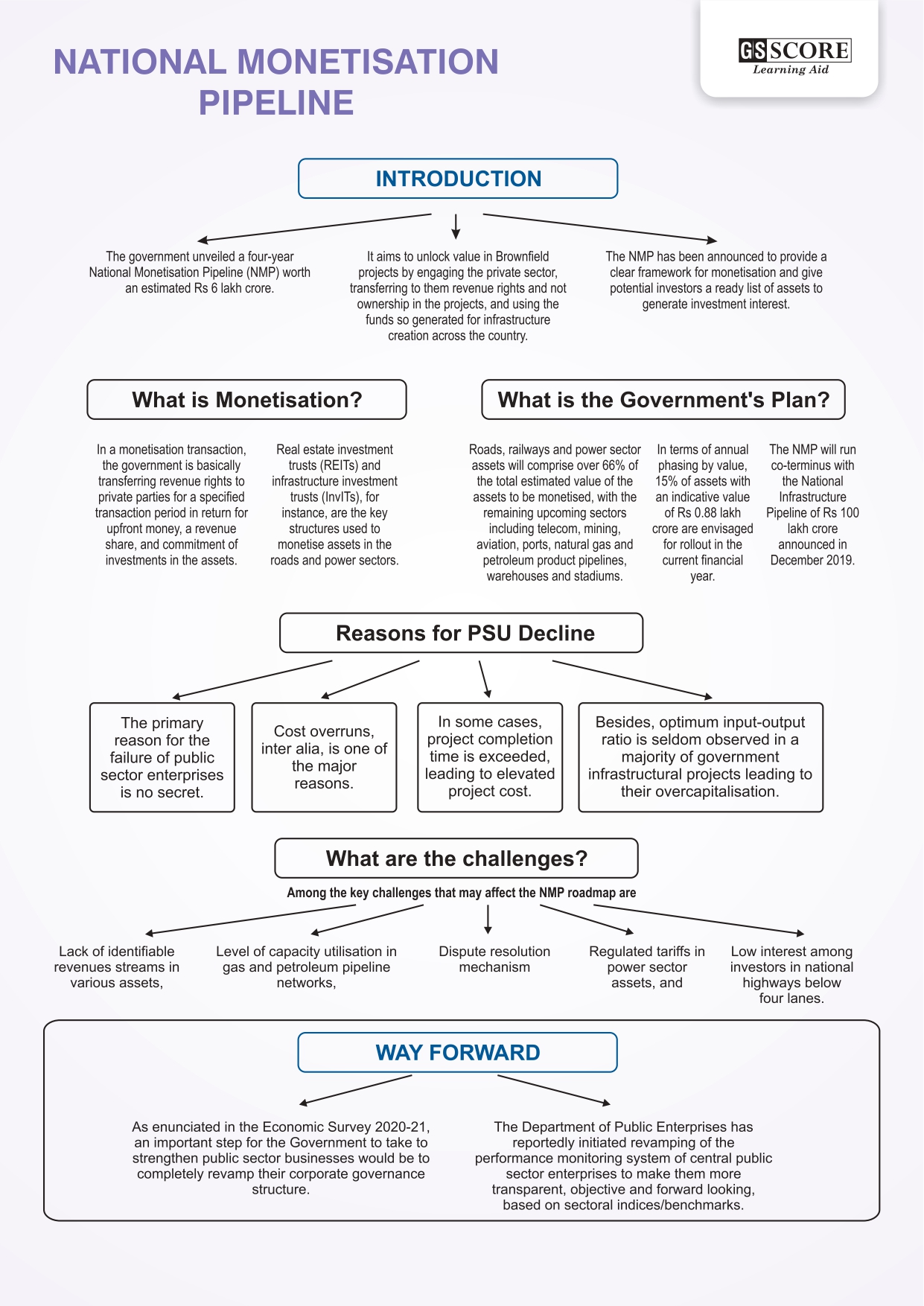

- The primary reason for the failure of public sector enterprises is no secret.

- Cost overruns, inter alia, is one of the major reasons.

- In some cases, project completion time is exceeded, leading to elevated project cost so much so that either the project itself becomes unviable at the time of its launching or delays its break-even point.

- Besides, optimum input-output ratio is seldom observed in a majority of government infrastructural projects leading to their overcapitalisation.

- A reluctance to implement labour reforms, a lack of inter-ministerial/departmental coordination, poor decision-making, ineffective governance and excessive government control are other reasons for the failure of public infrastructural assets.

- Recently, the “Pradhan Mantri Gati Shakti National Master Plan” for multi-modal connectivity was launched by the Prime Minister with an aim ‘to synchronise the operations of different departments of 16 Ministries including railways and roadways for seamless planning and coordinated execution of infrastructure projects in a timely manner’.

- It is essentially a digital platform for information sharing among different Ministries and departments at the Union and State levels.

- It also entails analytical decision-making tools to disseminate project-related information and prioritise key infrastructure projects.

- Besides, it fosters a periodical review and monitoring of the progress of cross-sectorial infrastructure projects through the GIS platform in order to intervene if there is a need.

- In a monetisation transaction, the government is basically transferring revenue rights to private parties for a specified transaction period in return for upfront money, a revenue share, and commitment of investments in the assets.

- Real estate investment trusts (REITs) and infrastructure investment trusts (InvITs), for instance, are the key structures used to monetise assets in the roads and power sectors.

- These are also listed on stock exchanges, providing investors liquidity through secondary markets as well.

- While these are a structured financing vehicle, other monetisation models on PPP (Public Private Partnership) basis include: Operate Maintain Transfer (OMT), Toll Operate Transfer (TOT), and Operations, Maintenance & Development (OMD).

- OMT and TOT have been used in highways sector while OMD is being deployed in case of airports.

- Roads, railways and power sector assets will comprise over 66% of the total estimated value of the assets to be monetised, with the remaining upcoming sectors including telecom, mining, aviation, ports, natural gas and petroleum product pipelines, warehouses and stadiums.

- In terms of annual phasing by value, 15% of assets with an indicative value of Rs 0.88 lakh crore are envisaged for rollout in the current financial year.

- The NMP will run co-terminus with the National Infrastructure Pipeline of Rs 100 lakh crore announced in December 2019.

- The estimated amount to be raised through monetisation is around 14% of the proposed outlay for the Centre of Rs 43 lakh crore under NIP.

- The NMP is also very different from the United Progressive Alliance (UPA)-I’s ill-fated public-private partnership (PPP) infrastructure development of the mid-2000s.

- That programme was about attracting private parties to build, operate and then transfer ‘greenfield’ or new infrastructure projects under build-operate-transfer (BOT) concession agreements.

- These enjoined the winning private bidder to take not only the operating risk, but also the development and construction risk of the project, such as a toll road, from scratch.

- This was a complex and messy process. It involved the acquisition of land. This process became controversial and was subject to delay.

- It involved securing environmental and other regulatory approvals.

- These proved challenging to obtain. It involved meeting construction and design standards. Compliance with these became a source of friction between the concessioning authority and the concessionaire.

- All this undermined trust between the public and private parties and led to a huge volume of disputes for which there was no readily available resolution mechanism.

- In contrast, the NMP is about leasing out ‘brownfield’ infrastructure assets (such as an already operating inter-State toll highway) under a toll-operate-transfer (TOT) concession agreement.

- In such an arrangement no acquisition of land is involved. Nor does the concessionaire need to take any of the construction risk.

- The process promises to be much simpler and cleaner than what was required in the PPP programme.

- It is also certain to attract a different class of private capital. To be successful in the BOT bids required a proven ability to navigate and manage the system.

- It thus attracted battle-hardened domestic entrepreneurs adept at finding creative ways of extracting value, including through ‘gold plating’ of project costs or through ‘negotiated settlements’ with demanding government inspectors or friendly bankers.

- On the other hand, for success under the bidding process of the NMP, what will be required is operational experience in running a particular class of infrastructure assets and a strong understanding of the potential cash flows generated over the life of the concession.

- This is certain to attract the largest global pension funds.

- The proposed asset sale (monetisation) raises many questions.

- Conceptually, how is it different from disinvestment and privatisation (D-P) practised for the last three decades?

- Since D-P proceeds (revenues) have seriously missed the targets almost every year, how believable are the NMP targets?

- And how are they likely to perform differently?

- Is the NMP a desperate attempt to shore up public finances, after nearly two years of dismal output growth, stagnant tax-GDP ratio despite the steep rise in taxes on petroleum products?

- If so, is such a distress (fire) sale desirable to obtain a “fair value” for public assets?

- Would the market not factor in the dire state of the economy in beating down the prices, as in any distress sale?

- The NMP differentiates “asset monetisation” from “asset sale” by saying: “Asset Monetisation, as envisaged here, entails a limited period license/lease of an asset, owned by the government or a public authority, to a private sector entity for an upfront or periodic consideration”.

- Asset monetisation as defined above is the same as the net present value (NPV) of the future stream of revenue with an implicit interest rate (whether it is a sale or lease of the asset).

- In a footnote, the NMP document further clarifies: “Sale, i.e. transfer of legal ownership of assets is only envisaged in cases such as disinvestment of stake, etc.”

- Again there seems to be conceptual confusion.

- Sale of minority equity does not lead to a change in managerial control.

- Hence, the official attempt to differentiate its initiative from the earlier efforts seems feeble and incorrect.

- Among the key challenges that may affect the NMP roadmap are: lack of identifiable revenues streams in various assets, level of capacity utilisation in gas and petroleum pipeline networks, dispute resolution mechanism, regulated tariffs in power sector assets, and low interest among investors in national highways below four lanes.

- While the government has tried to address these challenges in the NMP framework, execution of the plan remains key to its success.

- Structuring of monetisation transactions is being seen as key.

- The slow pace of privatisation in government companies including Air India and BPCL, and less-than-encouraging bids in the recently launched PPP initiative in trains, indicate that attracting private investors interest is not that easy.

- “Monetisation potential of toll road assets, though being a market-tested asset class with established monetisation models, is limited by the percentage of stretches having four-lane and above configuration. The total length of national highway (NH) stretches with four-lane and above is estimated to be about 23% of the total NH network,” as per the NMP framework. The government has tried to address this with a plan to monetise assets that are four-lane and above.

- The success of the NMP is by no means assured. Bidding out and designing long-term concessions for assets that are already operating requires considerable skill.

- Given the long tenure of these concession agreements, they must be designed to allow for some flexibility so that each party has the opportunity to deal with unforeseen circumstances (such as climate-related disasters) and to prevent needless litigation.

- Contracts must also incorporate clear key performance indicators expected of the private party and clear benchmarks for assets as they are handed over by the government the start of the concession.

- This is key to avoiding disputes about potential additional capital expenditures that might be required to keep the asset operational.

- Two, no matter how well a contract is crafted, it still needs to be implemented effectively.

- Experience shows that there is a tendency for government departments to inject opacity into the implementation of concession agreements so that they have more power over the concessionaire.

- To avoid this, it would be useful if the responsibility for administering the concession agreements did not lie directly with the line ministries and/or their agencies.

- Three, it is vital to put in place a robust dispute resolution mechanism. For all these reasons there is a strong case to set up a centralised institution with the skills and responsibility to oversee contract design, bidding and implementation, separate from, but with appropriate assistance of, the concerned line ministries.

- An institution such as ‘3 PPP India’, first mooted in the 2014 Budget, is needed.

- It would also be advisable to set up an Infrastructure PPP Adjudication Tribunal along the lines of what was recommended by the Kelkar Committee (2015) to create suitably specialised dispute resolution capacity.

- Finally, it is always wise to under-promise and over-deliver.

- The government could start with sectors that offer greatest cash flow predictability and the least regulatory uncertainty before expanding the experiment.

- It could also ensure that resources raised from the NMP are used to fund new asset creation under the National Infrastructure Pipeline. This will ensure credibility.

- As enunciated in the Economic Survey 2020-21, an important step for the Government to take to strengthen public sector businesses would be to completely revamp their corporate governance structure in order to enhance operational autonomy augmented with strong governance practices including listing on stock exchange for greater transparency and accountability.

- The Department of Public Enterprises has reportedly initiated revamping of the performance monitoring system of central public sector enterprises to make them more transparent, objective and forward looking, based on sectoral indices/benchmarks.

- The Economic Survey also highlights the Government’s initiatives as part of the Atmanirbhar Abhiyaan (campaign for self-reliance) in order to boost domestic production in the steel sector, viz. inclusion of “speciality steel”, recommending four different types of steel for incentives under the production linked incentive (PLI) scheme; selling steel to Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs), affiliated to Engineering Export Promotion Council of India at export parity price under the duty drawback scheme of the Directorate General of Foreign Trade (DGFT); measures to provide preference to domestically produced iron and steel in government procurement, where aggregate estimate of iron and steel products exceeds ₹25 crore; protecting industry from unfair trade through appropriate remedial measures including imposition of anti-dumping duty and countervailing duty on the products on which unfair trade practices were adopted by the other countries.

- More such out-of-the-box policy initiatives are needed to rule out public asset monetisation schemes such as the NMP in future.

Related Articles