1st May 2025 (11 Topics)

Mains Issues

Context

In a recent tit-for-tat move, India decided to shut down its airspace to all Pakistan-owned and operated aircraft, after Pakistan first imposed similar restrictions on Indian carriers following escalations over the Pahalgam terror attack.

More on News

- India has deployed advanced jamming systems along its western border to disrupt the Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) signals used by Pakistani military aircraft, significantly degrading their navigation and strike capabilities.

- The Indian jamming systems are capable of interfering with multiple satellite-based navigation platforms, including GPS (US), GLONASS (Russia), and Beidou (China) - all of which are used by Pakistani military craft.

Who Owns and Controls Airspace?

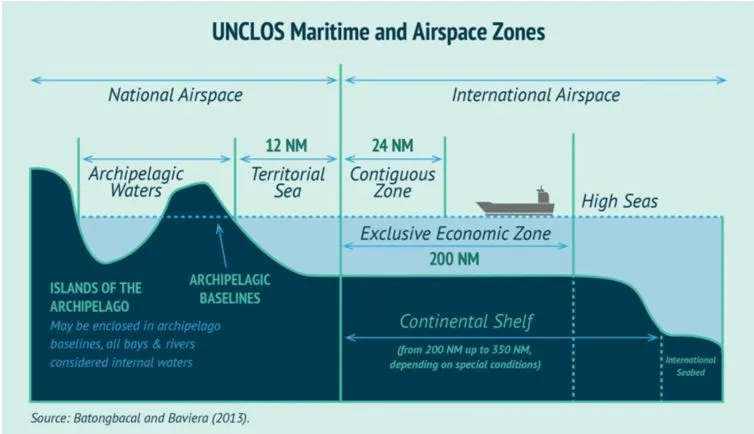

- Under Article 1 of the Chicago Convention (1944), a country has full and exclusive sovereignty over the airspace above its territory — including land and 12 nautical miles from its coastline.

- This means no foreign aircraft can fly over, land, or even transit through a nation’s airspace without prior permission from the concerned government.

- Airspace beyond these territorial limits is considered International Airspace, often managed by global or regional authorities like ICAO, or designated to countries through mutual agreements (e.g., USA managing parts of Pacific airspace).

- Overflight and Landing Permits: When airlines fly from one country to another, they need special permissions known as Flight Permits, which are issued for safety, security, and regulatory compliance:

- Overflight Permit: Required when an aircraft enters, crosses, and exits a country’s airspace without landing.

- Landing Permit: Needed if the flight intends to land or stop at a country’s airport.

- Diplomatic Permit: Compulsory for government or military aircraft, issued through diplomatic channels.

- Each country has its own rules and charges for granting these permits — including navigation fees, landing and parking charges, and terminal charges.

Legal and Regulatory Framework in India

- Directorate General of Civil Aviation (DGCA) is India’s key aviation regulator. It issues permits, ensures safety compliance, registers aircraft, and coordinates with the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO).

- Airports Authority of India (AAI) manages the air traffic control, communication, navigation, and surveillance systems across Indian airspace.

- Flights using Indian airspace — even without landing — pay Route Navigation Facility Charges (RNFC) and other fees. These are determined by DGCA and managed by AAI.

- After the 2017 revision, international flights flying over Indian territory contribute significantly to India’s aviation revenue through these charges.

Mains Issues

Context

The Cabinet Committee on Political Affairs (CCPA) has recently approved the inclusion of caste enumeration in the upcoming population census, reversing the Union government’s previous stand. This comes amid increasing political demand for caste-based data, especially from the Opposition, and growing public discourse around social justice and representation.

What is a Caste Census?

- A caste census involves the enumeration of people based on their caste identity, along with other standard demographic data collected during the decadal Census.

- While data on Scheduled Castes (SCs) and Scheduled Tribes (STs) is already part of every Census post-independence, Other Backward Classes (OBCs) and general caste groups have not been officially counted since 1931.

- India continues to rely on outdated or sample-based estimates (like from the Mandal Commission or National Sample Survey) for assessing the population of OBCs, leading to uncertainty in policy formulation and resource distribution.

- Pre-Independence & Post-Independence Practice

- The last full caste enumeration took place in 1931. In 1941, caste data was collected but not published due to administrative and financial constraints during WWII.

- From 1951 to 2011, the Census has included only SC and ST data, not other caste groups.

- The Socio-Economic Caste Census (SECC) in 2011, conducted alongside the Census but under a different framework, gathered caste data—but that data has never been officially released.

- State caste surveys: Three governments — Karnataka, Telangana and Bihar — have conducted caste surveys so far. Karnataka is yet to release the survey report.

Why is there a demand for Caste Census?

- Legal Necessity: Accurate caste data is crucial for implementing and monitoring reservation policies in education, employment, and political representation. Supreme Court rulings (Indra Sawhney v. Union of India (1992), M. Nagaraj v. Union of India (2006), J.K. Industries Ltd. v. Union of India (2007), State of Uttar Pradesh v. Pradhan Sangh (2008), Vikram Dev Dutt v. Union of India (2022)) have emphasized the need for detailed caste data to uphold and define backward class reservations.

- Data for Targeted Welfare and Representation: Without updated caste data, it's difficult to assess whether reservation policies, welfare schemes, and economic development programs are reaching the right communities. OBCs are estimated to be around 50-52% of India’s population (Mandal Commission), but no official figure exists.

- Need for Evidence-Based Social Justice: Caste remains a powerful determinant of social and economic inequality in India. Many backward caste groups argue that caste data is essential to ensure fair representation in education, employment, and politics.

- State-Level Initiatives: Some states (e.g., Bihar) have already conducted their own caste surveys, creating momentum for a national-level enumeration.

Arguments Against Caste Census

- Risk of Reinforcing Caste Identities: Caste enumeration may further entrench caste divisions, which the Constitution aims to eliminate. They point to the vision of a casteless society championed by Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, warning that formalizing caste data could hinder long-term social cohesion.

- Complexity and Classification Challenges: Issues like overlapping caste names, state-specific variations, and the presence of open-ended or ambiguous categories (like orphans or converts) make data categorization highly challenging.

- Migrants, inter-caste marriages, and regional inconsistencies further complicate the classification process.

- Politicization of Identity: There is concern that caste census data could be misused for vote bank politics, electoral segmentation, and identity-based polarisation, rather than genuine welfare planning.

Fact Box: India’s Caste System

|

Mains Issues

Context

The Supreme Court of India made a landmark declaration that the right to digital access is an intrinsic part of the Right to Life under Article 21 of the Constitution. This judgment came in response to a set of petitions demanding easier digital access for acid attack survivors and visually impaired individuals, particularly in essential services like banking and e-governance.

Key-takeways from the SC’s Judgment

- The two-judge bench stated that:

- In today’s world, access to services and entitlements happens primarily through digital means.

- Digital access is no longer a privilege—it is central to living a life of dignity.

- Therefore, “bridging the digital divide” has become a constitutional imperative, directly linked to the Right to Life and Dignity under Article 21.

- The state’s obligations under Article 21—read in conjunction with Articles 14, 15 and 38 of the Constitution—must encompass the responsibility to ensure that digital infrastructure, government portals, online learning platforms, and financial technologies are universally accessible.

- The Court noted that exclusion from digital services undermines basic rights like:

- Access to welfare schemes

- Financial inclusion

- Legal identity

- Public services (e.g., pensions, subsidies, healthcare)

- Assistive technology: Technology can empower, but only if it is designed with accessibility in mind. The judgment recognizes that AI-driven assistive technologies like Screen readers, voice commands, and gesture recognition, or Alternatives to biometric authentication (e.g., iris scans, text-based OTPs), can open up new possibilities for inclusion.

Digital Divide in India

- Digital India, Ambitious But Unequal: India’s rapid digitisation, via Aadhaar, UPI, e-Governance portals, DigiLocker, Jan Dhan accounts, has enabled vast improvements in transparency and service delivery. However, digital readiness and access are not equal:

- As per NFHS-5 (2019-21), only 33% of women in rural India use the internet.

- PwDs face severe barriers due to non-compatible websites, lack of assistive tech, and inadequate training.

- Legal Identity and Exclusion: Mandatory Aadhaar-based authentication, e-KYC, and biometric requirements have excluded people with disabilities, old-age illnesses, and disfigurements from accessing banking, pensions, and healthcare schemes.

- Lack of Accessibility Norms: Many government websites and apps do not comply with accessibility guidelines (like WCAG 2.0 or GIGW – Guidelines for Indian Government Websites), despite obligations under the Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act, 2016.

Who is affected by the Digital Divide?

- People with disabilities, especially those with visual impairments or disfigurements, often find digital services inaccessible due to reliance on visual interfaces.

- Rural and poor households lack access to devices like smartphones or broadband, making it difficult to access schemes like MGNREGA, PM-Kisan, or banking services.

- Senior citizens and linguistic minorities struggle with digital literacy, user-unfriendly interfaces, and complex verification procedures.

- For instance, a person unable to blink (as required for live photo capture in e-KYC) is denied a bank account, pushing them further into economic marginalisation.

Digital Access and Evolving Rights

- Intersection with Disability Rights: Under the Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act, 2016, the government is obligated to ensure equal access to ICT (Information and Communication Technology) infrastructure, including:

- Accessible digital platforms,

- Reasonable accommodation,

- Assistive technology support.

- Evolving Jurisprudence on Digital Rights: This judgment aligns with recent cases that expanded digital rights, such as:

- Right to internet access as a fundamental right (Anuradha Bhasin case, 2020)

- Right to privacy in digital life (Puttaswamy case, 2017)

- Digital education as a part of the right to education during COVID-19

Fact Box: People with disabilities in India

|

Mains Issues

Context

The Supreme Court of India has clarified that the technical panel’s report on the Pegasus spyware investigation will not be made public, citing concerns over national security and sovereignty. The Court was responding to petitions seeking disclosure and further action over the alleged use of Israeli spyware Pegasus to surveil journalists, politicians, and activists.

Background: What Is the Pegasus Case About?

- In 2021, media reports claimed that Pegasus spyware, developed by Israeli firm NSO Group, was used in India for unauthorized surveillance.

- Alleged targets included civil society members, opposition leaders, and journalists.

- The Supreme Court appointed a three-member technical committee, monitored by Justice R.V. Raveendran, to investigate the matter.

- In August 2022, the Court revealed that malware was found in 5 out of 29 phones, but there was no conclusive proof that Pegasus was used.

What the Supreme Court Said?

- Using spyware is not inherently wrong if it serves national interest; the issue is how and against whom it is used.

- Reports that affect “national security or sovereignty” cannot be made public.

- Individual concerns, such as people who suspect their phones were compromised, can be addressed privately.

- Public discourse cannot be allowed on matters that could compromise national intelligence operations.

Key Legal and Security Dimensions

- Right to Privacy (Article 21) vs. National Security: The case hinges on the balance between privacy rights and the State’s right to safeguard national interests. The Puttaswamy judgment (2017) affirmed privacy as a fundamental right, but allowed restrictions in the interest of national security.

- Judicial Oversight and Transparency: The Court’s refusal to publish the report raises concerns about transparency and accountability in surveillance matters.

- However, it reinforces the idea that courts act as guardians of both individual rights and national security interests.

- Cybersecurity and Tech Sovereignty: The case reflects growing anxieties around digital surveillance, state-sponsored hacking, and the need for a robust cybersecurity legal framework. Pegasus, being a military-grade spyware, raises international legal and ethical concerns.

Prelims Articles

Context

Sri Kanchi Kamakoti Peetham appointed 25-year-old Ganesha Sharma Dravida from Andhra Pradesh as its 71st Acharya, with the monastic name Sri Satya Chandrasekharendra Saraswathi Swamigal, continuing its unbroken spiritual lineage.

About Kanchi Kamakoti Peetham

- Location: Kanchipuram, Tamil Nadu

- The Kanchi Kamakoti Peetham is believed to have been established by Adi Shankaracharya in the 8th century CE.

- Out of the four traditional mathas (monastic institutions) that Adi Shankara is credited with establishing in the four corners of India (Sringeri, Puri, Dwaraka, Badrinath), Kanchi is a later addition, but one that has emerged as a profound centre of scholarship, dharmic leadership, and Vedic revival, especially in South India.

- It has maintained an unbroken spiritual lineage of 71 Acharyas (pontiffs), with each Acharya playing a key role in preserving ritual traditions, teaching Vedanta, and guiding communities in ethical and religious matters.

- The matha has maintained a continuous line of acharyas (pontiffs), each succeeding the previous through a carefully chosen and spiritually trained disciple, often at a young age.

- It is known for:

- Propagation of Sanatana Dharma, Vedic studies

- Preservation of Sanskrit texts

- Social service

Fact Box:About Adi Shankaracharya

|

Prelims Articles

Context

The government has revamped the National Security Advisory Board amid tensions over the Pahalgam terror attack, appointing former intelligence chief Alok Joshi as its chairman.

About NSAB

- The National Security Advisory Board (NSAB) is an advisory body under the National Security Council (NSC) structure of India.

- It is chaired by the Prime Minister and supported by the NSA and the NSCS.

- The NSAB was established in 1998, after the Pokhran-II nuclear tests, as part of the institutionalisation of India’s national security architecture.

- It is not a decision-making body, but it plays a key role in providing long-term, non-partisan, strategic inputs on national security issues.

- The NSAB reports to the National Security Council Secretariat (NSCS), which functions under the National Security Advisor (NSA).

- It comprises experts from defence, intelligence, diplomacy, academia, and civil services.

Prelims Articles

Context

Hydrogen has long been viewed as a clean energy fuel of the future. While much attention has been given to green hydrogen (produced using renewable energy), scientists and industry leaders are now turning to naturally occurring hydrogen — also called white hydrogen — as a potentially abundant, low-cost, and zero-carbon energy source.

What is Natural Hydrogen?

- Unlike grey hydrogen (from natural gas, emits CO?) and green hydrogen (from water via electrolysis using renewables), natural hydrogen occurs freely in the Earth’s crust, formed by natural geological processes such as:

- Serpentinisation: A reaction between water and iron-rich rocks.

- Radiolysis: Breakdown of water by naturally radioactive rocks.

- Organic decomposition: Breakdown of buried organic matter deep underground.

- It seeps out through fractures in the earth or accumulates in underground reservoirs — much like natural gas or helium.

Global Potential

|

Prelims Articles

Context

A new study using Japan's Subaru Telescope has reignited debate over the S8 parameter, which measures how matter is distributed—or clumped—in the universe. Conflicting measurements of S8 have created a major puzzle in cosmology, known as the S8 tension.

What is the S8 Parameter?

- In simple terms, S8 (or Sigma-8) is a statistical measure used by cosmologists to describe how much matter is clumped together in the universe.

- A higher value of S8 means matter (like galaxies and dark matter) is more clustered.

- A lower value means matter is more evenly spread out.

- S8 is especially important because it helps scientists understand how the early universe evolved into the large-scale structure we observe today — galaxies, clusters, voids, and filaments.

Why Is There a Disagreement – The ‘Tension’?

- There are two major methods to estimate S8, and they produce different results:

- Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB) Method: Uses data from early universe radiation — the CMB, emitted just 380,000 years after the Big Bang. This method gives a higher S8 value (more clumpiness).

- Example: Data from Planck satellite gives S8 ? 0.83.

- Cosmic Shear Surveys (Gravitational Lensing): Looks at how light from distant galaxies is distorted by gravitational effects (like a cosmic magnifying glass). These distortions (called cosmic shear) help map current matter distribution, especially dark matter.

- This method gives a lower S8 value (less clumpiness).

- Example: Subaru HSC study estimates S8 ? 0.747.

- This persistent mismatch between early universe predictions and present-day observations is what cosmologists refer to as the “S8 tension”.

- Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB) Method: Uses data from early universe radiation — the CMB, emitted just 380,000 years after the Big Bang. This method gives a higher S8 value (more clumpiness).

Editorials

Context

India has been ranked the world’s largest plastic polluter (Nature journal), releasing 9.3 million tonnes annually, with major data gaps, rural neglect, and unmonitored disposal methods. The Supreme Court’s use of continuing mandamus in the Vellore tannery pollution case highlights a judicial tool that could be extended to India’s systemic waste management crisis.

Data Deficit and Ground-Level Governance Gaps

- Inaccurate Waste Statistics: Official data (0.12 kg/capita/day) underestimates India’s plastic waste generation, as it excludes rural, informal, and open-burning sources; actual rate estimated at 54 kg/capita/day.

- Poor Methodology & Rural Exclusion: CPCB data lacks methodological transparency, with no audit trail; rural India remains excluded from waste accounting under Panchayati Raj Institutions (PRIs).

- Unlinked Waste Infrastructure: Absence of geotagged tracking and lack of systematic connectivity between local bodies and MRFs, EPR kiosks, and sanitary landfills hamper efficient waste processing.

Legal Framework and Supreme Court Intervention

- Constitutional and Statutory Obligations: Waste mismanagement violates Article 21 (Right to Life) and environmental norms under Solid Waste Management Rules, 2016, requiring active court oversight.

- Use of Continuing Mandamus: In the Vellore tannery case (Jan 31, 2024), SC used continuing mandamus, appointed a compliance committee, and recognized the failure of administrative execution despite legal mandates.

- Polluter Pays and Government Pay Principles: Court enforced the “polluter pays” principle, holding polluters and governments liable for both compensation and ecological restoration, till damage is fully reversed.

Way Forward: Technology, Accountability, and EPR Operationalisation

- Leveraging Tech for Waste Mapping: India must use its technological prowess for real-time waste generation and tracking to ensure scientifically grounded infrastructure planning and monitoring.

- EPR Kiosks for Decentralised Recovery: Producers, Importers, Brand Owners (PIBOs) should establish EPR kiosks at the grassroots, ensuring segregation, retrieval, and recycling at source.

- Judicial Oversight for Compliance: Extending the tool of continuing mandamus in environmental cases would ensure time-bound, court-monitored enforcement, especially in waste management reform.

Practice Question

Q. Discuss the significance of the Supreme Court’s use of “continuing mandamus” in addressing environmental degradation. How can this judicial tool be institutionalised to strengthen waste management governance in India?

Editorials

Context

India’s Index of Industrial Production (IIP) growth averaged 4% in FY 2024–25, marking its lowest level in four years, highlighting a broad slowdown in industrial activity amid global uncertainty, weak consumption, and subdued private investment.

Trends in Core Industrial Sectors

- Declining Industrial Growth: The IIP growth fell from 9% in FY24 to 4% in FY25, reflecting deceleration across manufacturing, mining, and electricity sectors.

- Sectoral Dip – Mining and Manufacturing: Mining output dropped steeply from 5% to 2.9%, while manufacturing slowed from 5.5% to 4%, indicating persistent supply chain issues and weak industrial demand.

- Electricity Output Cyclically Supported: Electricity generation rose from 6% (Feb) to 6.3% (Mar) due to seasonal summer demand, though annual growth fell from 7% to 5.1%.

Diverging Consumption Patterns

- Rural Stress – Consumer Non-Durables Degrowth: Consumer non-durables saw a degrowth of -1.6% in FY25 from +4.1% in FY24, driven by strained rural demand due to food inflation and falling farm incomes.

- Urban Resilience – Durable Goods Uptick: Consumer durables grew from 6% to 8%, signaling urban demand recovery, likely supported by lower lending rates and pent-up discretionary spending.

- Inflation Trends – Mixed Impact: Though retail inflation fell to 4.6% (lowest in 6 years), the drop in vegetable prices adversely affected agricultural earnings, further dampening rural consumption.

Exports and MSME Sector Pressure

- Flat Export Growth – MSME Exposure: Goods exports remained flat in FY25, raising concerns about the MSME sector, which contributes nearly 46% to total exports.

- MSME Scale vs. Vulnerability: Despite expanding from Rs 4 lakh crore (FY21) to Rs 12 lakh crore (FY25), MSMEs, especially micro units, remain vulnerable to external shocks and trade disruptions.

- Strategic Trade Leverage – Need for US Pact: India must strategically conclude the Bilateral Trade Agreement with the US, its top trading partner, to safeguard 60 million MSMEs and the 250 million jobs they generate.

Practice Question

Q. Discuss the recent trends in India’s Index of Industrial Production (IIP) with reference to sectoral performance and consumption dynamics. How do these trends reflect the broader economic stress in MSMEs and export sectors?

Editorials

Context

India, aiming for net-zero emissions by 2070, is significantly behind its National Forest Policy target of 33% forest and tree cover (currently at 25.17%). With accelerating climate change and external carbon regulations (like EU’s CBAM), afforestation and carbon sequestration are becoming strategic tools for environmental, economic, and trade resilience.

Environmental and Policy Dimensions

- Forest Cover Deficit: India’s forest and tree cover is 17%, far below the 33% target of National Forest Policy, 1988, raising concerns over ecological sustainability and carbon sink capacity.

- Policy Initiatives and Green Missions: Key programmes include the Green India Mission (under NAPCC), which increased forest cover by 56% (2017–21), and the National Agroforestry Policy (2014) that promotes tree plantations outside traditional forests.

- Agroforestry and Rural Sustainability: Agroforestry enhances soil fertility, water retention, and income diversification, with 20–30% increase in farm income as per ICAR, thereby aligning ecological benefits with rural livelihood enhancement.

Industrial Strategy and Trade Implications

- Industry-Driven Afforestation via CSR and Carbon Credits: Industries are investing in tree plantations to generate carbon credits under the Verified Carbon Standard and CDM, as a cost-effective alternative to buying expensive EU credits (avg. €83/tonne CO? in 2023).

- Global Trade Pressures and CBAM Impact: EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), effective 2026, poses tariff threats on high-emission goods like cement and steel, pushing Indian exporters to reduce carbon footprints via afforestation.

- ESG and Competitive Advantage: Sustainability is now a strategic business imperative, with green supply chains, carbon offsetting, and ESG compliance crucial to attracting global investment and securing export markets.

Carbon Policy Reform

- High Cost of Global Carbon Credits: With EU carbon credits averaging €83/tonne, afforestation offers a cost-effective domestic alternative for industries to meet emission obligations and avoid trade penalties.

- Lack of National Carbon Market Framework: India lacks a transparent carbon credit registry, Article 6-compliant trading mechanism, and financial incentives, hindering private sector afforestation investments.

- Need for Institutional and Community Participation: To achieve large-scale afforestation, India needs community-led models, training & market support, and robust monitoring, aligning environmental outcomes with socio-economic co-benefits.

Practice Question

Q. Tree plantations are emerging as a key strategy for climate mitigation, rural development, and industrial competitiveness in India. Critically evaluate the ecological, economic, and policy challenges in implementing afforestation at scale in India.