The Tribunals Reforms Act is a much-awaited initiative by the Central Government to improve the tribunal framework of the country. Although the Act suffers from certain flaws. Government should ensure the independence of the tribunals to preserve the basic structure of our Constitution and eliminate the threat to the doctrine of separation of power.

In 1976, Articles 323A and 323B were inserted in the Constitution of India through the 42nd Amendment.

- Article 323A empowered Parliament to constitute administrative Tribunals (both at central and state level) for adjudication of matters related to recruitment and conditions of service of public servants.

- Article 323B specified certain subjects (such as taxation and land reforms) for which Parliament or state legislatures may constitute tribunals by enacting a law.

In 2010, the Supreme Court clarified that the subject matters under Article 323B are not exclusive, and legislatures are empowered to create tribunals on any subject matters under their purview as specified in the Seventh Schedule of the Constitution.

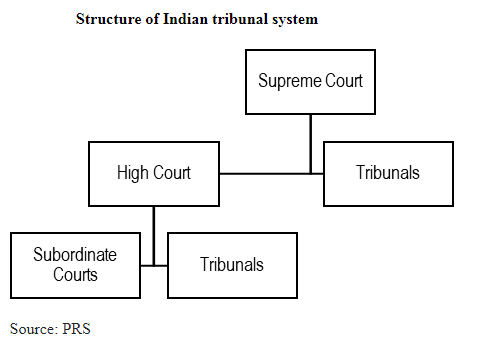

Currently, tribunals have been created both as substitutes to High Courts and as subordinate to High Courts). In the former case, appeals from the decisions of Tribunals (such as the Securities Appellate Tribunal) lie directly with the Supreme Court. In the latter case (such as the Appellate Board under the Copyright Act, 1957), appeals are heard by the corresponding High Court.

|

Difference between judicial and quasi-judicial The judicial and quasi-judicial acts differ from each other as the judicial acts require a proper proceeding of the court and the judge is duty-bound whereas the quasi-judicial acts don't require the courts and decisions taken under them are by the person, who is not a judge. |

- As a quasi-judicial body, the Tribunal performs the judicial functions for deciding the matters in a judicious manner. It is not bound by law to observe all the technicalities, complexities, refinements, discriminations, and restrictions that are applicable to the courts of record in conducting trials.

- Tribunal is required to look at all matters from the standpoint of substance as well as form and be certain that the hearing is conducted and the matter is disposed of with fairness, honesty, and impartiality.

- In the procedural matters, an administrative tribunal possesses the powers of a court to summon witnesses, to administer oaths and to compel the production of documents, etc.

- These tribunals are bound to abide by the principle of natural justice.

- The prerogative writs of certiorari and prohibition are available against the decisions of administrative tribunals.

The Act seeks to dissolve certain existing appellate bodies and transfer their functions (such as adjudication of appeals) to other existing judicial bodies, further it has brought changes in the term of office and other provisions.

Chronology of events

- In March 2017, the Finance Act, 2017 re-organized the tribunal system by merging tribunals based on functional similarity. The total number of Tribunals was reduced from 26 to 19. It delegated powers to the central government to make Rules to provide for the qualifications, appointments, term of office, salaries and allowances, removal, and other conditions of service for chairpersons and members of these tribunals.

- In November 2019, the Supreme Court struck down the 2017 Rules. The Court stated that the Rules did not meet the requirements laid down in earlier judgements mandating judicial independence in terms of: (i) composition of the Tribunals, (ii) the security of tenure of the Tribunal members, and (ii) composition the search-cum-selection committees.

- The Court directed the central government to reformulate the Rules. Key concerns that the Court wanted addressed include: (i) short tenures which prevent enhancement of adjudicatory experience, and thus impact the efficacy of Tribunals, and (ii) lack of judicial dominance in selection committees which is in direct contravention of the doctrine of separation of powers.

- In February 2020, new Rules were notified, which were again challenged in the Supreme Court mainly over the lack of conformity with the principles laid out earlier by the Court.

- The Court suggested certain amendments to the 2020 Rules such as increasing the term of office to five-year along with eligibility for re-appointment (subjected to upper age limits), and allowing advocates with 10 years’ experience to be appointed as judicial members.

- However, government has passed the Act in 2021.

The provisions of the Act are discussed below:

- Abolishing of appellate bodies and transfer of functions: It abolishes certain appellate bodies and transfer their functions to existing judicial bodies.

|

Transfer of functions of key appellate bodies as proposed under the Bill |

||

|

Acts |

Appellate Body |

Proposed entity |

|

The Cinematograph Act, 1952 |

Appellate Tribunal |

High Court |

|

The Trade Marks Act, 1999 |

Appellate Board |

High Court |

|

The Copyright Act, 1957 |

Appellate Board |

Commercial Court or the Commercial Division of a High Court* |

|

The Customs Act, 1962 |

Authority for Advance Rulings |

High Court |

|

The Patents Act, 1970 |

Appellate Board |

High Court |

|

The Airports Authority of India Act, 1994 |

Airport Appellate Tribunal |

|

|

The Control of National Highways (Land and Traffic) Act, 2002 |

Airport Appellate Tribunal |

Civil Court# |

|

The Geographical Indications of Goods (Registration and Protection) Act, 1999 |

Appellate Board |

High Court |

- Amendments to the Finance Act, 2017:The Finance Act, 2017 merged tribunals based on domain. It also empowered the central government to notify rules on: (i) composition of search-cum-selection committees, (ii) qualifications of tribunal members, and (iii) their terms and conditions of service (such as their removal and salaries). The Bill removes these provisions from the Finance Act, 2017. Provisions on the composition of selection committees, and term of office have been included in the Bill. Qualification of members, and other terms and conditions of service will be notified by the central government.

- Search-cum-selection committees:The Chairperson and Members of the Tribunals will be appointed by the central government on the recommendation of a Search-cum-Selection Committee.

The Committee will consist of:

- the Chief Justice of India, or a Supreme Court Judge nominated by him, as the Chairperson (with casting vote),

- two Secretaries nominated by the central government,

- the sitting or outgoing Chairperson, or a retired Supreme Court Judge, or a retired Chief Justice of a High Court, and

- the Secretary of the Ministry under which the Tribunal is constituted (with no voting right).

State administrative tribunals will have separate search-cum-selection committees. These Committees will consist of:

- the Chief Justice of the High Court of the concerned state, as the Chairman (with a casting vote)

- the Chief Secretary of the state government and the Chairman of the Public Service Commission of the concerned state,

- the sitting or outgoing Chairperson, or a retired High Court Judge, and

- the Secretary or Principal Secretary of the state’s general administrative department (with no voting right). The central government must decide on the recommendations of selection committees preferably within three months from date of the recommendation.

- Eligibility and term of office:The Bill provides for a four-year term of office (subject to the upper age limit of 70 years for the Chairperson, and 67 years for members). Further, it specifies a minimum age requirement of 50 years for appointment of a chairperson or a member.

Critical analysis

- Rationalization of Tribunals: Government Data from the past three years shows that the presence of tribunals in certain sectors has not led to faster adjudication, and such tribunals add considerable cost to the exchequer. Take for example the Intellectual Property Appellate Board (IPAB), a body meant to perform a salutary function in this time and age. The IPAB mostly remained non-functional during its lifetime, leaving litigants neither here nor there. Some tribunals are located at far off places while courts are available at the doorsteps of litigants and in case of the High Court, within the State.

Some tribunals face the issue of a large backlog of cases. For example, as of March 15, 2021, the central government industrial tribunal cum-labour courts had 7,312 pending cases; as of February 28, 2021, the Armed Forces Tribunal had 18,829 pending cases; and as of January 1, 2018, the Income-tax Appellate Tribunal had 91,643 pending cases.

The lack of human resources (such as inadequate number judges) is observed to be one of the key reasons for accumulation of pending cases in courts. The Standing Committee on Personnel, Public Grievances, Law and Justice (2015) had noted that several tribunals (such as Cyber Appellate Tribunal and Armed Forces Tribunal) have vacancies which makes them dysfunctional. As of March 3, 2021, there were 23 posts vacant out of total 34 sanctioned strength of judicial and administrative members in Armed Forces Tribunal.

However, on the flip side, transferring functions of an appellate body to a High Court may lead to a further increase in the disposal time of cases as most High Courts already have high pendency. Note that as of July 20, 2021, there are over 59 lakh cases pending in High Courts across India. This defeats the purpose with which these tribunals were set up, which was to help reduce the burden on High Courts. Further, if there is an issue of shortage of administrative capacity at such tribunals, it may be questioned whether the capacity should be increased, or their case load be shifted to other courts.

- Judicial independence - As the tribunals are vested with judicial powers, there must be a security in tenure, freedom from ordinary monetary worries, freedom from influences and pressures within (from others in the Judiciary) and without (the Executive). Once the judiciary is manned by people of unimpeachable integrity, who can discharge their responsibility without fear or favour, the objective of independent judiciary will stand achieved.

However, the Act specify that the term of office for the Chairperson and members will be four years. Supreme Court stated objection in such provision. The Court stated that specifying four years of term of office violates the principles of separation of powers, independence of judiciary, rule of law, and equality before law.

Over the years, the Supreme Court had stated that short tenure of members of a tribunal along with provisions of re-appointment increases the influence and control of the Executive over the judiciary. It also discourages meritorious candidates from applying for such positions as they may not leave their well-established careers to serve as a member for a short period. The Court has also noted that security of tenure and conditions of service (including adequate remuneration) are core components of independence of the judiciary. The Supreme Court had stated that the term of office for the Chairperson and other members must be five years (subject to a maximum age limit of 70 years for the Chairperson and 67 years for other members).

- Equal opportunity in appointment system - Since the Tribunals are entrusted with the duty of adjudicating the cases involving legal questions and nuances of law, adherence to principles of natural justice will enhance the public confidence in their working. The Judicial Member should be a person possessing a degree in law, having a judicially trained mind and experience in performing judicial functions.

The Act specify that a person must be at least 50 years old to be appointed as a member of a tribunal. This violates past Supreme Court judgements. It reiterated earlier judgements which emphasized the recruitment of members at a young age. In past judgements, the Supreme Court (2020) has stated that advocates with at least 10 years of relevant experience must be eligible to be appointed as judicial members, as that is the qualification required for a High Court judge. A minimum age requirement of 50 years may prevent such persons from being appointed as tribunal members.

- Search-cum-Selection Committee: While the Bill provides for uniform pay and rules for the search and selection committees across tribunals, it also provides for removal of tribunal members. It states that the central government shall, on the recommendation of the Search-cum-Selection Committee, remove from office any Chairperson or a Member, who—

(a) has been adjudged as an insolvent; or

(b) has been convicted of an offence which involves moral turpitude; or

(c) has become physically or mentally incapable of acting as such Chairperson or Member; or

(d) has acquired such financial or other interest as is likely to affect prejudicially his functions as such Chairperson or Member; or

(e) has so abused his position as to render his continuance in office prejudicial to the public interest.

Chairpersons and judicial members of tribunals are former judges of High Courts and the Supreme Court. While the move brings greater accountability on the functioning of the tribunals, it also raises questions on the independence of these judicial bodies.

In the Search-cum-Selection Committee for state tribunals, the Bill brings in the Chief Secretary of the state and the Chairman of the Public Service Commission of the concerned state who will have a vote and Secretary or Principal Secretary of the state’s General Administrative Department with no voting right. This gives the government a foot in the door in the process. The Chief Justice of the High Court, who would head the committee, will not have a casting vote

Further the Act created a controversy between legislature, judiciary and Executive. Let us understand the Act from this point of view.

- Legislature vs Judiciary

- The Act was introduced in the lower house of the Parliament only a few days after the Supreme Court, in the Madras Bar Association(2021), struck down certain provisions of the Tribunal Reforms (Rationalisation and Conditions of Service) Ordinance, 2021, a predecessor to the Act with similar provisions. The present Act has been passed by the legislature as an attempt to reverse the judicial pronouncement by re-enacting the provisions which were struck down by the Supreme Court. To circumvent the restrictions imposed by the Madras Bar Association (2021) case, the legislature added a non-obstante clause under Section 3(1) of the Act, with respect to the condition of service of members of tribunals. It states: “Notwithstanding anything contained in any judgment, order or decree of any court, or in any law for the time being in force”.

Thus, the Act has nullified the ruling in the Madras Bar Association case. Thereby, divesting the judiciary of its innate power to keep a check on the power of the legislature and diluting the doctrine of separation of powers.

Executive versus Judiciary

- Article 50 of the Constitutionprovides for the separation of judiciary from executive power. The present Act undermines this principle in many ways and thus, results in encroachment of executive in the judicial domain. Section 3(3) of the Act provides for the composition of Search-cum-selection Committee. Such composition is in consonance with the judicial guidelines in Madras Bar Association (2021), and hence maintains judicial dominance in appointments matter. However, Section 3(8) of the Act may render this feature of judicial dominance otiose. It states – “No appointment shall be invalid merely by reason of any vacancy or absence of a Member in the Search-cum-Selection Committee”.

It flows from this subsection that the appointments may proceed even in case of the total absence of members from the judiciary. By way of this provision, the executive may exercise primacy over the judiciary in the Committee concerned with judicial appointments. Moreover, the provisions dealing with tenure and age restrictions of members could be viewed as another form of executive control in tribunal appointments.

Further, as opposed to prior judicial rulings, Section 3(7) states that the Search-cum-selection committee shall recommend a panel of two names for each position and the subsequent selection will be at the discretion of the Central Government. As a result of which it has been directed by the Supreme Court at various instances that the committee shall recommend only one name for each position. While doing so, the court noted that “executive influence should be avoided in matters of appointments to tribunals”. However, due to the operation of the non-obstante clause, the government has chosen to ignore any such directions.

Related Articles