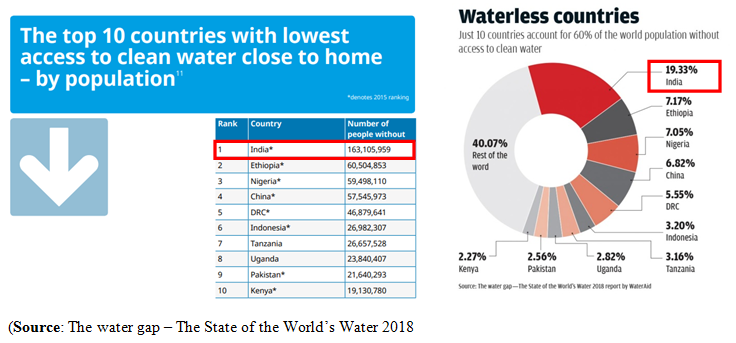

A WaterAid report named State of the World’s Water 2018, ranked India on the top of 10 countries in the world with 163.1 million inhabitants living without access to safe water close to home.

The global commitment to safe water for all is further demonstrated through the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 6 target to achieve universal and equitable access to safe and affordable drinking-water for all.

Privatization of water - World Bank and IMF have suggested privatization of water, based on multiple successful examples of water privatization in different parts of the world, including Gulf countries, Latin American as well as European countries. However, India has not formally considered this idea nor there has been any private sector regulation act or rules to regulate the functioning of the private sector. In this context, National Water Framework Law (NWFL) states that, “water is the common heritage of the people of India; an inseparable part of a people’s landscape, society, history and culture; and in many cultures, a sacred substance, being venerated in some as a divinity”. Such a resource therefore, must never be privatized. Private extraction of groundwater happened in a competitive race to get water from greater and greater depths. Thus, when groundwater is treated as a private resource, it raises a serious issue of destructive competitive extraction. A classic example is that of a soft drinks giant depriving the people of gram panchayat Plachimada in Kerala access to drinking water.

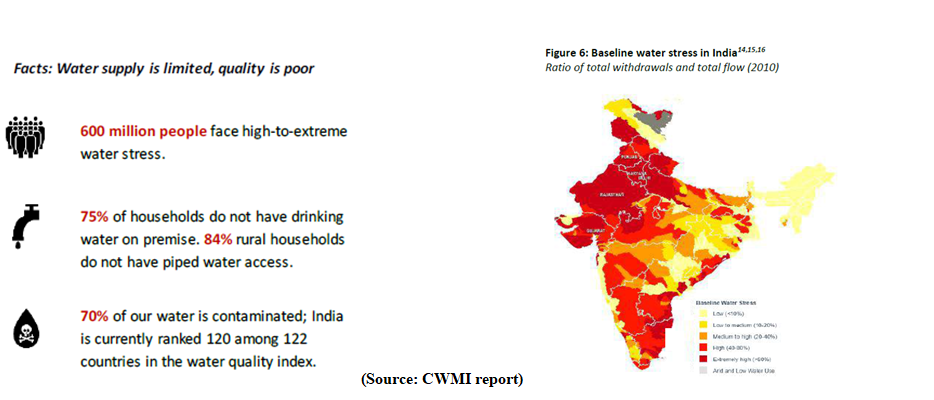

- About 75% of Indian households do not have drinking water at their premise. As a result, 200,000 people die every year due to inadequate access to safe drinking water, 84% of rural households do not have piped water access and that 70% of our water is contaminated.

- India is currently ranked 120 among 122 countries in the water quality index.

- By 2030, demand will be double of the current supply and 40% of the population will not have access to drinking water.

- As per NITI Aayog’s Composite Water Management Index (CWMI)report, a persistent water crisis will lead to an eventual 6% loss in the country’s GDP by

- While more than 90% of the urban population has access to basic water, by 2020, 21 major cities are expected to run out of groundwater affecting 100 million people, including all the metro cities.

- 67% of Indian households do not treat their drinking water, even though it could be chemically or bacterially contaminated

- Two recent studies—“Capturing Synergies Between Water Conservation and Carbon Dioxide Emissions in the Power Sector”and “A Clash of Competing Necessities” point out that India, along with China, France and the US, will have be no drinking water by 2040 if consumption of water continues at the current pace.

- A recent UN report on water conservation reports that due to its unique geographical position, India will face the brunt of the crisis by 2025 and would be at the centre of this global conflict.

Data from the World Bank also highlights India’s plight:

- 163 Million Indians lack access to safe drinking water

- 21% of communicable diseases are linked to unsafe water

- 500 children under the age of five die from Diarrhoea each day in India

Let us now analyse the sources of drinking water in India and the reasons for shortage of drinking water

Some of the crucial issues faced by the water sector in India include

- Poor Administrative Management: Decreasing water quality due to poor waste management laws, growing financial crunch for development of resources and scarcity of safe drinking water. Inadequate institutional reforms and ineffective implementation of existing provisions affect the performance level for water service delivery.

- Inter-state river disputes: Several inter-state river-water disputes have erupted since independence in the backdrop of unsustainable development and increasing population. Water disputes abound within the country and among its neighbors. Despite of explicit constitutional provisions that govern inter-state water disputes, it is unclear whether existing mechanisms for adjudicating interstate water disputes are efficient. Under Inter-State water disputes Act, 1956, numerous tribunals have been set up. Some of the important disputes and Tribunals worth mentioning are:

- The Krishna-Godavari water dispute among Maharashtra, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh (AP), Madhya Pradesh (MP), and Orissa

- The Mahadayi Water Tribunalpronounced its final verdict in August 2018 and permitted Karnataka state to use water outside the basin for drinking water use.

- The Cauvery Water dispute: In the recent years, the Cauvery water dispute has escalated to become a fight over potable drinking water between the two mega cities Bengaluru and Chennai, both facing the worst water crisis in the country. Cauvery water Tribunal was dissolved in 2018 after the disputes among the four riparian states – Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, Kerala and reached finality. Cauvery delta is one of the oldest and largest in the country and supplies drinking water to 20% of the total population of Tamil Nadu.

Water disputes have a potential impact on the overall economy, socio-cultural fabric, political stability, and security of not only the regions in which they occur, but also affect the entire country. However, the current solutions treat only the symptoms and not the root cause of the problem. Inter-State water Disputes Amendment Bill, 2017 has been introduced to speed up the dispute resolution process. As per the bill, Single Permanent Tribunal is to be set up which will have multiple benches.

3. Pollution: The quality of drinking-water is a powerful environmental determinant of health. Water pollution has reached an alarming level in India and has contributed to water scarcity by polluting freshwater resources, thereby limiting options.

River Pollution: Despite Namami Gane, water quality of Ganga continues to worsen. The waters of the Yamuna, Ganga and Sabarmati flow the dirtiest with a deadly mix of pollutants both hazardous and organic. India’s rivers have high fluoride content and are also contaminated by antibiotics, beyond the permissible limit of 1.5 ppm, which affects 66 million people nationwide. The Ganga river basin that covers 26.3% of India’s Geographic area cannot be used for any purpose, including drinking, cooking or bathing. As per the World Water Development Report, 2019, it has been revealed that coliform bacteria and biochemical oxygen demand (BOD) have increased significantly in the Ganga river Because the rivers are too polluted to drink and the government is unable to deliver freshwater, many urban dwellers are turning to groundwater, leading to its rapid depletion.

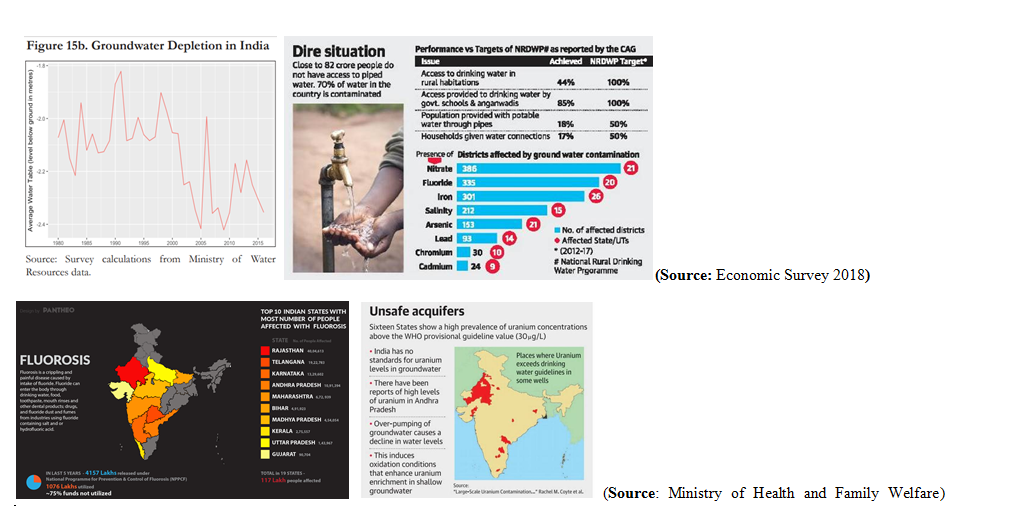

Groundwater (GW) Pollution: India is the largest consumer of GW in the world. As per the Department of Drinking Water and Sanitation (DDWS) nearly 90% of the rural water supply is from GW sources. However, high levels of Arsenic and Fluoride are found in the states of UP where around 78% of population lives in rural areas and are dependent on GW for drinking, cooking and irrigation. Government data revealed that over 45 million are affected with groundwater contaminated with fluoride, arsenic, iron, salinity, nitrate and heavy metal. The World Water Development Report has revealed that India extracts almost one fourth of total groundwater extracted globally

Apart from rivers and ground water, many other water sources are contaminated with both bio and chemical pollutants, and over 21% of the country's diseases are water-related. Recently, in February 2019, a report from International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD) stressed that India, Bangladesh, Pakistan, and China together account for more than 50% of the world’s groundwater withdrawals.

4. Inter-sectoral conflicts: Reliability on water to cool the power plants is one of the largest sources of water withdrawals. Water demand in both Agriculture and Power sector is set to increase tremendously in the coming years.

5. Inefficiency and lack of infrastructure: Water storage infrastructure in India remains one of the lowest in the world. There is also a marked absence of adequate number of well-equipped and functioning sewage treatment plants

6. Climate-Change: Erratic distribution of rainfall, often leading to floods and drought impact drinking water supply. Future predictions include worsening of the situation due to a disturbed hydrological cycle and regional climatic variability.

7.Lack of local Community Participation: Policies and systems are designed and constructed with little participation from local communities.

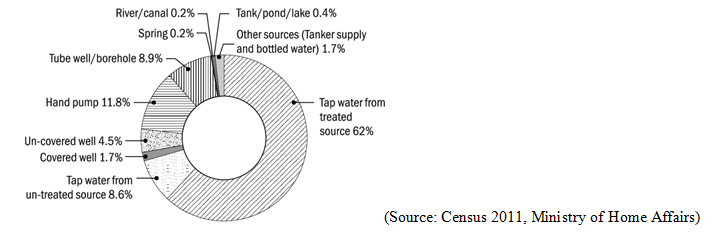

Drinking water in India is extracted from multiple sources across the country.

North India: In the arid regions of North India, groundwater is often the only source of drinking water. India possesses about 432 bcm of groundwater replenished yearly from rain and river drainage, but only 395 bcm are usable, out of which, about 82% goes to irrigation and agricultural purposes. Shimla is facing a major water crisis with limited access to water through tankers for drinking and livelihood purposes. As a result, schools remained closed and tourists were asked to stay away.

West India: The quest for access to clean water sources has led to extensive groundwater extraction in West India. Maximum depletion has been witnessed around Rajasthan, Haryana, Punjab, Gujarat, Telangana and Maharashtra. Latur area of Maharashtra witnessed drought in 2017, however, very little has changed on the ground. Sugarcane cultivation which is heavily dependent on groundwater for irrigation has not seen any major policy overhaul, neither has micro-irrigation practises such as drip or sprinklers been adopted.

Vows of drought prone Krishna basin

Inter-basin transfer is the massive diversion of water from the dry and drought-prone Krishna river basin in western Maharashtra to the high-rainfall Konkan region of coastal Maharashtra. While people in the Krishna basin suffered from recurring droughts and increasing difficulties in accessing safe drinking water, water was been diverted from to generate power for the city of Mumbai. Although in May 2016, Mumbai High Court announced a reversal of this inter-basin transfer, but no steps have been taken in that direction.

South India: Major cities including Chennai, Mysuru and Bengaluru are going through severe drinking water scarcity affecting both day-to-day life and Tourism. The scarcity is attributed to non functional bore-wells, inefficient water management, erratic weather patterns and insufficient supply to meet the excessive needs.

Living without water in Chennai

Following failure of monsoon, depleted groundwater table and dry reservoirs have led to Chennai facing its worst water crisis. The local bodies are facing challenges in supplying drinking water on a daily basis and residents rush with buckets to store water from tankers for entire week. Due to severe water shortage for drinking and livelihood purposes, the city’s everyday life has come to a standstill, schools and hospitals have been badly affected, and industrial sectors have been slowed down. Dry reservoirs and major sources of water are making Chennai dependent on other water sources, such as stone quarries, agriculture wells, Neyveli corporation mines, etc

The State government plans to bring 10 million litres of water from Vellore by rail wagons and from Veeranam lake, which gets Cauvery water from the Mettur dam. There are also plans to write to the Kerala government requesting it to supply 2 MLD every day. Hence, neighboring states’ cooperation along with Central assistance holds critical importance in bringing the city’s water adequacy back to its optimal level.

Bengaluru’s Imminent Water Crisis – A victim of misplaced priorities

A city once known for its lakes, Bengaluru’s sources of safe drinking water have drastically shrunk. Absence of any word of caution from the Cauvery Tribunal has made matters worse. Instead, precious water was transferred from small towns and villages to this megacity hailed globally for its impressive strides in the IT and start-up space. A recent report highlighted that Bengaluru could be doomed, like Cape Town in South Africa, to face the threat of running out of drinking water. Bengaluru, despite not being in the Cauvery basin, has been awarded a total of 4.75 TMC (thousand million cubic feet) of water annually to meet the drinking water needs of its burgeoning urban population

East India: Although relatively less severe than North or West India, the drinking water sources in North Bihar, Jharkhand and West Bengal have also started to witness rapid decline. An estimated 5 million people are likely to be consuming water with concentrations of Arsenic greater than the national standard of 50µg/l, principally in West Bengal.

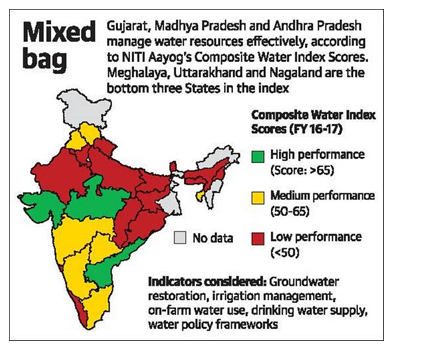

India is clearly reeling under a sustained water crisis that shows no signs of abating. In this context, NITI Aayog’s Composite Water Management Index Report highlights the performance of major cities and ranked the states based on their water management capacity.

NITI Aayog’s Composite Water Management Index Report - Performance of the states

India states have performed averagely on providing safe drinking water. As per the report, Gujarat topped the list in water management, closely followed by Madhya Pradesh and Andhra Pradesh. However, the lowest performers such as UP, Haryana, Bihar and Jharkhand are home to nearly half of India’s population. While Jharkhand and Rajasthan may have scored low, they have made remarkable improvements when compared over two years.

As per the Census 2011, Punjab is ranked the highest based on the percentage of households with access to safe drinking water while Kerala has the worst rank with 33.5% households having access.

For the drinking water to be of greatest purity, every government enforces standards which classify certain qualities of water as usable and the others as non usable. Indian government has recognized these standard guidelines and put them as a part of legal framework. (Indian Standard Drinking Water Specification (BIS 10500: 1991). UNICEF is also supporting GOI programs on arsenic and fluoride mitigation. National Water Policy also clearly establishes that provision to provide adequate and assured safe drinking water is of utmost priority in the country.

- New ‘Jal Shakti’ Ministry: The new ministry formed by merging the Ministry of Water Resources, River Development and Ganga Rejuvenation and Ministry of Drinking Water and Sanitation has promised to ensure potable, piped drinking water to every home by 2024. This move aims at improving India’s structural water crisis that requires sustainable long term policies. As water is a State subject, providing water for drinking is the responsibility of the state.

- River Inter-linking program: A brainchild of former Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee, government in its 2019 election manifesto promised to ensure a long term solution to the problems of drinking water and irrigation. However, environmentalists are concerned over its impacts such as massive displacement of people, expensive affair, and affect the entire ecosystem of the surrounding area.

- Increased Community Participation: World Bank-supported projects have shown that communities are indeed capable of managing their water supply services, if some facilitation is done by local governments. Some of the success stories of states on water management are worth mentioning:

- Mission Kakatiya (Telangana): The mission entails the comprehensive revival of over 40,000 tanks in the State which has led to visible improvements in groundwater levels. It has become a major success despite lack of central funds and becomes a global attention.

- Jalanidhi (Kerala) provided a dependable supply of piped water to 192,000 rural homes in 13 districts

- Swajal (Uttarakhand): Over 8,000 habitations built their own water supply systems. Thus, strong community involvement reduced the cost of systems, rural homes received 24/7 water supply through gravity-based piped systems

- Jal Swarajya (Maharashtra) has brought clean drinking water into 1.2 million homes, more than half of whom were below the poverty line.

- Jal Nirmal (Karnataka): By decentralizing services to rural communities, the Karnataka Jal Nirmal project(2002-2013) improved water supply for about 7 million rural inhabitants in 11 districts of Northern Karnataka.

Waterman of India

Ramon Magsaysay awardee Rajinder Singh is a well known water conservationist and environmentalist. He is credited with harvesting rain water for drinking and domestic purposes by building check dams in Alwar and nearby districts of Rajasthan. The idea was to revive the use of traditional technology of Johad, an ancient water conservation technique to replenish the water sources. Johad is a concave structure that collects and stores water throughout the year for drinking purposes by humans and cattle. It is the successful implementation of this ancient innovation that earned him the name 'Jal Purush' or the 'Waterman of Rajasthan'. The sincere efforts of ‘Waterman’ for eradicating drinking water scarcity in the rural areas of Rajasthan inspired many NGOs within the country and abroad. The transformation was visible and long term. Now, women need not walk for miles to fetch water, neither do men have to leave their homes for work, as the land under cultivation in villages have increased manifold and farm incomes have been on a rise. He also played an instrumental role in revitalization of five rivers that had gone dry for long time.

Bunker Roy – A mix of Technology and Tradition

Bunker Roy is an Indian social activist and educator who founded the Barefoot College. It is based in Tilonia, which is a small village in Rajasthan. What makes this college unique is that it believes in identifying and using skills, knowledge and practical experience of ordinary people in the community itself to provide for basic needs such as drinking water. The College takes men, women and children who are illiterate and semi-literate from the lowest castes, and from the most remote and inaccessible villages in India, and trains them at their own pace to become “barefoot” water and solar engineers.

A hundred year old traditional method to collect rain water through roofs with low cost materials came to the rescue. Economically it is cheaper and the village committee could be empowered to control and distribute the water without being dependent on the outside for any technical, human and financial resource. The college confidently rejects the outside professionals and does not believe in technology that deprives people of their jobs, increases dependency and leads to exploitation. They believe that the mindset of the technological engineers is that problems of water shortage and drinkability can only be solved if expensive and deep well drilling rigs exploit the ground water or pump water from a permanent water source through pipes. However, people of the Tilonia village rejected the idea and instead resorted to simpler cost effective solutions. The college’s staggering achievements include regular piped water supply systems to atleast 10 villages around Tilonia designed and implemented entirely by the local people.

Ralegan Siddhi - A Case Study

Raleghan Siddhi is in a drought-prone and rain-shadowed area of India which faced a severe water crisis that resulted in people having to struggle to find drinking water during part of the year. IN 1975, Anna Hazare who had once lived in the village, returned, determined to improve the situation of the country. He began to involve the community and especially the youth. In order to bring back water, he undertook projects with the villagers to construct nalla bunds, install boreholes and hand-pumps to provide drinking water. The village does not any longer have to worry about having drinking water year round, and the woman no longer have to walk long distances to fetch water.

- Addressing issues of river contamination and sewage treatment would require a decentralized approach by bringing in Local governments, NGOs, private bodies and most importantly citizens’ participation. Unless the citizens do not realize a sense of ownership and responsibility to jointly safeguard water quality, addressing problems of drinking water and water induced diseases would be impossible. Government needs to put in sustained efforts for creating public awareness and vigilance, building consensus about unfair practices and evoking relevant stringent rules, laws and framework around water safety.

- The impact of climate change is significantly larger for the water sector. Therefore newer strategies have to be evolved to achieve a sustainable trajectory of growth and development.

- Privatisation of water: private sector efficiency can be harnessed with structures ensuring accountability, leading to sustainable development. The involvement of the private operator, who will bring in the investment, would ensure long-term commitment to the cause.

- India should note the efforts of countries like Israel and Singapore for sustainable water consumption in their implementation of drip irrigation and desalination plants.

- Encouraging adoption of traditional water conservation methods such as Ahar Pyne and Khadin and knowledge of traditional herbs as water purifying agents along with increased participation of local communities and devolution of power.

- Practices such as Rain water harvesting, Micro irrigation methods such as drip and sprinklers need to be easily accessible at a subsidized rate for the farmers to ease the burden on drinking water sources. Economic Survey of 2018 noted that “Technologies of drip irrigation, sprinklers, and water management—captured in the “more crop per drop” campaign—may well hold the key to future Indian agriculture (Shah Committee Report, 2016; Gulati, 2005) and hence should be accorded greater priority in resource allocation.”

- Some of the country’s major urban conglomerates are reeling with massive water crisis. Do you agree? How far do you think that the reasons for drinking water shortage in the country are more of political nature than environmental nature? Justify your stand with examples. Also evaluate key areas of improvement in your opinion with a way forward.

- India uses one-fourth of groundwater extracted globally. In the light of the UN report, analyse the reasons for the unprecedented extraction of groundwater in India and its immediate and long term impact. Critically examine the role that government and non-governmental organisations have played in dealing with the water crisis in the country. Give relevant examples / case studies.

- Most of the freshwater sources in India are polluted and therefore unfit for drinking purposes. Critically examine the different sources of water and their distribution in the country. How far have inter-state disputes and Namami Gange Program helped in solving the water crisis for states? What other steps (Government and Private) have been taken to improve the present water shortage situation.

- How critical is the present situation of water crisis in India? Justify your stand with relevant data. How far can traditional methods prove helpful in dealing with this crisis? Evaluate the success of non-governmental efforts in dealing with the issue. Also suggest strategies and sustainable solutions to combat with the situation.

- There has been no permanent solution to drinking water crisis in India. Do you agree? How far can environmental issues and erratic monsoon be blamed for the water shortage problems. Can privatisation of water be a sustainable solution for ending the water scarcity in the country? Give reasons for your answer.

Related Articles